NEW ORLEANS — One of the most common friction points as the offshore wind industry sets up in the United States is its potential impact on commercial fishing.

The effects are hard to predict because there’s so little operational data from U.S. waters.

Environmental impact reports prepared for individual proposals have projected that wind farm construction and operation likely will have negative effects on commercial fishers, with the severity depending on the equipment they’re using and the species they’re pursuing. The cumulative or synergistic effects of multiple projects in the same region are expected to be greater still.

Reducing the resulting friction with the fishing industry was a workshop topic at the International Partnering Forum on April 23. One focus of conversation was the effort by the 11 coastal states from North Carolina to Maine to create a regional framework for compensating fishers for economic losses caused by offshore wind farms.

The Fisheries Mitigation Project of the Special Initiative on Offshore Wind has the standard goals of avoiding impact where possible, minimizing impacts that cannot be avoided and mitigating those impacts that occur, with financial compensation if other mitigation options are exhausted.

Kris Ohleth, director of the Special Initiative on Offshore Wind, moderated the workshop discussions.

Greg Lampman, director of offshore wind for the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, noted the current effort is a significant shift from the early days of offshore wind planning.

“Back in 2018, that was a real third rail,” he said. “No one wanted to talk about compensatory mitigation because we were not going to be harmed by offshore wind in any way, shape or form. And to suggest [otherwise] was going to be problematic for the industry.”

Vineyard Wind was the first major U.S. project to put steel in the water, and it did so with a problematic compensation plan, said Geri Edens, head of permitting and environmental affairs for Vineyard Offshore.

She said the regional approach is needed, especially in areas where multiple adjoining wind farms will span multiple states’ coastlines.

“It’s impossible for every single project in every single lease area to confine and set up these programs when fishermen are fishing across these lease areas,” she said. “The way it’s set up, it’s fraught with potential disadvantages and discrepancies between fishermen. There’s lots of opportunity for double dipping, there’s all kinds of things that could become really problematic if we have like five, six of these different individual programs set up.”

The panelists speaking in this IPF24 workshop were drawn from the offshore wind industry and government. The fishing industry was not represented.

“The fishermen are in this really awkward position where in general they’re not in favor of offshore wind and would like to see it stop,” Lampman said.

If they participate in the mitigation project, he explained, they might be seen as supporting offshore wind or be blamed for a final product the industry does not like; if they shun the process, they have no voice in shaping that final product.

Education and outreach are needed to get these vital stakeholders into the process, Lampman said.

Fishing industry representatives have gone to court repeatedly in so-far-unsuccessful attempts to halt individual projects. (See Another Federal Lawsuit Seeks to Invalidate OSW Approvals.)

In one notable instance, industry representatives quit a Rhode Island advisory board because they felt their concerns were being ignored. (See Fishermen Quit RI Coastal Board in Anger.)

Brian Hooker of the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management said the regional mitigation project has the advantage of not starting entirely from scratch.

“There are other programs that exist,” he said, such as a fisheries contingency fund in the Gulf of Mexico and fishery disaster declarations by the National Fisheries Service.

The workshop included audience questions.

Gordon Carr, executive director of the New Bedford Port Authority, asked what would happen if projects the mitigation program is based on prove inaccurate.

“What if downstream, we start realizing that the impacts are greater?” he asked. “By the time we’re realizing that, it’s really late for the commercial fishing industry, and obviously that’s sort of an existential concern, both for us and for them.”

“My response would be mostly geared towards what we have under our authorities under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act and our regulations,” Hooker said. “But I do believe we have that regulatory authority to address an unforeseen harm.”

Lampman suggested the federal government create a disaster fund, given that it is pressing for offshore wind development and regulating it.

“One of the big questions that remains is ecosystem change, and how [do] the fisheries, fish population and population dynamics change as a result of the big picture? And it’s not a number that you can really pick out of the hat right now,” he said.

Edens embraced the idea of taxpayers paying for impacts on fisheries that exceed the contracted mitigation sums, because open-ended financial commitments are difficult for developers to make. “I know that people don’t want to hear this, but these projects have to be financed. People that invest in these projects need certainty.”

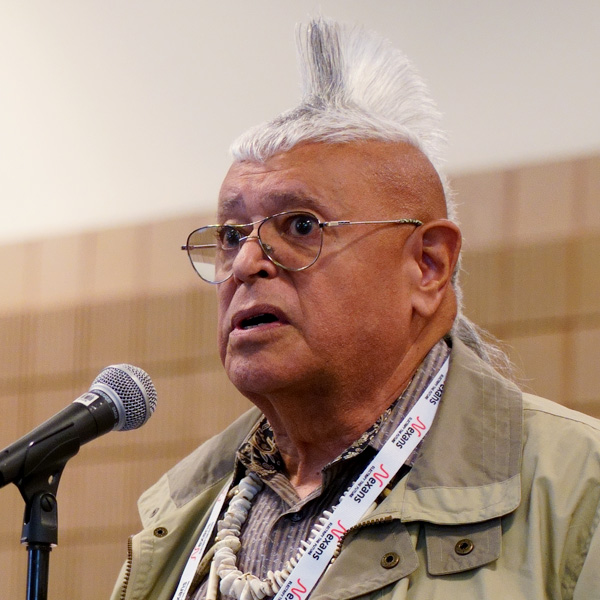

Peter Silva of Coastal Tribal Resources, an elder of New York’s Shinnecock Nation, said his concern is not so much for the commercial fishery but the wellbeing of fish and the environment in which they live.

He applauded the panelists and the entities they represent for their words and commitment but asked about all the unknowns that persist, now that the first large U.S. offshore wind farm is complete, the second is under construction and two more gear up to start construction this year.

Has boat traffic impacted commercially valuable fish in New York and New England waters? Are other species expanding their habitat into the area? Are breeding grounds affected? Are there changes in currents? Are dead zones expanding in Long Island Sound? Are water temperatures changing?

Those are excellent questions, Ohleth responded, but they are outside the expertise of panel members.

“I don’t think I’m the right person to speak the details there,” said Bryan Stockton, Ørsted Americas head of federal and regulatory affairs. “But I know that if your question is, as a determined condition of approval, do developers or government agencies in collaboration have a responsibility to continue to pursue robust monitoring, the answer is absolutely yes.”

Lampman said he, too, was unable to speak to fisheries population dynamics, but the Regional Wildlife Science Collaborative for Offshore Wind was established and funded for exactly that purpose, looking at not single projects but the aggregate impact of all offshore wind farms in the region.

Edens said Vineyard has multiple monitoring programs in place during construction that will continue through the project’s life. “So, I think we will get there, but it’s going to be a while before we have real answers to those very good questions,” she said.

“Thank you very much for your honest presentation and thoughts,” Silva said. “And hopefully the next time I’m here, if given the opportunity, I will hear [about] monitoring, and the good and the bad and the ugly of monitoring findings and corrective actions that we take.”

Additional IPF24 Coverage

Read NetZero Insider’s full coverage of the 2024 International Partnering Forum here:

Central Atlantic Region Prepares for OSW Development

Interior Announces Updated OSW Regs, Auction Schedule at IPF24

Louisiana Manufacturers Expand into Offshore Wind

Moving Offshore Wind Beyond Contract Cancellations

New York Starts Another OSW Rebound