Maryland wants to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 60% by 2031 and have a carbon-free electricity system by 2035, which means the use of natural gas, and the need for ongoing investments in pipelines and other gas infrastructure, also should wind down, according to a People’s Counsel petition to the Public Service Commission.

Filed in February 2023, the petition asked the PSC to open a docket on the future of gas in the state, and whether gas utilities should be allowed to continue such rate-based infrastructure investments. The commission has yet to act on the petition, but on July 25, it held a daylong public hearing on whether it should open such a docket. A second session is scheduled for July 31.

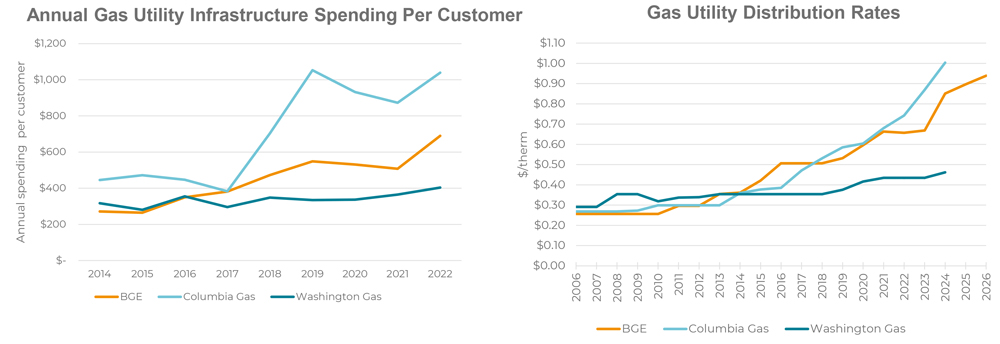

Electric heat pumps, more efficient than gas furnaces, already are eating into the gas utilities’ market, according to People’s Counsel David S. Lapp. Yet utility spending on replacing and updating existing infrastructure could total more than $700 million this year, which pencils out to close to $2 million in utility spending per day ― and rising gas utility bills.

“There’s a massive disconnect between the technology, climate policy and what’s actually going on with the state’s gas utilities,” Lapp said. Even so, investors are willing to provide capital for gas infrastructure because the commission continues to approve the utility investments and rate increases.

“We would argue that is a state subsidy to the gas utilities funded by utility customers who have no choice but to pay those rates or get off the gas system,” Lapp said. “So, in that sense, regulation is failing customers today.”

The OPC petition also raises the possibility of a gas utility “death spiral” as customers electrify their homes and drop off the system, leaving a diminishing base of customers, many of them low-income, to cover system costs through higher rates.

“As customers leave the system, rates will go up further, and then more customers will leave the system,” Lapp said. “So, this is not an economically sustainable path.”

However, Lapp stressed that the petition does not seek to shut down gas utilities; rather, it calls on the commission to open a proceeding that would consider a “wide spectrum” of pathways for these companies to plan for substantially downsized demand and capital spending.

Following Lapp’s presentation, a panel of gas company executives mostly stayed away from the topic of rate increases, arguing instead that maintaining and investing in their pipelines and other infrastructure could be critical for ensuring grid reliability even if natural gas demand does decrease.

