Modernized regulations for offshore wind energy development announced in April have been published in the Federal Register and will take effect July 15.

Federal regulators say the streamlining of a regulatory regime that dates back 15 years — to well before the current wave of offshore wind development began — will save time and money as the public-private drive to site dozens of gigawatts of emissions-free generation in the ocean moves forward. (See Interior Announces Updated OSW Regs, Auction Schedule at IPF24.)

Promised benefits such as greater flexibility, improved review processes, elimination of unneeded requirements, auction reforms and clarified oversight were welcome news to an industry struggling against economic and logistic headwinds in the United States even as it enjoys unprecedented financial and policy support.

NetZero Insider asked three people closely involved in U.S. offshore wind development — a developer’s attorney, an advocate and a former federal regulator — what pieces of the Renewable Energy Modernization Rule they think will be most impactful and what else they think could have been included.

Industry Veteran

Robin Main co-chairs the Environmental and Energy Group at law firm Hinckley Allen after decades practicing that field of law.

She represented developers of the nation’s first offshore wind project — Block Island Wind Farm in Rhode Island — through a lengthy and complicated permitting process.

She subsequently represented three of the eight offshore wind projects that so far have received Bureau of Ocean Energy Management approval — South Fork Wind, Revolution Wind and Sunrise Wind.

Main said the updated rules seem a bit random in some ways, addressing some issues and not others, but the updates are important and meaningful.

“We made big steps forward with the so-called modernization rules. They were needed,” she said.

Foremost, the operational life of a project is extended beyond 25 years, and the starting point for that time frame is full commercial operation, rather than first turbine spinning.

“It’s needed because of the investments being made, the viability of the power purchase agreements, and the fact that these projects are meant to endure and certainly have an operational life beyond 25 years or so. So I was very happy to see that,” Main said.

Also important, she said, is new flexibility on the construction and operations plan (COP) — not every design change will require a COP revision.

“Because every time you made a change you had to send in a modified COP, then you had to send it to the states as well. So there was always this additional time in the permitting process that COP revisions were taking.”

Changes that Main still would like to see include better coordination among the many regulatory entities that weigh in on offshore wind development.

“I’d love BOEM to consider presumptive approvals, at least for certain aspects of projects, whether it’s cable corridors or something along those lines where developers can go in and know, ‘OK, if I meet this set of criteria or use this particular area, then it’s going to be presumptively approved,’” she said.

New York has achieved some of this type of streamlining, Main said, and Massachusetts is trying to do as well.

The new rule is a significant update, but there has been a continual evolution of the old rule as regulators added staff dedicated to offshore wind and as those people gained experience, Main said.

She saw that firsthand as she progressed from Block Island to South Fork to Revolution and Sunrise.

“And frankly, I see from a boots-on-the-ground perspective that really qualified people now want to go into that government service. They’re turned on by the fact that, you know, they’re working in energy, and whether it’s offshore wind, battery [storage] or otherwise, that this is a new frontier, and it’s much more attractive.”

Advocating for Wind

Kelt Wilska, the offshore wind director for the Environmental League of Massachusetts, also is a regional leader for New England for Offshore Wind.

As an advocate for a robust buildout of the emissions-free power source, he said he was happy to see the final version of the Modernization Rule.

“It’s good for the industry, because you’re streamlining regulations, you’re clarifying things that’s going to make the development process faster, and in turn, that’s going to be a good thing for the environment and for our climate,” Wilska said.

No single aspect of the changes jumps out at him. It’s more the entirety of the changes and the benefits they will bring to the industry.

“I think when you take all of these things together, they really add up into something special,” Wilska said.

He said he also likes the community engagement BOEM fostered while drawing up the revisions and hopes it will continue.

“What I want to see generally from my zoomed-out perspective as a coalition facilitator is that BOEM continues to have these frequent opportunities for public comment and participation,” Wilska said. “I think that it’s appreciated from us as advocates, and I’ve seen it appreciated by them because we can submit very technical expertise that is reflective of our very broad coalition of folks from the science space, from labor, from community organizations, from businesses. That’s all very meaningful.”

