The U.S. Southeast may have grabbed a major share of private investment in electric vehicle and battery manufacturing, but it is well behind the rest of the country in EVs actually on the road, according to a new report from the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy (SACE).

Based on announcements through the first half of the year, the region ― which includes Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, the Carolinas and Tennessee ― accounts for 40% of all new investments in EV-related manufacturing and 35% of the jobs those projects will create, according to the report, compiled by Atlas Public Policy.

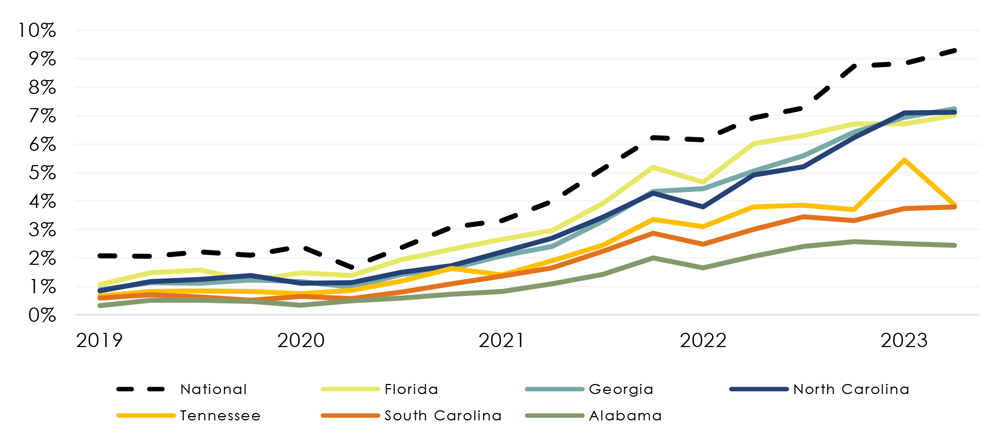

Yet, light-duty EV sales in the Southeast lie well below the national average, which is now inching up toward 10% of all new vehicle sales. Figures for the Southeast range from EVs accounting for 7% of new car sales in Florida and Georgia, down to about 2.5% in Alabama.

But that seemingly upside-down market could turn out to be a plus for transportation electrification in the region in the long term, said Stan Cross, SACE’s electric transportation program director.

“There are some states and some regions that are electrifying transportation motivated by and driven by policy: clean energy policy; climate policy,” Cross said during a launch webinar for the report on Thursday. In the Southeast, “it’s really an economic development mechanism that’s driving the market,” which could produce a slower but more deeply rooted transition, he said.

“If we start to see more charging stations, more EVs owned, more equitable accessibility across the region because those products are being made here and because those companies that are moving here are beginning to amass political sway, then that could potentially be a much more durable transition over time,” Cross said.

The Southeast could also be a strong market for the U.S. and foreign automakers seeking to challenge Tesla’s tight hold on 50% of new vehicle sales, he said. The automakers locating or expanding their manufacturing plants in the region “are a lot of those legacy automakers. It’s Honda; it’s Volkswagen; it’s Volvo, GM [and] Ford,” Cross said. “As those carmakers really step up their EV game, there’s a lot of additional opportunity [for sales] here in the Southeast … because those are the brands that consumers already trust, already have an affinity for.”

Ripe for EV Adoption

Another reason the region could be ripe for EV adoption is that relatively little fossil fuel production or refining is located there, Cross said.

“The Southeast doesn’t have any skin in the oil game,” he said. “As a result, when consumers go to the gas pump to fill up their cars … only about 23 cents of every dollar spent at the pump stays in the Southeast.”

With EVs, however, “about 71 cents of every dollar spent on locally generated electricity stays in the Southeast,” Cross said. SACE estimates that if all cars, trucks and other vehicles across the Southeast were electrified, “the region would get a $60 billion boost to the economy annually.”

While behind national figures, EV sales in the region are growing, from a cumulative total of 312,316 in the second quarter of 2022 to 469,602 this year, a 50.4% increase year over year, the report says.

Other topline figures in the report reflect the push-pull of policy and economic development in the Southeast’s EV market. Georgia leads the region in investments and jobs announced. Rivian is putting up $5 billion for a plant that could turn out 400,000 EVs per year and create up to 7,500 jobs. Hyundai is working on two EV battery plants in the state, one with LG Energy Solutions and one with SK On, with a total investment of $8.3 billion, creating up to 6,500 jobs.

But job creation is uneven across the region ― and still speculative, based on the estimates companies have announced. SACE is tracking announcements for 65,242 EV manufacturing jobs in the Southeast. Georgia leads with 27,817 potential jobs announced versus a scant 314 in Florida.

Three-quarters of all public funding for transportation electrification in the Southeast is going toward school bus and public transit electrification, with just under a quarter going toward charger deployment. The Southeast averages $3.84 per capita in public spending on vehicle electrification, well below the national average of $13.81.