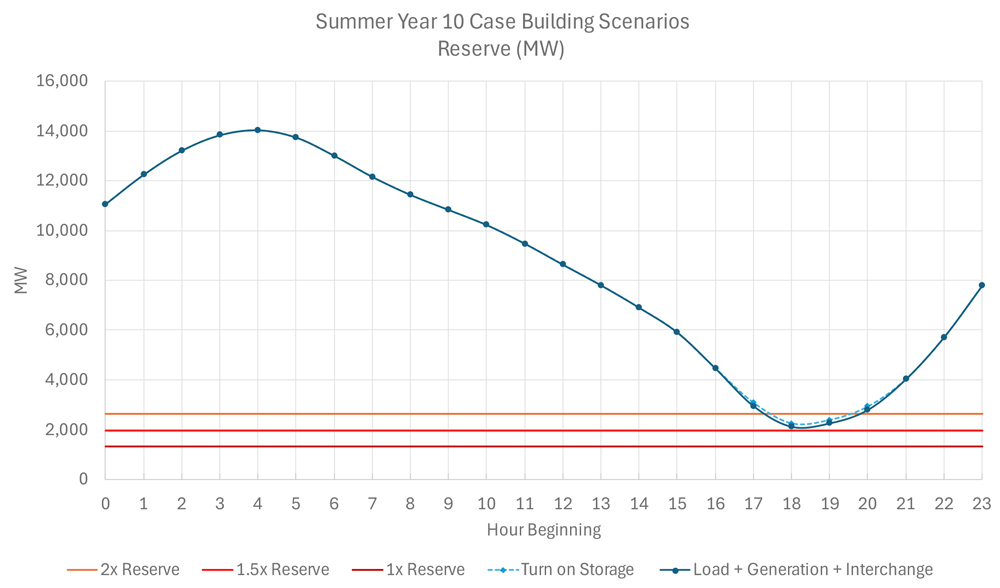

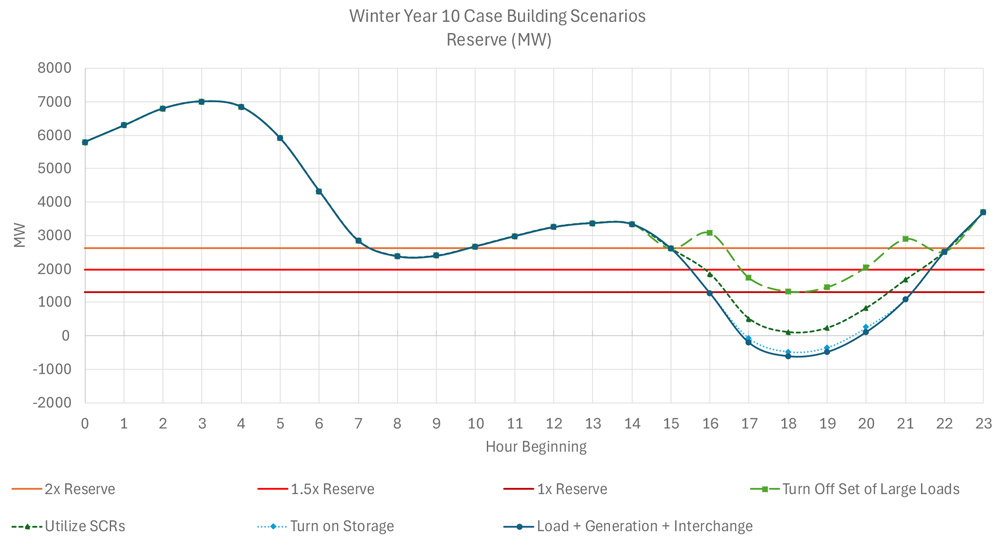

Demand reduction “doesn’t necessarily mean there would be a proportionate reduction in gas infrastructure,” said Lauren Urbanek, senior manager of decarbonization strategy at Baltimore Gas and Electric. “That’s really dependent on the geographic nature of where customers may choose to electrify and whether they would choose to electrify completely or partially, potentially maintaining gas as a backup for some of the winter peaking days.”

Upgrading gas systems also can cut down on leaks, Urbanek said, noting that BGE has cut gas leaks on its system 25% since 2015. She also stressed BGE’s support for electrification, such as a planned study on “targeted electrification.”

“This is going to help us better assess what the potential is on the BGE system of geographically targeting heat pumps, network geothermal [or] other technologies in the BGE service territory,” Urbanek said. Potential savings “could either be used to support building electrification … or be returned to gas ratepayers as well.”

Ted Gallagher, general counsel for Columbia Gas of Maryland, similarly countered that his company has increased the number of customers it serves in Western Maryland — up 9.7% since 2005 — but has cut its emissions 5.7%.

He also urged the PSC to expand any potential docket to a more holistic examination of the future of energy in the state.

“The proper scope of [any] commission proceeding … should address Maryland’s whole energy future and not just focus on the future of natural gas,” Gallagher said. “The focus should not be based upon a foregone and unsupported conclusion that natural gas should be or will be phased out in order for Maryland to achieve its GHG emission-reduction goals.”

