A new report by a research arm of the trucking industry quantifies challenges facing electrification of the sector, including the need for billions of dollars’ worth of chargers and vastly more power flowing through the grid.

Running every commercial truck on the road today with battery power instead of gasoline or diesel would consume 550 billion kWh per year, or 14% of the electricity now used in the United States, the American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI) said.

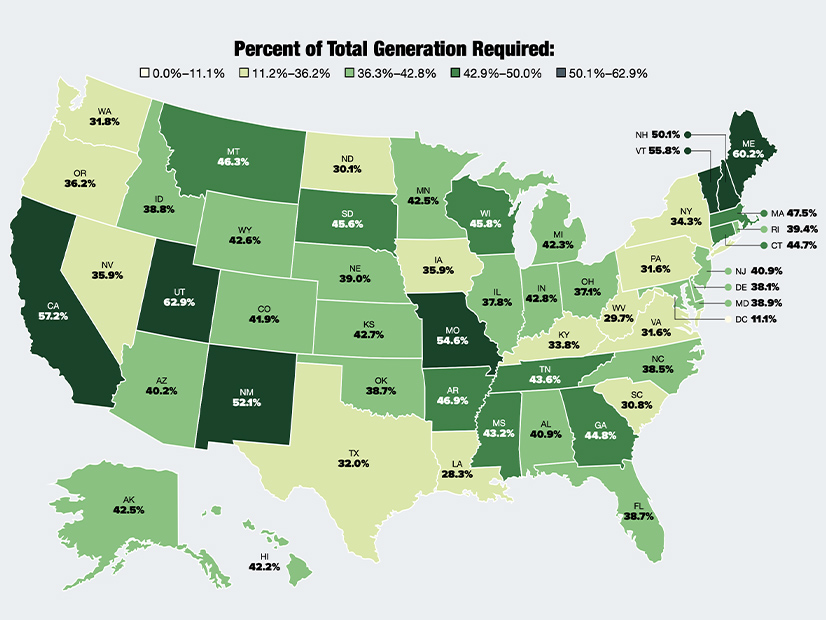

If most other U.S. vehicles also were electrified, as many climate-protection roadmaps call for, the demand would increase to 40% of present electrical consumption nationwide and as much as 60% in some states, the report concluded.

This growth would come as electrical demand from other sectors would be greatly expanding, at the same time that many power generators transition from polluting but reliable fossil fuel to clean but variable renewable energy.

On Dec. 5, ATRI released “Charging Infrastructure Challenges for the U.S. Electric Vehicle Fleet,” the second of two reports on zero-emissions trucking.

The new report flags several potential sticking points on the path to widespread use of electric trucks, including shortage of lithium for batteries and space for all the new truck charging stations that will be needed.

The report does not explicitly oppose wide-scale electrification of trucks, but in a news release announcing its publication, a member of ATRI’s board of directors suggests that the zero-emission mandates some states are pushing for heavy-duty vehicles cannot become an electrification mandate.

“The market will require a variety of decarbonization solutions and other powertrain technologies alongside battery electric,” wrote Srikanth Padmanabhan, president of the engine business of truck engine manufacturer Cummins.

ATRI is a nonprofit affiliate of the American Trucking Associations, which calls itself the largest trade organization representing the U.S. trucking industry.

Yellow Flags

The issues raised in the ATRI report primarily involve the heaviest trucks in long-haul service, rather than lighter trucks or those operating in a smaller radius. And they are offered with caveats, as it is impossible to quantify the impact of future technology and hard to generalize heavy-duty EV charging needs thanks to such factors as air temperature, battery state of charge, charging rate, age of battery and frequency of braking.

The yellow flags it raises boil down to scale: Staggering amounts of raw materials, electricity, time and real estate would be needed to build and charge electric versions of the 12 million fossil fuel-powered commercial trucks on the road today.

Simultaneous electrification of light-duty trucks and cars would ratchet up those challenges.

The report on the trucking industry’s challenges with electrification splits into three points of focus: Electrical supply and demand, electrical vehicle battery production, and logistical challenges to charging trucks.

It makes the following observations:

The interstate trucking industry must traverse 49 states and thousands of local jurisdictions. There are nearly 3,000 electrical utilities and more than 60 grid balancing authorities. This creates a patchwork of policies, prices, regulations and capacity.

The percentage of each state’s present power generation output that would be needed to charge batteries if every vehicle registered in that state were electric. | American Transportation Research Institute

Roughly 3.93 trillion kWh of electricity was consumed in the U.S. in 2021. Had every internal-combustion vehicle in the nation been battery-powered, and if the study’s parameters are correct, those vehicles would have consumed an additional 1.59 trillion kWh. The 3 million heavy-duty tractor-trailers alone would have consumed 417 billion kWh.

Much of the infrastructure that would be called upon to generate and transmit this additional electricity dates to the mid- to late 20th century, during the last great period of expanded U.S. power consumption. Some of it is near the end of its useful life, and some is outdated. But with sufficient investment in generation and transmission, the necessary amount of power could become available.

Variable electric rates may be necessary to balance supply and demand in a given market, but they may hinder industry adoption of battery-electric trucks.

The existing shortage of truck parking will need to be addressed, but at much greater cost, because electric trucks need not only a place to park but an available charger at the parking spot.

Federal rules mandate truckers drive no more than 11 out of 24 hours, and an ATRI study found drivers already spend an average of 56 minutes a day looking for a place to park and go off duty. With truckers not allowed to be at the wheel more than half the day, it is economically unfeasible to have them sitting for hours charging or waiting to charge while on duty.

Battery-electric trucks weigh several tons more than their diesel-powered counterparts, meaning more trucks will be needed to carry the same amount of freight and remain under the 80,000-pound limit.

It takes a few minutes to pump 300 gallons of diesel into a heavy-duty internal combustion engine truck, enough to travel 1,800 miles. It would take more than four hours for a 210 KW charger to bring a 1,500-KWh battery to optimum 80% charge, and that would take a fully loaded tractor-trailer only about 500 miles.

To make widespread long-haul truck electrification possible, many hundreds of thousands of fast chargers are needed nationwide, at a cost that can exceed $100,000 each. (California estimates a need for 157,000 new chargers for medium- and heavy-duty vehicles within its borders by 2030, as it works toward all new trucks being zero-emissions by 2045.)

The authors said potential solutions include megawatt-level charging stations and wireless chargers embedded in roadways, both of which are currently in development; modular batteries that can be swapped out at a truck stop; and, in remote locations, off-grid charging.

The report also flagged thorny non-technical issues certain to arise, such as who will pay for installation and maintenance of the chargers, and noted that whatever cost increases truckers bear will trickle down to consumers of the goods they are hauling.