A recent study from the U.S. Department of Energy finds that managed charging ― that is, shifting the time electric vehicles charge to off-peak hours ― could be critical to controlling the costs of building charging networks and local electric distribution systems needed to power them.

DOE’s Multi-state Transportation Electrification Impact Study looks at EV adoption and infrastructure buildout in California, Illinois, New York, Oklahoma and Pennsylvania, as accelerated by EPA’s recent rules aimed at slashing carbon dioxide emissions from light-, medium- and heavy-duty vehicles. (See Automakers Get More Time, Flexibility in EPA’s Final Vehicle GHG Rule and EPA Issues Final Standards on Heavy-duty Truck Emissions.)

By 2032, those rules could put an extra 3.9 million plug-in EVs of all classes on the road in those states ― bringing the cross-state total to 20 million EVs ― along with 2.3 million additional EV chargers. But, the study finds, managed charging could halve the number of new substations needed and cut additional grid investments by $700 million.

The study provides even more granular figures, based on a unique “bottom-up” methodology developed by Kevala, a grid analysis firm, which partnered with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory on the project. Drilling down to the parcel level, researchers were able to model the kinds of chargers that might be installed on individual feeders between 2027 and 2032.

Again, managed charging could cut the number of extra feeder lines needed ― to carry power from substations to end users ― from 125 to 75, and the number of additional service transformers needed from 30,000 to 21,000.

As defined in the study, managed charging not only shifts the time when charging occurs, but also minimizes its speed “such that the session is completed just prior to [an EV’s] departure from that location.”

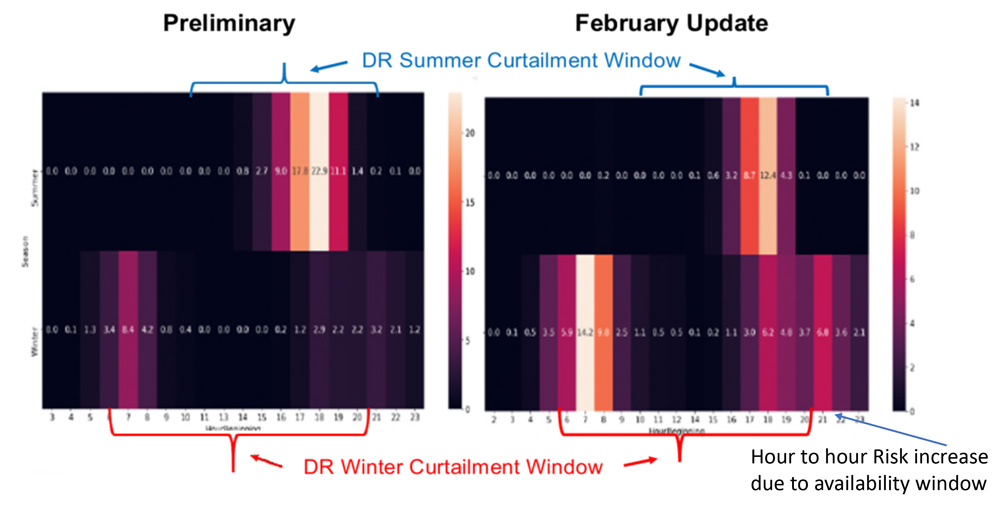

The study also notes that managed charging programs are best suited to home and commercial depot locations, where EVs are parked on a regular schedule and therefore “are considered most likely to have margins for adjusting charging speed without negatively impacting vehicle availability.”

