Serving new demand from medium- and heavy-duty vehicle (MHDV) electrification will require some grid upgrades, but it could lower utility rates, Advanced Energy United said in a paper published May 6.

Impacts at the substation and feeder level will vary by where fleets of electric MHDVs might charge and how much headroom exists on the distribution system. That will require careful estimation and planning as fleets electrify, the report says.

“Greater MHDV electrification will result in greater electricity sales, increasing utility revenues,” the report says. “As long as the increased utility revenue from [electric vehicle] charging exceeds increases in utility system costs, transportation electrification will benefit all electric utility ratepayers by putting downward pressure on rates.”

That might not mean lower rates overall because other factors could drive them up, Richard Khoe, program supervisor at the California Public Utilities Commission’s Public Advocates Office, said on a webinar held by United on May 7.

His office did a similar study for California, which estimated a total of $26 billion to upgrade the distribution grid for the electrification of light-duty vehicles, MHDVs and homes, compared to a $50 billion estimate from a different report conducted for the PUC.

“We also found that the downward pressure on rates might not be achieved if any of the following things were to occur,” Khoe said. “For example, if EVs mostly charged in the evenings near peak hours, that would drive peak load up … and that would lead to higher upgrade costs.”

Using electric rates to subsidize charging excessively — or the study’s upgrade cost estimates being too low — could lead to higher rates, he added.

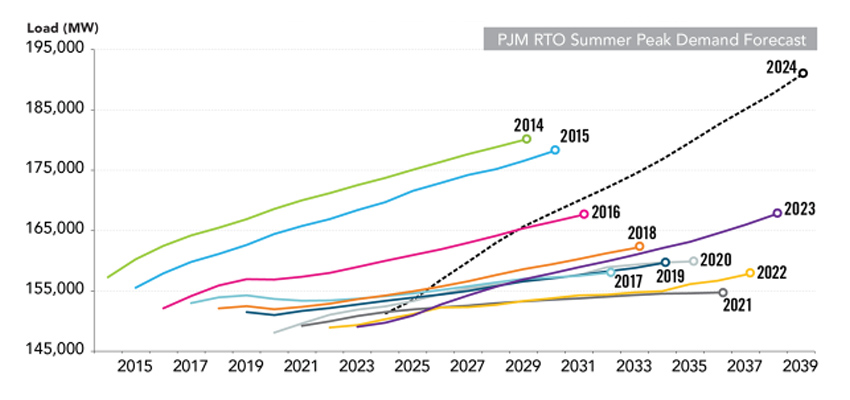

“We found that on a systemwide basis, peak loads probably are only going to increase by about 1 to 2% … by 2035,” said United report co-author Sarah Shenstone-Harris, of Synapse Energy Economics. “So not all that much. But at the feeder and substation level, the impact is much more varied.”

The main issue with MHDV electrification is that vehicles are likely to be clustered at specific sites, such as a warehouse district with panel trucks, or a bus depot, Shenstone-Harris said on the webinar. Some of those areas might have enough headroom to accommodate charging, but others will require upgrades.

“Generally, studies have found that loads of 1 to 5 MW will require a new feeder, or an upgrade, and loads of 5 to 10 MW will require a new substation or a substation upgrade,” Shenstone-Harris said. “But again, it really depends on the specifics. And as you can imagine, cost ranges also vary a lot depending on the specifics of the project, as well as lead time.”

United’s report offers four recommendations for states to get it right:

-

- require utilities to share data about capacity of the distribution grid;

- improve utility planning and regulatory processes to address barriers to electrification;

- implement programs to manage peak loads and minimize costs; and

- target certain areas for grid investment and/or MHDV adoption.

“A state or utility that doesn’t adopt these kinds of recommendations [is] surely going to be confronted with painful challenges down the road,” the New York Department of Public Service’s Zeryai Hagos said. “And this is because the four recommendations will work in unison to avoid long delays in interconnection — delays that could last for several years.”

A study in New York found that MHDV make-ready programs, which cover the upgrade costs of electrification, have a neutral to beneficial impact on rates through 2045, the report says. Benefits grew when charging was shifted to off-peak hours.

MHDVs can also serve as batteries in vehicle-to-grid services, contributing to grid stability and supporting the integration of renewable energy sources. Possessing larger batteries than standard cars, MHDVs can charge with more renewable energy when it is producing a surplus and can offer bigger discharges when the grid is stressed.

EVs cost more upfront than standard models, but they benefit from major fuel and maintenance savings over their lifetime. An electric delivery truck can save 34% compared to a diesel model over its lifetime, while an electric bus could save 24%.

“Electric vehicles have fewer moving parts and simpler drivetrains compared to internal combustion engines, leading to substantially lower maintenance needs,” the report says. “Plus, with EVs’ regenerative braking technology, certain pieces of braking equipment need to be replaced less frequently.”