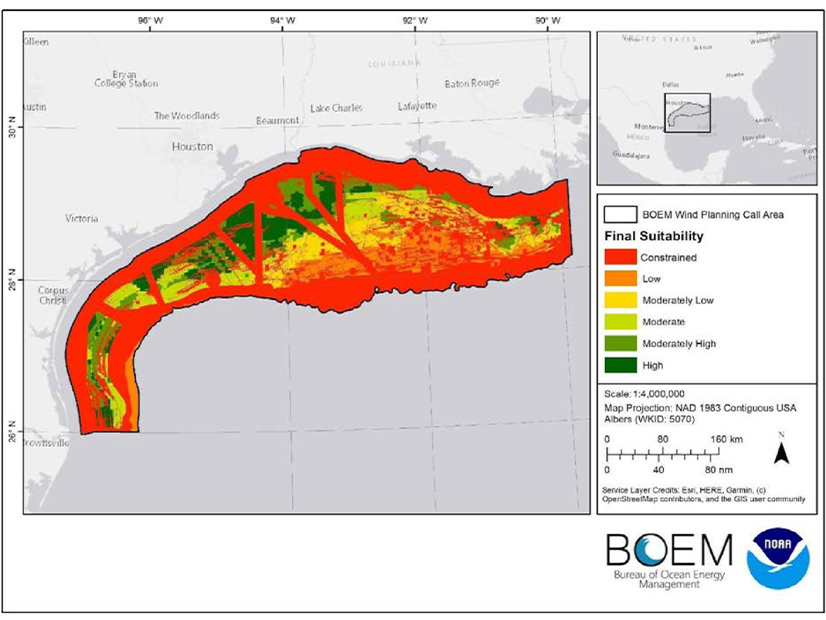

He’s aware not everyone feels their voice is being heard, perhaps none more so than commercial fishers. But the fishing industry is being heard, he said, noting that BOEM in 2023 removed Lobster Management Area 1 from the wind energy area it was drawing up in the Gulf of Maine.

Offshore wind will be a tough sell for some groups, but Wilska said he will not give up: “As long as I’m in this position, I’m going to keep trying to reach out to people and bring them into the conversation and see what we can do and what we can find common ground on.”

He acknowledges the new Modernization Rule may become moot if a certain wind turbine hater is elected president.

“Of course, I have concerns about what a potential future Trump administration could do to the regulations set forth by this current administration. There’s a lot that a future administration could do to put a hold on a lot of the progress we’ve been seeing.”

Multiple Roles

Josh Kaplowitz has been in offshore wind for a dozen years and has seen regulatory evolution from several perspectives.

He started off with gigs for the Department of Energy and what was then the American Wind Energy Association, then worked five years in the Office of Solicitor at the Department of Interior as counsel to BOEM; was commercial counsel at General Electric; was vice president for offshore wind at the American Clean Power Association; and now is senior counsel at law firm Locke Lord, focusing on offshore wind and other renewable energy.

“So I’ve seen some things,” Kaplowitz said.

The new rule is an important update, he said. It replaces a regulatory structure Interior created in the mid- to late 2000s, when there was no U.S. offshore wind industry.

“They were furiously writing regulations, and the only model they had for offshore energy was oil and gas. And they did their best at the time to try to adapt these oil and gas regulations to this brand-new industry, or at least completely new in the United States and still pretty new in Europe,” Kaplowitz said.

“And it quickly became clear that it didn’t always work. But actually, I will say the fact that the industry has progressed this far with rules that have essentially been unchanged for 15 years is a testament to how they didn’t do a terrible job on the front end, and they at least had the foresight to build in some flexibility through departures. They had a departure mechanism that allowed for the particularly egregious flaws in the rule to be sort of corrected on a case-by-case basis.”

Kaplowitz said he sees some missed opportunities in the revision, such as greater certainty in permitting timelines or more structure in leasing schedules.

“Overall, it was necessary, and it should be really helpful. Is it sufficient to make sure that the industry can accelerate and endure through changes in administration? I don’t think so. But that’s kind of the nature of the beast. What they did was very good.”

The operational lifespan is a key change, in Kaplowitz’s view.

Not only does the clock not start until full commercial operation, the default lifespan also is extended from 25 to 35 years, and BOEM has discretion to go even longer.

“I think that will make a positive difference in terms of financeability of these projects. And the design life of these of these technologies has improved over time, certainly over the 15 years that BOEM’s been regulating it,” he said.

And the revised decommissioning bond requirement — it can be spread over the project lifespan rather than posted up front — is huge, Kaplowitz said. “That is probably the most economically measurable, economically impactful provision.”