One of the early drivers in the effort to site floating power generation off the U.S. coast outlined a plan last week to continue its early work, enlarging its economy and shrinking its carbon footprint in the process.

The Maine Offshore Wind Roadmap is the result of 18 months’ work by 96 committee members studying the concept from every angle.

Much of the roadmap boils down to core concepts: gathering data; collaborating on plans to use the data; communicating those plans; minimizing adverse impacts and maximizing benefits of those plans; and ensuring those benefits are shared equitably.

Bringing those concepts to fruition is where the challenges and disagreements will crop up, and the roadmap seeks to prevent as many of them as possible.

Speaking to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Floating Offshore Wind Shot Summit on Thursday, after her Energy Office released the roadmap, Gov. Janet Mills cited all the groundwork Maine has done to prepare for the effort, including placement of the first test turbine in U.S. waters.

“Maine has the tremendous potential to become a global leader in offshore wind, and that means more good paying jobs, cleaner energy and a healthier environment,” she said. “We’ve already started the work to get us here as well.”

With its strong and sustained winds, the Gulf of Maine is considered one of the best potential U.S. sources of offshore wind energy. But it is too deep for wind turbines with rigid sea-floor foundations, so development there will rely on floating turbines, a concept still in development.

Meanwhile, a large part of Maine’s economy is linked to its oceanfront and fishing industry, which are anxious to avoid harm from placement of wind power arrays. In response, Mills in 2021 signed into law a 10-year moratorium on offshore wind development in state waters, pushing the nascent industry farther out into federal waters.

Outsized Plans

Large states such as California, New York and New Jersey have been one-upping each other with high-megawatt offshore wind goals, but small states such as Maine and Rhode Island (whose combined population is one-eighth New York’s) are also contributing to the growth of the sector.

The first few fixed-base offshore wind turbines in the U.S., in Rhode Island waters, have yielded empirical knowledge that can be incorporated into future projects, and Maine has been researching floating offshore wind (FOSW) technology for more than a decade.

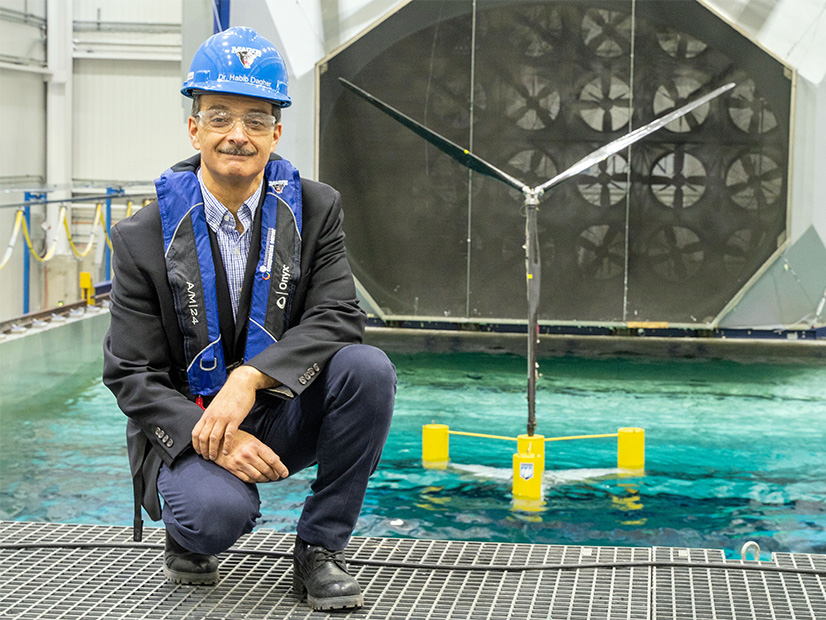

The University of Maine’s Advanced Structures & Composite Center has developed VolturnUS, a semisubmersible concrete hull for FOSW applications, and hopes to commercialize it. The center’s executive director, Habib Dagher, told the FOSW summit Thursday that it shares technology with bridge construction and can be manufactured in local communities. A decade ago, the university placed a 1:8 scale test turbine off the coast at Castine.

In 2024 the university and its partners plan to anchor a single 11-MW floating turbine near Monhegan Island. This will pave the way for a planned research array of 10 to 12 FOSW turbines, with a capacity of up to 144 MW, farther out to sea. Maine hopes to gain U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management approval in 2023 for the project. (See BOEM Continues Planning Process for Maine OSW.)

