The Supreme Court’s liberal wing defended EPA’s authority to impose “beyond-the-fence-line” regulations on power plants Monday, while conservative justices provided fewer signals on their leanings during oral arguments in a challenge by the coal industry and 20 states.

The arguments focused on EPA’s authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions under the Clean Air Act and whether the Clean Power Plan (CPP), proposed by the Obama administration, was nullified in January 2021 when the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the Trump administration’s replacement, the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule.

The D.C. Circuit’s 2-1 ruling vacated the ACE rule and remanded it to EPA for further action. (See DC Circuit Rejects Trump ACE Rule.)

West Virginia Solicitor General Lindsay See | The Federalist Society

West Virginia Solicitor General Lindsay See | The Federalist SocietyWest Virginia Solicitor General Lindsay See told the court Monday that Section 111 of the Clean Air Act directed EPA to “partner with the states to regulate [emissions] on a source-specific level.” But the D.C. Circuit ruling went far beyond that, See said, violating the “major questions” doctrine — that Congress must be explicit in giving an administrative agency the power to make “decisions of vast economic and political significance.”

“Electricity generation is a pervasive and essential aspect of modern life and squarely within the states’ traditional zone” of authority, she said. “Yet EPA can now regulate in ways that cost billions of dollars, affect thousands of businesses and are designed to address an issue with worldwide effect. This is major policymaking power under any definition.”

The court agreed to consider the matter in October, consolidating four challenges and saying it would hear one hour of oral arguments (West Virginia v. EPA, 20-1530). But — perhaps reflecting the case’s potential implications beyond EPA’s authority — Chief Justice John Roberts allowed the arguments to stretch on for two hours. Observers have said a ruling that concludes EPA lacks authority to decide matters of “vast economic and political significance” could have a wide impact on administrative law.

Nothing to See Here

Justices Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor asked most of the questions during the session, with Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito leading the questioning by the conservative wing.

U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar | Justice Department

U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar | Justice DepartmentU.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar said the court should reject the challenge because EPA has no plans to resurrect the CPP. “Petitioners aren’t harmed by the status quo,” she said. EPA expects to issue a replacement Notice of Proposed Rulemaking by the end of 2022, with a final rule likely about a year later, she said.

Prelogar also contended there is no “major question” at stake. “For all their criticisms of the CPP, we know that it wouldn’t have had major consequences. The industry achieved the CPP’s emission limits a decade ahead of schedule and in the absence of any federal regulation,” she said.

But See said the D.C. Circuit’s ruling vacated both the ACE rule and the Trump administration’s repeal of the CPP.

“We’re injured by a judgment that brings back to life a rule that hurts us and it takes off the books a rule that benefits us,” she said. She added that EPA’s brief indicated “that they might enact the very same provision, and they have told you nothing different here today. … Even though nationwide, the emission levels have been largely met for the Clean Power Plan, 20 states have not met them.

“This is an area where the parties need certainty,” she added. “The states and regulated parties make decisions decades in advance.”

‘Fence Line’ Arguments

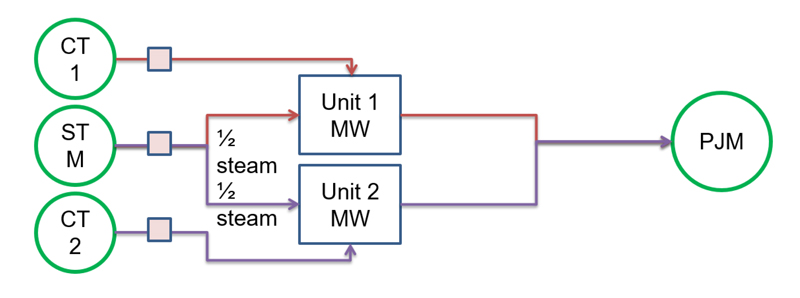

The CPP sought to cut power sector carbon emissions by 32% by 2030, compared with 2005 levels, through “generation shifting”: substituting coal-fired generation with natural gas and renewables. The challengers say that EPA’s authority to regulate power plants is limited to steps individual plants can make “inside the fence line.”

Justice Stephen Breyer | Supreme Court

Justice Stephen Breyer | Supreme CourtBut Breyer, Kagan and Sotomayor said they disagreed with that interpretation, noting that Section 111(d) empowers EPA to impose standards “for any existing source” based on limits “achievable through the application of the best system of emission reduction” that has been “adequately demonstrated.”

Breyer said he agreed that Congress did not give EPA authority to impose regulations that would change “the economic system of the United States.”