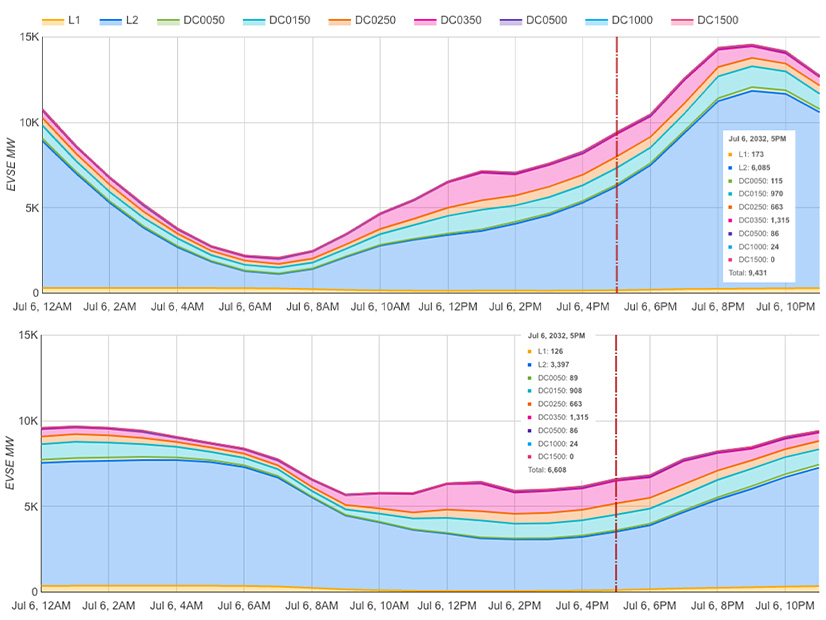

The resulting reductions in peak demand could be significant. Rather than demand spiking in the late afternoon or early evening, when EV owners arrive home and plug in their cars to recharge, managed charging could keep demand curves relatively flat, with some variation throughout day.

While the study is limited only to the effects of EV power demand and managed charging on distribution systems, the flexibility provided could have even broader system benefits when combined with other distributed energy resources on a feeder, said Troy Hodges, a data science manager with Kevala.

“One last benefit of doing this at the parcel level is not only do we know which vehicles are on those feeders, but we also have … simulated the non-EV loads on the feeders,” Hodges said during a May 22 webinar on the report. “So, from there, we can start modeling a managed charging technique that is more responsive to the dynamic needs of particular equipment on the grid.”

In one model scenario incorporating non-EV loads, the study found “further distribution cost savings, particularly on high-EV-penetration feeders,” Hodges said. In one example in California, managed charging incorporating non-EV loads cut peak demand by an additional 25%, he said.

“It really drove home the value on these high-penetration EV residential areas or commercial areas with fleet depots,” Hodges said. “This type of more advanced, active control approach could really have a big impact.”

First Time, Every Time

Distribution grid planning has emerged as a vital part of EV charger installation, with lack of capacity on local systems slowing the deployment of chargers along the nation’s highways. Funded with $5 billion from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program was created to help build out a network of 500,000 direct current (DC) fast chargers on major routes by 2030, but to date has installed eight stations with a total of 33 charging ports in six states.