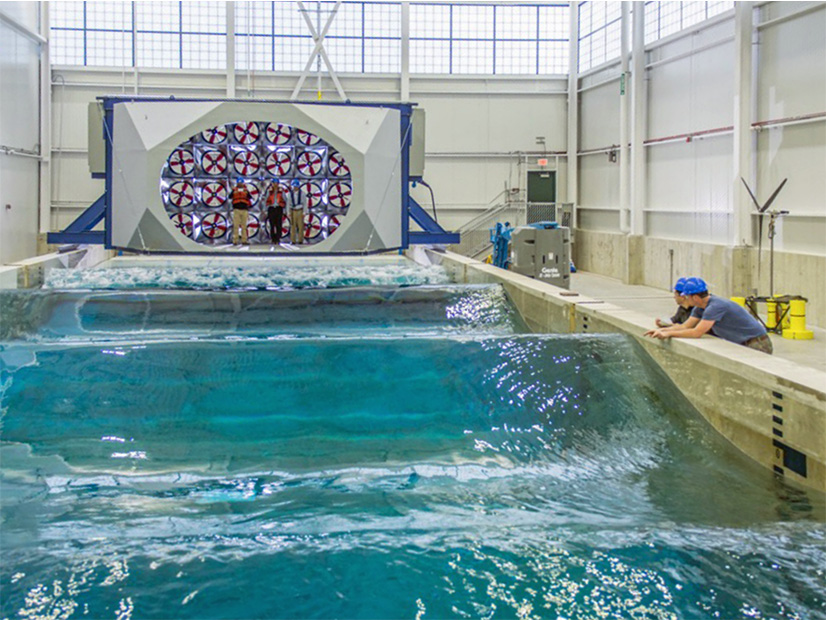

The university also has reported advances in floating light detection and ranging technology, synthetic mooring lines and 3D printer fabrication of components. It has built a wind-and-wave test basin, expanded its FOSW engineering team to 45 people and added graduate student concentrations in offshore wind.

Maine is known for harsh winters, and its residents are more dependent on heating oil than any other state. The state’s decarbonization efforts and Mills’ goal of 100% clean energy by 2040 are expected to double the state’s power demand.

Against this backdrop, the state considers FOSW a source of both new energy and economic stimulus: Nearly 80 Maine firms already are engaged in or are poised to enter the offshore wind industry, and 117 occupations would be involved to some degree in a buildout, the roadmap states.

Objectives and Strategies

The roadmap and the supporting technical reports are posted on the Maine Offshore Wind Initiative website. The roadmap breaks out five broad objectives and suggests several strategies for achieving each:

- boost offshore wind supply chain, infrastructure and workforce investments by creating opportunity for Maine businesses; investing in port and manufacturing infrastructure; attracting workforce; ensuring workforce opportunity and inclusivity; and developing export opportunities for businesses and research institutions.

- harness renewable energy to control costs and fight climate change by establishing a FOSW procurement and coordinating it regionally for cost effectiveness; pursuing regional transmission strategies; ensuring a stable and predictable investment environment; and advocating for federal leasing mechanisms that support Maine’s goals.

- advance Maine-based innovation to compete nationally and globally in offshore wind by continuing development of FOSW demonstration projects; commercializing the state’s R&D capabilities; establishing an in-state FOSW innovation hub; leveraging and expanding in-state capabilities in artificial intelligence, data science and robotics; and researching complementary technology such as energy storage and clean fuels.

- support Maine’s seafood industries and coastal communities by seeking engagement and integrating technical feedback from fishers and residents; promoting open research and data-gathering; learning from information yielded by research turbines; seeking to avoid or minimize conflicts by prioritizing development outside key lobster and fishing areas; designing wind farms to ensure safe navigation; and promoting fair and equitable benefits.

- protect the environment, wildlife and fisheries ecosystem in the Gulf of Maine by collecting high-quality data in cooperation with fishers, scientists and others; proactively reducing conflicts and minimizing impacts while facilitating timely permitting; strengthening Maine’s policy framework, including through the review authority conferred by the federal Coastal Zone Management Act; enhancing collaboration with other states in the gulf; continuing state funding and pursuing federal funding; facilitating open engagement and integration of technical advice; and promoting and advancing new technologies, then allowing for their integration into planning.