The STRIDE Act

The debate over gas utility spending in Maryland ― and the OPC’s petition ― trace their roots to a 2013 law called the Strategic Infrastructure Development and Enhancement (STRIDE) Act (S.B. 8/H.B. 89).

Passed in the wake of the deadly 2010 explosion of a Pacific Gas and Electric natural gas pipeline in San Bruno, Calif., the bill was intended to encourage Maryland utilities to upgrade and improve the safety of their pipelines by allowing them accelerated recovery of their infrastructure investments.

Specifically, customers have for the past 10 years paid an extra surcharge on their bills so gas utilities could start to recover their infrastructure investments while improvements and upgrades were being made. The law also requires the utilities to submit STRIDE plans to the PSC every five years, as well as yearly reports on current investments.

While the law does not set any safety standards or require long-term planning, its impact on rates has been dramatic, according to the OPC. BGE’s distribution fees for natural gas went from 26 cents/therm in 2010 to 85 cents in 2024, with another jump to 96 cents in 2026 already approved by the PSC.

Distribution fees at Columbia Gas jumped more than threefold, from 30 cents/therm in 2010 to $1 in 2024, or more than three times the rate of inflation, the OPC said.

The STRIDE program is set to continue through 2043, by which time total utility spending under the program could hit $9.5 billion, in addition to another $12 billion in system investments outside STRIDE, according to a 2023 OPC report.

A bill to require utilities to use modern leak detection technology and repair pipes before replacing them (S.B. 548/H.B. 731) was introduced in the General Assembly earlier this year but did not make it out of committee in either house.

In light of the bill’s failure, views differed on whether the legislature or the PSC has the authority to make any changes to the program. Urbanek said BGE would be “supportive of some kind of working group or other forward-looking proceeding that really does relate to the future of gas. … But really, the decision is still to be made by the General Assembly about the exact pathway to follow.”

Lapp argued that the PSC has the authority, as regulators, to require the gas utilities to provide the commission with long-term plans on their infrastructure investments based on the expected decline in gas demand, and that the need to act is urgent.

“The idea that the commission has to wait for somebody else to set the policy, for the General Assembly to set the policy, ignores the critical point that right now there is a policy, and that policy is one of accelerated spending,” he said. “It is leading to massive rate increases; it is leading to investments that are highly likely to be stranded and to result in a lot of litigation going forward. That is the policy, and waiting means the inertia will just keep that going.”

‘Stop Digging’

The PSC also heard a wide range of views from environmental advocates, union representatives, county officials and Maryland residents and utility customers.

Emily Scarr, director of the consumer advocacy nonprofit Maryland PIRG Foundation, supported the OPC’s call for a docket on the future of gas, pointing to the increases in BGE and Columbia Gas distribution fees.

“When you find yourself in a hole, stop digging,” Scarr said. “We’re asking you to put the shovel down and exercise your authority to require utilities to serve the public interest by providing safe, reliable and affordable energy. We can only achieve that goal with proper planning and data-driven decisions. The cost of inaction is clear. … You can direct investments wisely in the projects that will lower energy bills.”