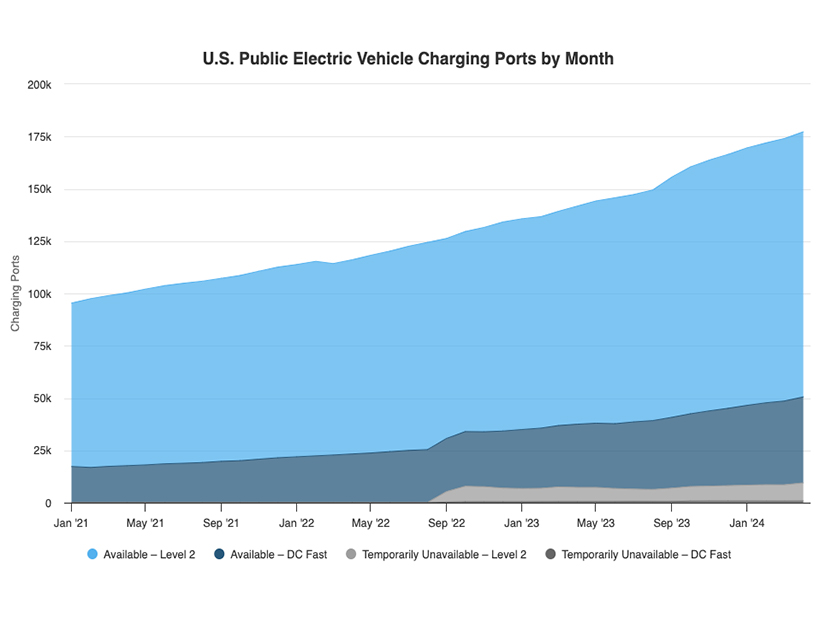

In its most recent NEVI update, the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation estimated the U.S. now has more than 183,000 public charging ports, but fewer than a quarter of those — 41,065 — are DC fast chargers. In addition, 9,472 public chargers, both Level 2 (L2) and DC fast chargers, are classified as “temporarily unavailable” — that is, not working.

Depending on the EV and capacity of the chargers (NEVI-funded chargers must be at least 150 kW), DC fast chargers can recharge a battery to 80% capacity in 20 to 60 minutes. Typically used for home or workplace charging, L2 chargers can take several hours to repower an EV.

The Multi-state Study is one of several DOE initiatives aimed at overcoming barriers to more rapid expansion of charging networks, efforts that have become increasingly urgent as the November election looms and growth in EV sales has slowed. According to Kelley Blue Book, Americans bought 268,909 EVs in the first three months of 2024, up a modest 2.6% over the first quarter of 2023, when EVs scored a 46.4% jump over the first quarter of 2022.

Along with price, consumers’ concerns about EVs’ range and charger speed and availability are the most commonly cited brakes on the wider adoption of electric vehicles, Kelley said.

DOE and the Joint Office launched the National Charging Experience (ChargeX) Consortium in August 2023 to help consumers get over those bumps. A public-private initiative, the consortium is focused on ensuring “that any driver of any EV can charge on any charger and have it work the first time, every time,” said ChargeX Director John Smart.

The group includes industry stakeholders, along with consumer advocates, academics and state government officials, who collaborate on “complex issues … that no single company can solve on their own,” Smart said during a May 23 webinar providing a progress report on the group’s efforts.

“To truly understand the customer experience, we need more metrics … that are used and measured uniformly across the industry, so that everyone’s speaking the same language, so that we’re properly measuring and therefore improving the customer experience,” Smart said.

Top priorities include developing minimum standards ― or key performance indicators (KPIs) ― that will provide the benchmarks needed to make charging more predictable and reliable.

Breaking down the KPIs

Frank Marotta Jr., assistant manager for charging network reliability at General Motors, detailed how the consortium breaks down a customer’s experience at a charger into discrete elements, each with its own KPI.

“How effective are the mapping tools drivers can be using to locate the station? How effective are they at actually getting the vehicle right up to the plug?” Marotta said.

“We have waiting probability, which is basically the probability that at least one port might be available to deliver energy when the EV arrives,” he said. “And under starting to charge, we have two KPIs … one that is meant to measure the effort required to actually start the charging session and then … the time required to actually get that session initiated.”

Another priority is communication between EVs and chargers, and chargers and the cloud, Smart said. “What is needed to allow the industry to scale, and specifically as more makes and models of chargers come to market and more makes and models of electric vehicles, how do we ensure that they all work together going forward?”

The answers will include better sharing of diagnostic data between stakeholders and improving interoperability “to efficiently verify that every charger works with every vehicle,” Smart said.

Market growth and the resulting need for interoperability and better grid planning are coming. While only a handful of NEVI projects are online now, the Joint Office has reported that 36 states have at least issued their first solicitation for chargers, and 23 have made conditional awards or agreements for more than 550 charging stations, each with four or more ports.

The Joint Office’s checklist for state planners includes early communication with utilities to prepare for the interconnection of NEVI-funded stations.

Also, consumer range anxiety could begin to taper off, with DOE reporting that 19 EV models that were on the market in 2023 could travel 300 miles or more on a charge, up 35% from 14 such models in 2022.

While noting that “everything about EVs is controversial,” Kelley expects market growth to continue, driven by the increase in available models and some price reductions. The slowdown could be a sign that EVs are becoming mainstream in some parts of the country, Kelley said. “Segment growth typically slows as volume increases.”