A Slow Energy Transition

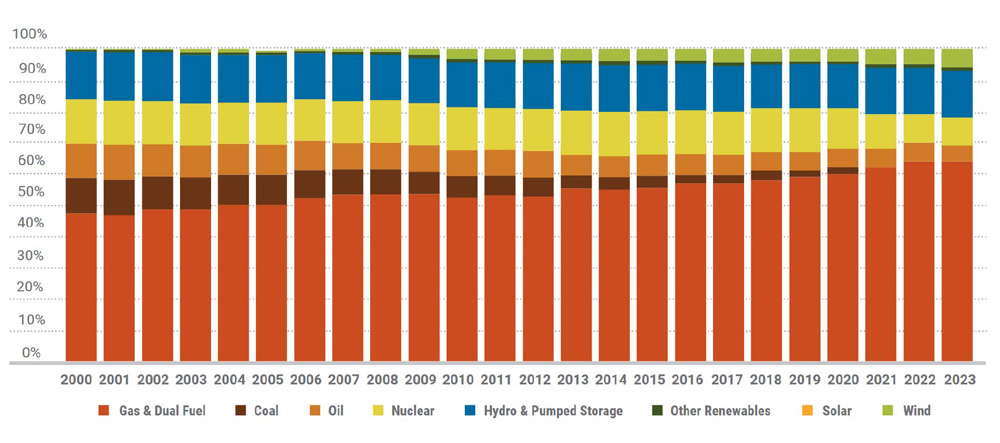

Transportation electrification in the Southeast is following a similar pattern as the region’s adoption of renewable energy has been bottom-line and market driven and, to a great extent, utility controlled. Southern investor-owned utilities held off on committing to clean energy until the cost per kilowatt-hour for solar or wind was competitive with or below the cost of fossil fuels and could be included in their rate base.

IOUs have also been a major force in slowing the development of residential rooftop markets in some states in the Southeast. For example, the North Carolina Utilities Commission recently approved a proposal from Duke Energy to establish a minimum monthly bill for residential rooftop solar owners and slash compensation to solar customers for the excess power they put on the grid.

For the EV market, IOUs are “crucial enablers of transportation electrification by being the primary supplier of energy, managing the electrical grid and investing in all or parts of electrical infrastructure that serves EV charging,” the report says.

But here, again, the Southeast lags behind the rest of the nation. Through June 2023, IOUs across the U.S. received regulatory approvals for $5.8 billion in transportation electrification investments, with approvals pending for another $1.5 billion, the SACE report says.

Approved investments in the Southeast came in at $394 million, or 7% of the national total. Only $6 million of that figure was approved for programs targeting deployment of EV chargers in low-income or other underserved communities, well below the national average.

Investments approved in individual states also varied widely. Florida IOUs are at the top of the list, putting $278.2 million into EV infrastructure, and South Carolina is at the bottom, with $8.8 million.

Florida also leads the region in charging ports deployed, with 1,843 DC fast chargers and 6,080 Level 2 chargers.

To date, most Southeast states have used money from the 2016 Volkswagen settlement ― paid after the automaker admitted to cheating on figures for vehicle emissions ― as a source of public funding for EV chargers, the report says. But SACE sees a major opportunity for EV charger deployment in the $680 million in federal funds that the region is slated to receive from the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program, established by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

The NEVI funds are initially targeted at putting DCFCs every 50 miles on interstate and major state highways.

The Policy Landscape

EV market growth faces other obstacles in the Southeast in the form of state policies that make it harder and more expensive for consumers to buy and own EVs.

Additional registration fees for EVs ― intended to compensate states for lost gasoline taxes used to maintain highways ― are now in effect in 32 states, according to a recent analysis in Money. But Georgia and Alabama have the second and third highest in the nation, $211 and $203, respectively, behind Washington state, which charges $225.

The regional average for such fees in the Southeast is $161 versus a national average of $126, according to SACE.

Cross sees the problem not as one caused by EVs, but rather by a gas tax system that itself is breaking down as all vehicles become more fuel efficient. “Many states are looking at how to transition from a gas tax to a tax on vehicle miles traveled as a way to deal with this issue, which is only going to get worse, regardless of whether electric vehicles are purchased or not,” he said in a separate interview with NetZero Insider.

The Southeast has a mixed record on laws that limit or prohibit the direct sales and servicing of EVs, another critical issue for EV market growth across the country. At issue is the sales model used by Tesla and other new EV manufacturers, selling directly to consumers, versus the legacy model of auto sales through dealerships, which is codified in law.

Florida, Mississippi and Tennessee allow direct sales; Alabama and South Carolina do not, while Georgia and North Carolina limit direct sales to one automaker, Tesla.

As with gas taxes, Cross sees attempts to limit direct sales as a counterproductive response to fundamental changes in the market ― in this case, the evolving business models and trends in consumer choice and buying habits. Direct sales are not a threat to the longstanding relations between automakers and dealerships, he said.

“Nobody’s arguing that [legacy dealerships] should not be respected,” he said. But for EV companies “to stand up nationwide dealerships is ridiculous. It’s not financially feasible, and it’s not what consumers want. … I mean, it’s difficult to find any other commodity that we purchase the same way we purchased [it] 50 years ago.”