New Jersey has enacted a package of new construction incentives worth up to $5.25 per square foot for new residential and nonresidential construction, in line with the state’s commitment to adopt an electrification program to install electric space heating and cooling systems in 400,000 homes by December 2030.

The New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (BPU), which approved the incentive plan April 30 in a 4-0 vote, will start providing the incentives in coming months. The program is designed to streamline the application process for new construction and set up a long-term goal of “transforming the new construction market in N.J. to one in which most new buildings will have ‘net zero’ energy usage,” according to a BPU release.

BPU President Christine Guhl-Sadovy said the plan, known as the New Construction Program, “improves standards and achieves greater energy efficiency to benefit the environment, residents and businesses in New Jersey.“

It aims to do so by creating a single point of entry into the program, eliminating market gaps and optimizing program process flow, the agency says. Builders and developers can seek incentives through three pathways — “bundled,” “streamlined” and “high performance” — for which participation is determined by the elements of the proposed project and its effectiveness in cutting emissions.

The basic incentive plan offers a payment of between $0.25 and $2.50 per square foot of construction, to which a bonus can be added for reducing greenhouse gases. A project also can receive a bonus of $1.50 per square foot if the project reduces carbon emissions by 3 tons. And it could receive an “enhanced incentive” of up to an additional $1.25 per square foot if it creates affordable housing, is a nonresidential project in an urban opportunity zone or is an industrial “high-energy intensity building.”

Persuading Consumers

The program is part of Gov. Phil Murphy’s effort to achieve the building electrification goals he set out in a February 2023 order. Aside from the electrification of 400,000 homes, the order calls for electric space heating and cooling systems to be installed in 20,000 commercial properties and for the state to ensure that 10% of all low- to moderate-income properties are electrification-ready by 2030.

To that end, Murphy (D) has created a Clean Buildings Working Group to plot the transition and a task force to study how to mitigate the impact on the gas sector, as well as a portfolio of incentive programs. State officials say they are not forcing a shift to gas — not “mandating anyone give up their gas stove,” as one BPU official put it — but want to do so by encouraging consumers to make the move with incentives.

However, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection in December 2022 held off enacting a rule that would have banned the installation of new commercial-size fossil fuel boilers after Jan. 1, 2025, after protests from business and fuel groups. (See NJ BPU Outlines $150M Building Decarbonization Plan.)

A key element of New Jersey’s strategy, as in other states, is to improve the efficiency of existing buildings, cutting energy waste and heat leakage. Yet a panel at the Montclair State University Clean and Sustainable Energy Summit on May 2 on “Energy Efficiency Innovation for Equitable Decarbonization” showed that strategy is not easy.

Speakers representing different utilities said factors such as supply chain delays and cost increases, lack of resident awareness of programs, landlord reluctance to invest in their buildings and the “culture shock” experienced by consumers confronted with an unfamiliar program asking them to make a dramatic shift have presented challenges and helped prevent the programs from gaining greater traction.