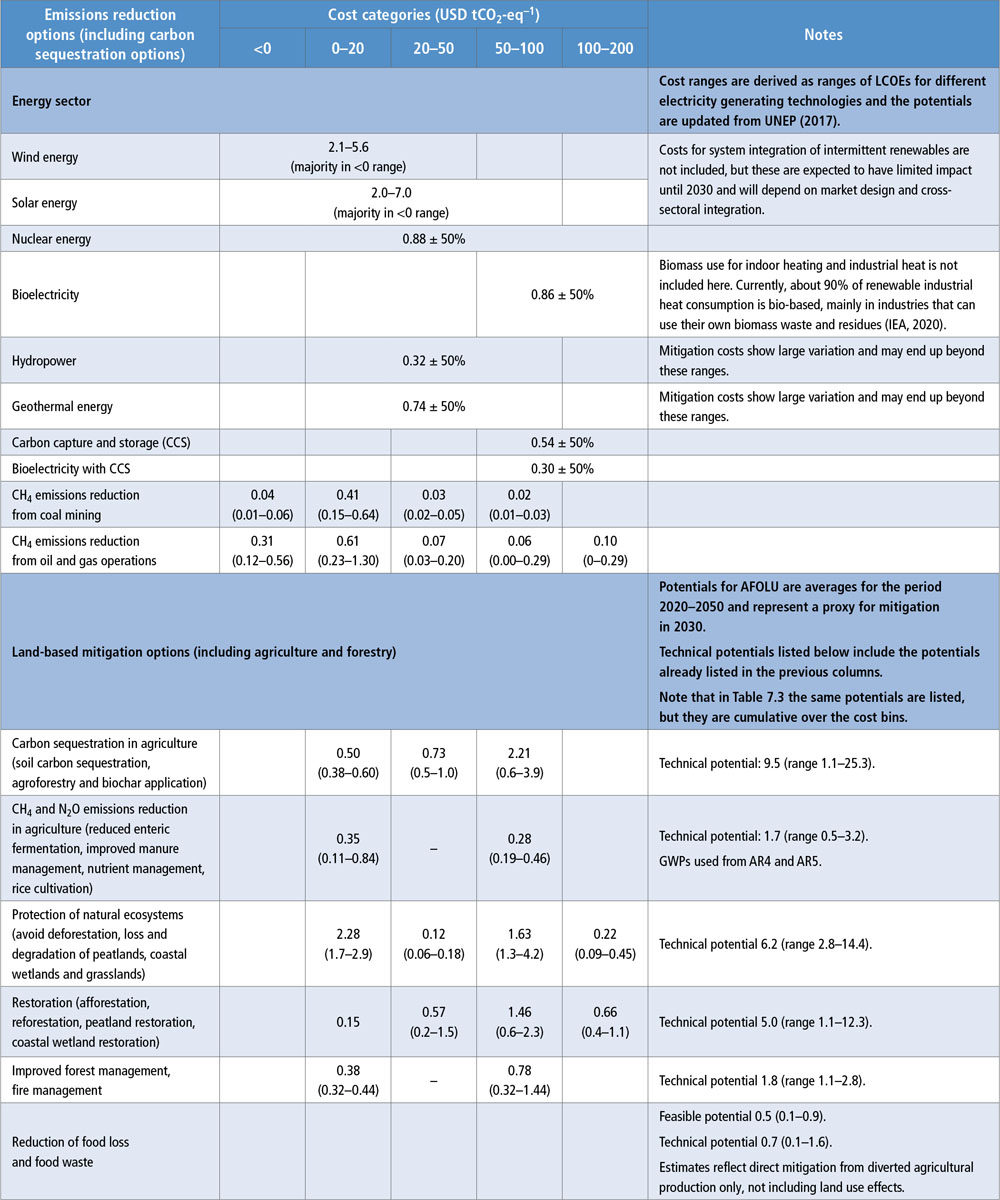

Clara Vondrich, senior policy counsel at Public Citizen, said Maryland’s “energy policy as manifested through the proceedings and decisions of this honorable commission, as well as through legislation like the STRIDE Act, are incompatible with the state’s climate goals and in fact may make them impossible to meet.”

Vondrich told the commission she lives with her 85-year-old mother, who has become a little forgetful and has lost her sense of smell. Recently, Vondrich woke up to find her mother had left the gas on overnight and had not smelled the methane.

“We’re no longer in an era where we need to take those kinds of risks,” she said.

Brian Terwilliger, a business manager for the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 410, raised the concerns of the BGE workers his union represents. BGE’s gas system is one of the oldest in the country, which makes STRIDE upgrades essential, he said.

“Just a few months ago, we dug up a wooden main just down the road here, about 20 feet of it,” he said. “Our infrastructure has generational gaps; so, we have from wood to the most up-to-date stuff for our pipes.”

But Terwilliger warned that downsizing the gas system could trigger a mass exodus of skilled workers.

“They’re thinking about where they’re going to go, how this transition is going to work, and it’s going to be extremely difficult for Baltimore Gas and Electric to retain employees,” he said. “Our ask today … is really to look at the workers at the companies and think about how we’re going to continue to keep those employees employed.”

A transition period “needs to be at the forefront of this conversation,” he said.