U.S. greenhouse gas emissions have decreased significantly over the past decade and are on track to decrease even more precipitously in the next decade, according to the Rhodium Group’s annual update of its “Taking Stock” report, issued July 23.

The organization found the country’s GHG emissions were 18% lower in 2023 than in 2005, and it estimates they will be 32 to 43% lower in 2030.

This is a marked acceleration just from 2022, the report’s authors write, but even a continuation of that would leave the U.S. short of the 50 to 52% reduction by 2030 that it committed to under the Paris Agreement in 2015. The country might not achieve a 50% reduction until the mid-2030s, the report indicates.

Under a midrange scenario, the report projects a 65% reduction in emissions from power generation through 2035, as fossil-burning generators are replaced by renewables, and a 26% reduction from transportation, as the number of internal combustion engines decreases.

But industrial sector emissions are projected to decrease only 5% through 2035, at which point it would be the largest U.S. source of GHG emissions. And emissions from the agriculture sector actually could increase slightly, according to the analysis.

Rhodium issued its first “Taking Stock” report in 2014 and has updated it annually. In announcing the 2024 update, it noted the historic confluence of factors in the past few years that has accelerated emissions reductions in the U.S., including the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which have helped spark a clean energy boom.

It is a marked change from the conclusion of the 2014 report, which incorrectly predicted GHG emissions would increase through 2020.

The report notes potential obstacles to continued progress, including the Supreme Court or the next president striking down or weakening the regulations that have been instrumental in bringing about the reductions to date.

Ironically, attempts to build a domestic clean energy manufacturing base could result in an increase of emissions; meanwhile, interconnection delays, local opposition, transmission constraints and robust growth of GDP could slow the decrease of emissions.

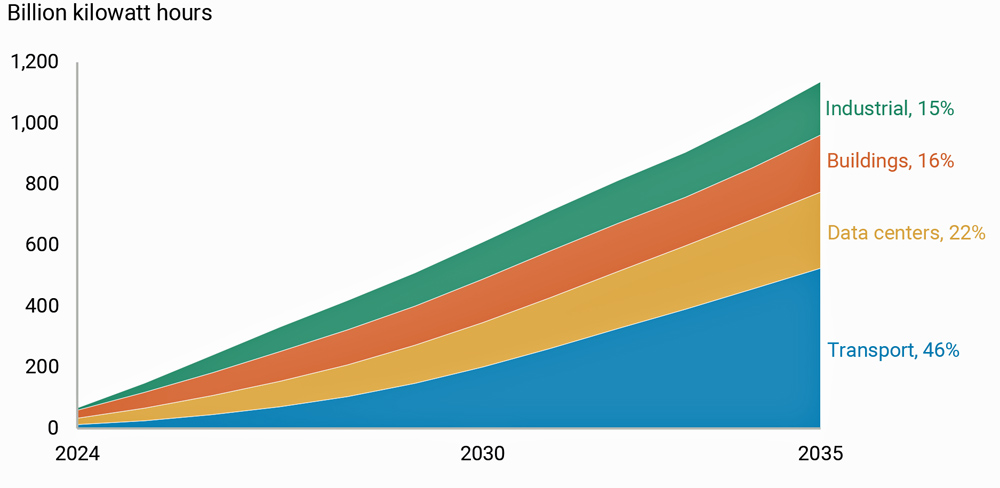

The report also flags supply chain constraints and data center demand as disruptors. Difficulty building renewables and the continued proliferation of data centers would result in 2035 power sector emissions that are substantially higher than in a scenario in which neither complicating factor existed. The report notes fossil generation retirements already are being reconsidered because of these two factors.

Because of all these variables, the report gives a range of potential outcomes under three models:

-

- a high-emissions scenario where emissions-free energy deployment is slowed by high costs for renewable technologies, low costs for fossil fuels, interconnection queue delays and supply chain constraints;

-

- a low-emissions scenario where low-cost clean energy technologies and expensive fossil fuels drive a rush of investment in emissions-free power; and

-

- a mid-emissions scenario that splits the difference.

The report anticipates a 38 to 56% reduction in U.S. GHG emissions by 2035 over 2005 levels, factoring a few trends into this projection:

-

- Zero-emissions sources such as wind, solar and nuclear could account for 62 to 88% of total generation by 2035, and coal could be nearing zero. This would yield a 42 to 83% drop from 2023 power sector emission levels.

-

- By 2035, 64 to 74% of light-duty vehicles sold could be electric, and 30 to 45% of medium- and heavy-duty vehicles sold could be zero-emitting, causing transportation sector emissions to drop 22 to 34% from 2023 levels.

-

- Emissions from oil and gas production could drop 12 to 28% below 2023 levels because of EPA regulations that limit release of methane.

-

- Regulatory changes phasing out hydrofluorocarbons could cut building emissions by 9 to 12%.

The report bases its projections for the next decade on state and federal policies in place in June 2024, which is an unstable foundation, the authors note. “The only thing that we can be certain of is that these policies will change by 2035 — probably many times over.”

States can step up and take action if the federal government will not, they add.

“What’s certain is that more policy action is needed for the U.S. to put itself on track for its 2030 commitment under the Paris Agreement and for deep decarbonization by midcentury.”