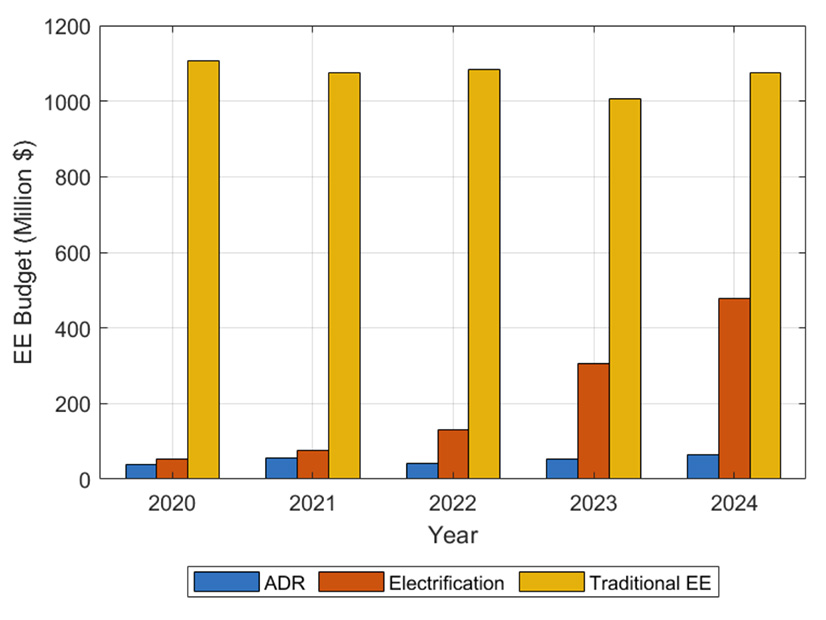

New Jersey is at the start of a “new dawn” of energy efficiency that began with the 2018 passage of the Clean Energy Act, which gave utilities the responsibility for implementing energy efficiency programs, Anne-Marie Peracchio, managing director of marketing and energy efficiency for New Jersey Natural Gas, said at the conference. The law set goals of a 2% annual reduction in electricity sales and a 0.75% reduction in gas use.

In July 2021, the state enacted a three-year energy efficiency program — known as a Triennium — and last year, it approved a second period, Triennium 2, running from 2025 to 2027 with funding for demand-response programs, voluntary electrification backed by incentives for appliances and projects costs and weatherization assessment and remediation.

Building Owner Reluctance

Implementing the program has presented a series of challenges, said Sirajuddin Shaikh, senior engineer for utility Jersey Central Power & Light Co. Inflation has slowed the uptake of efficiency measures, as has customers finding the payback period is longer, he said.

Supply chain problems emerged in 2021 and continue, especially for orders of mechanical equipment, for which deliveries can be delayed by 15 to 30 weeks, he said.

“Not all customers are able to wait that long,” he said.

Some potential projects never advance because building owners don’t want to be bothered with the paperwork required to take part in an efficiency program or are not comfortable with the ongoing evaluation of the impact of the project, which is needed to verify its effectiveness, Shaikh said.

In addition, as time moves on, “low-hanging fruit” projects that immediately improve efficiency — such as installing energy-efficient lighting systems — are completed. And some building owners are reluctant to undertake the kind of “deep-retrofit” measures that are left, and that require greater investment and a longer payback period, he said.

Another challenge is that the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect the market, with many people still working from home, resulting in low office occupancy rates.

“Building owners are looking at the buildings and saying, ‘Hey, if the offices are not occupied, what’s my motivation to invest money in my building to make it more energy efficient?’” Shaikh said. Some building owners also don’t see the benefit of investing in energy efficiency because it’s the tenant — and not the owner — who benefits from the cost reduction, he said.

“There is a constant tension going on,” he said. “Whether you’re talking about commercial property or multifamily property, most of the tenants are responsible for paying the utility bill.”

Consumer Education

Candyce Rountree, manager of residential energy efficiency for Pepco Holdings, said the company has a “huge challenge with customer awareness” of its portfolio of energy efficiency programs, with customers often unaware that programs existed or what they are for.

“A lot of customers were a little bit confused about, you know, why a utility company would be incentivizing customers to use less of their products,” she said.

A key solution adopted by Pepco was to mount an aggressive outreach program, she said.

“We’ve offered community workshops, we’ve engaged community outreach businesses, we’ve had targeted marketing campaigns and partnerships with local organizations,” she said. “And all that was crucial for increasing awareness and encouraging participation in our energy efficiency programs.”

The company also needed to overcome the fallout from the increase in interest rates, she said. Pre-pandemic, the company offered ratepayers zero-interest loans to buy energy-efficient products, but the rise in interest rates pushed up the cost of running the programs because the utility had to “buy down those interest rates,” she said.

Tim Fagan, manager of planning and evaluation for Public Service Electric & Gas, said promoting the adoption of heat pumps in New Jersey poses challenges. For one, convincing customers in the North of heat pump capabilities is tougher than in Southern states, where the winters are milder and the heat pump “down there runs more or less just like an air conditioner.”

New Jersey’s relative energy costs also pose a challenge, he said. From a financial standpoint, switching from an oil or propane heater to an electric heat pump “generally speaking is positive for the customer,” he said.

“However, when a customer switches from natural gas to a high-efficiency heat pump, generally speaking, it’s not,” he said. To compensate, the utility emphasizes a broader, “whole-home approach,” and that helps shift the equation, he said.

“We’re going to look at the whole house,” he said. “Insulate it, air-seal it, make sure that heat transfer slows down. And therefore, when you put that heat pump in, perhaps now you can turn the overall kind of equation from negative to positive, or at least bring it down to make it a little bit more palatable for the customer.”