“But you want to jump from there to the idea that [regulation] has to be plant by plant,” he told See. “It’s easy for me to think of a system that they might choose that isn’t plant by plant or isn’t within the fence, but isn’t really a big deal.” For example, he said EPA could order PJM to add a carbon fee to its security-constrained economic dispatch, which selects generation in least-cost merit order.

Justice Elena Kagan | Supreme Court

Justice Elena Kagan | Supreme CourtKagan said an inside-the-fence regulation “can be very small, or it can be catastrophic.”

“There are inside-the-fence technological fixes that could drive the entire coal industry out of business tomorrow. And an outside-the-fence rule could be very small, or it could be very large,” she added. It “bears no necessary relationship to whether a rule is major in your sense of expensive, costly, destructive to the coal industry.”

See responded that the law’s requirement that EPA must use systems that lead to achievable emission reductions that are adequately demonstrated suggests Congress intended “source-specific” requirements. “They don’t make sense when EPA is regulated at a grid-wide or nationwide level,” she said.

“‘System’ is a broad word,” she acknowledged. “But Congress paired it with limits. … The D.C. Circuit’s interpretation of the statute doesn’t give EPA any place where it has to stop. The fact that it puts self-imposed handcuffs on in the Clean Power Plan does not mean it would need to do that in the next rule.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor | Supreme Court

Justice Sonia Sotomayor | Supreme CourtKagan responded: “It does give EPA a place to stop, because the statute also says you have to consider cost and you have to consider various other factors. … It very clearly says that there are other constraints that have to be considered to impose reasonable limits.”

“I agree with you if we are talking about measures that a particular source can take, because then you would be able to look at cost and make a reasoned determination,” See countered. “But if EPA is looking at the national, or grid-wide level, and if it’s dealing with an issue as massive as climate change, it’s hard to see what cost wouldn’t be justified. So that cost limit isn’t really serving as a limiting factor.”

Cooperative Federalism

Justice Clarence Thomas | Supreme Court

Justice Clarence Thomas | Supreme CourtKagan said the statute’s reference to “system” suggests that Congress intended to give EPA flexibility, “understanding that this was an area that was going to move very fast [and] has lots of technical components to it; that it wanted to give the agency flexibility to regulate as times changed, as circumstances changed, as economic impacts changed, or things that they couldn’t possibly have known at the time” changed.

West Virginia’s interpretation, she said, would undermine the notion of “cooperative federalism.”

“If the state decides, ‘This is what we want to do. … We actually think it’s less costly than some of the inside-the-fence alternatives,’ your reading essentially says, ‘Too bad.’”

Prelogar referenced a brief by utilities including Consolidated Edison, Exelon and National Grid supporting EPA’s position.

She said a system that involves carbon capture and sequestration paired with trading would allow plants to decide whether to make the carbon-capture investments to reduce emissions low enough to generate trading credits while others would find it more cost effective to buy credits.

“The system is … reducing emissions across the source category as a whole; it’s just doing so in a very cost-effective way, which I think explains why the power plants by and large are on our side in this case,” she said. “They want that kind of flexibility because this is business as usual for them.”

See said “it’s a false argument” to contend that giving EPA more options is better for states. “The Clean Power Plan set an aggressive system that said that there were options for the state, but really, there weren’t, because states couldn’t actually have other options other than generation shifting and reduced output.”

Conservatives Appear Wary of Broad Ruling

Justice Samuel Alito | Supreme Court

Justice Samuel Alito | Supreme CourtAlito made his suspicion of EPA’s power clear, telling Prelogar, “If you take the arguments about climate change seriously … so long as the costs are not absolutely crushing for the society, I don’t know why EPA can’t go even a lot further than it did in the CPP.”

But none of the conservative judges said they thought the D.C. Circuit had erred in rejecting the ACE rule. And there was little indication that they saw the case as a forum for a sweeping ruling on the major-questions doctrine.

Justice Neil Gorsuch said Prelogar “makes a strong argument that states are not harmed here because, under the current state of affairs, there is no rule in place.”

Justice Amy Coney Barrett distinguished the case from the court’s September ruling that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lacked power to order a moratorium on evictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. That case, she said, concerned whether “the CDC can regulate the landlord-tenant relationship.”

In the current case, she said, “if we’re thinking about EPA regulating greenhouse gases, well, there’s a match between the regulation and the agency’s wheelhouse, right?”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh noted the electric utilities’ argument that cap-and-trade systems are more flexible and better than command-and-control rules. “I think those are all — you know, those are solid arguments that we … need to consider.”