Assuring consumers that the government is not “coming to take your gas stove,” New Jersey’s Board of Public Utilities (BPU) opened a two-day conference Tuesday into the contentious issue of how to dramatically reduce the use of natural gas and promote alternatives in pursuit of cutting carbon emissions.

Representatives of government, environmental groups, ratepayer advocates and utilities mapped out scenarios, challenges and potential pitfalls on how to manage the transition away from gas while protecting ratepayers and overburdened communities.

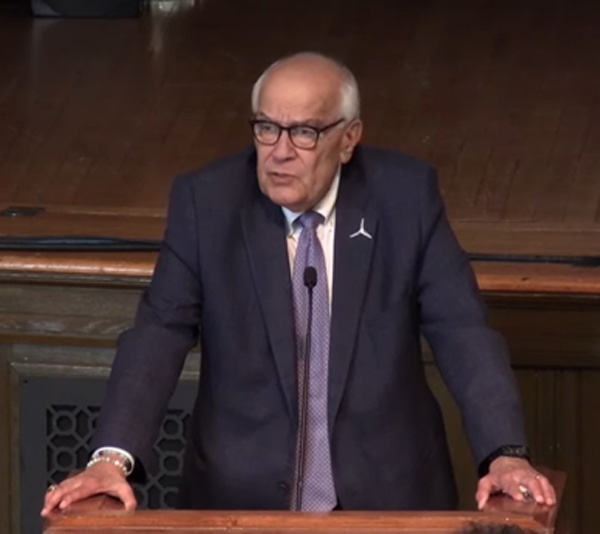

BPU President Joseph L. Fiordaliso began by dismissing what he sees as widely circulated misinformation that the state planned to mandate the use of electricity for heating, hot water and other appliances.

“Natural gas is not going anywhere anytime soon,” Fiordaliso said. State officials say a transition away from gas will be adopted voluntarily by consumers.

That switch will be difficult, complicated and unpredictable, and require extensive planning and investment, speakers said. Key to success will be balancing support for the declining natural gas sector and its users, while boosting the capacity of clean energy to handle the influx of former gas users, speakers said.

“We’re talking about a fundamental transformation of two important energy systems in the state in a relatively short amount of time,” said Bob Brabston, the BPU’s executive director, near the end of a 90-minute panel Tuesday morning on the cost impact and challenges of the shift.

“What does that mean for us as a state from an economic competitive standpoint? What does it mean to the businesses that operate here? And what are some of the things that we as policymakers should be thinking about as we talk about some of this stuff?”

‘Flat’ Building Emissions

The BPU convened the conference, which ran Tuesday and Wednesday, after Gov. Phil Murphy (D) signed an executive order requiring the agency to solicit stakeholder input and draft recommendations by August 2024 on how to shrink the natural gas sector. The state is seeking by 2030 to cut greenhouse gas emissions to 50% below 2006 levels.

State policy does not mandate a shift to electrify building water and heat systems, but a series of policies introduced by the Murphy administration heavily promote the shift, including rules approved by the BPU on July 26 that would create a series of “startup” building electrification programs backed by incentives. (See NJ BPU Backs Building Decarbonization Plan Despite Opposition.)

A separate executive order signed by Murphy calls on the state to electrify 400,000 dwelling units and 20,000 commercial spaces or public facilities by 2030.

Opponents of the plans, including business groups and fossil fuel interests, say electrification is expensive and the state’s strategy is heavy handed and doesn’t take into account alternative fuels. Meanwhile, some environmental groups say the state is electrifying too slowly.

Eric Miller, New Jersey energy policy director at the Natural Resources Defense Council, speaking on the same panel as Brabston, said the need for a solid strategy to cut emissions from natural gas use in buildings can be seen in the history of the energy generation and building sectors, which are the second- and third-largest generators of carbon emissions. While emissions from energy generation have been about halved in the past two decades, building emissions — which account for 26% of state emissions — “are about flat,” because of the lack of a policy, he said.

The solution is a Clean Heat Standard, under which the state sets a steadily increasing goal for the percentage of clean energy used by buildings, he said. Such an initiative would be flexible enough to “allow a broad range of technologies” to replace fossil fuels, he said.

Abe Silverman, former BPU general counsel who now runs a clean energy policy program at Columbia University, echoed Miller’s call for a standard, which he described as “bringing in a competitive, technology-agnostic standard for the natural gas sector.”

“That has really profound implications for how we drive investment in the sector and how we think about things going forward,” Silverman said. “When we see this in other states, we largely see this as negotiated political settlements, where you establish the benchmarks upfront, and then you use the competitive market to achieve those standards.”

Adopting such a system likely would trigger “a very difficult, contentious discussion” over the levels at which the standard is set, he said. Other thorny issues include what entities and institutions are covered by the standard, which fuels are considered clean and who will ensure compliance, he said.

Even more complicated is how to assess the “cost effectiveness” of the strategy, he said.

“We’re talking about switching people off of the natural gas system to electrification, or otherwise decarbonizing the natural gas they’re using,” he said. “You have to think about both the costs of moving customers off the gas system onto the electric system, that’s one set of costs. But then you also have to think about the cost of maintaining the natural gas system.”

Planning Future Electricity Demand

A key issue as customers leave the gas sector is whether the electricity sector has the capacity to handle the increase with clean energy rather than electricity created with fossil fuels, said Michael A. Schmid, vice president for asset management and planning at PSE&G.

“We need to be talking with our RTOs. We need to be looking at how they’re doing their planning, what they’re estimating load forecast to be compared to what the utilities are estimating currently,” he said. One example of the challenge, he said, is how to plan for the rise in electric heating, which at some point — likely 20 years or so from now — will mean the winter electricity peak will exceed the summer peak. That planning task will be further complicated by the unpredictability of the rise in electric vehicles, which PSEG expects to reach about 800,000 vehicles in New Jersey in 10 years, he added.

Silverman said utilities that serve gas and electricity customers will lose a gas customer but add an electricity customer. But utilities that serve only gas customers, or only electric customers, will see a different impact, he said.

Maintaining the natural gas distribution system will be key to big gas users, such as industrial customers, Schmid said. Utilities will continue to improve the gas system and ensure it doesn’t harm the environment, such as through methane leaks, he said.

“How do we balance out the cost of the of the gas distribution system to the costs that are going to come in on the electric system?” he asked. As utilities like PSEG continue to invest in both sides, “we have to sit there and say: Are we ready for the future?”

Customer Impact

Utilities also will have to carefully manage the effects on customers, Silverman said. He cited a section of the natural gas grid that — from an “operational perspective” and for financial reasons — should be shut down even though there are gas customers in the area that don’t want to shift to electricity.

“How do we reach a consensus as a society about shutting down that little piece of grid because there are cost savings?” he asked.

David S. Lapp, of People’s Counsel in Maryland, which advocates for ratepayer interests, said it’s important to consider the impact of the shift away from gas falls heavily on low- and moderate-income consumers.

Lapp, speaking on a panel Tuesday afternoon about ratepayer costs of the energy transition, said a study by his office of the impact in Maryland found that initially, some customers would switch away from gas. Then, as their departure pushed up gas rates because the user base was smaller, that encouraged even more users to flee rising gas prices.

“So the customers who are … capable of leaving the system will,” he said. “So, then we will have people who can’t get off the gas system, whether it’s because they’re low-income, they can’t afford switching over the appliances or they’re renters, and they don’t have that ability.”

“What we saw is really a risk of rapidly spiraling, increased gas rates for customers,” he said. One solution, he said, is to slow the pace of infrastructure spending on the gas side, to “mitigate the possibility of stranded cost.”