The industrialized nations of the G20 piled up a record $1.4 trillion in subsidies for fossil fuels in 2022, driven in large part by consumer subsidies to soften the impact of the energy crisis triggered by Russia’s war in Ukraine, according to a new report from the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD).

Such subsidies come in the form of price supports or caps on gas prices, as well as tax cuts or other government actions to lower heating or gasoline costs, Tara Laan, a senior associate at IISD and lead author of the report, said during a Wednesday webinar.

“It’s understandable that during a crisis, governments need to intervene to assist their citizens,” she said. “But what we know is that fossil fuel subsidies are an extremely inefficient way to assist the poor and to provide sort of social welfare, and this is simply because those who use the most fuel often harness the most benefits.

“Why should the amount of help you get from the government be directly proportional to the amount of fossil fuels you use? What we recommend countries do is remove these subsidies and use the savings to provide targeted welfare to those who need it.”

Other key findings of the report include:

-

- Government-owned or -controlled companies invested $322 billion in investments in fossil fuel infrastructure in 2022, “and it’s only going to increase,” Laan said. “We know that national oil companies are doubling down [on investments] because of the massive profits they made in 2022.”

- G20 governments made commitments to provide $265 billion in subsidies for renewable energy between June 2020 and June 2023. That comes out to about $88 billion per year, or less than one-tenth of the 2022 fossil fuel subsidies, and Laan said, “This is commitments, not annual spending.”

- If all the G20 nations implemented a tax on carbon dioxide — proposed at $75/ton for high-income countries and $25/ton for lower-income countries — the tax could raise $1 trillion per year, “a vast amount of money that could be used for other purposes,” Laan said.

A carbon tax provides governments a way to make businesses pay for the hard-to-value “externalities” of fossil fuel consumption, such as climate change, other air pollution and traffic congestion, said Nate Vernon, an economist with the International Monetary Fund.

Such “corrective taxation” can result in “these externalities only occurring when the benefit to consumers exceeds the full cost of consumption, which improves the allocation of resources across the economy, raises revenues and results in the economically efficient level of externalities,” Vernon said.

Combining a carbon tax with a phaseout of fossil fuel subsidies could add up to $2.4 trillion per year to be diverted to a range of social welfare and clean energy initiatives, the report said.

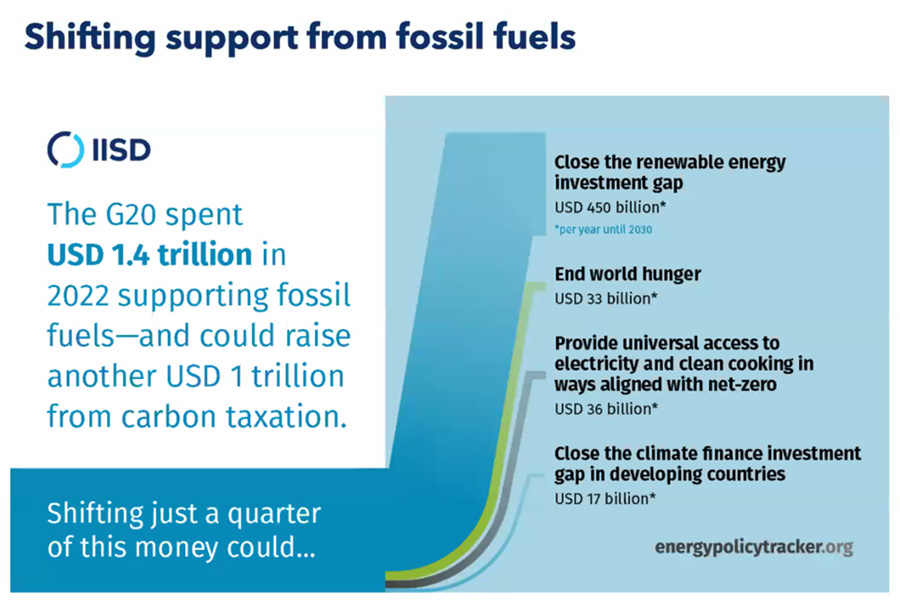

Just 25% of that total could provide $33 billion per year to end world hunger, $36 billion to provide universal access to electricity and clean cooking technologies, $17 billion for clean energy investments in developing countries and $450 billion to boost renewable energy generation, the report says.

Renewable Energy Investment Gaps

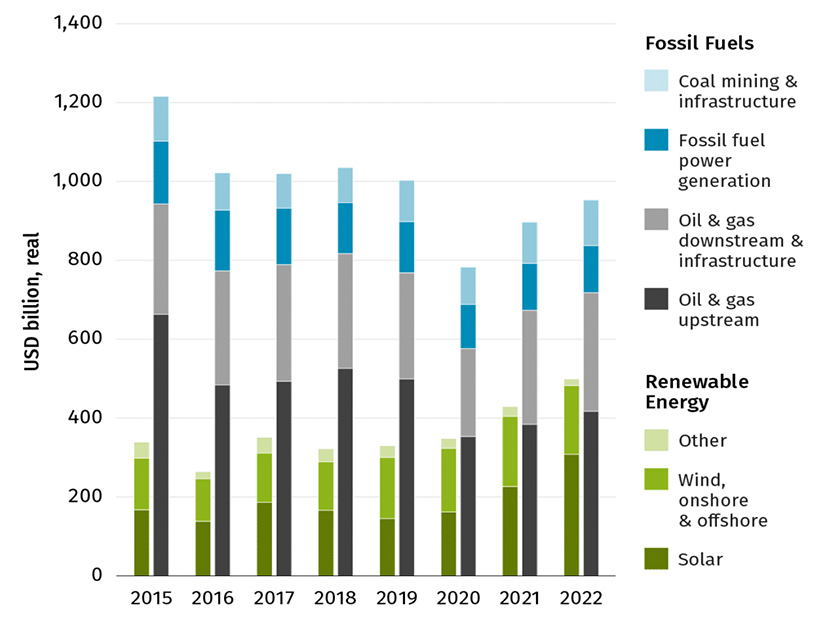

Investment trends in renewable energy also raise concerns on a global level, said Diala Hawila, program officer at the International Renewable Energy Agency. Private and public investment in renewables worldwide hit half a trillion dollars in 2022, versus $440 billion in fossil fuel investments in the G20 alone, she said.

But, Hawila said, “If we look again, at the global investments in renewables, we see more and more concentration not only in developed countries, but also in developed technologies. So, solar PV, onshore and offshore wind are almost accounting for 97% of investments. Overall, we are relying more on private investments to drive the energy transition, but private investments only go to countries with reliable markets.”

Progress on the energy transition is primarily in the power sector “because those are the mature technologies, and only in developed markets,” she said. “So, we are leaving a large chunk of the globe outside the energy transition.”

Per capita figures reveal the enormous gap between clean energy investments in the northern and southern hemispheres, Hawila said. In 2015, per capita investments in renewables in North America were 23 times higher than per capita investments in sub-Saharan Africa, she said. As of 2021, the North American figure had risen to 57 times greater than sub-Saharan Africa.

Further, Hawila said, the figures on renewable energy investment focus solely on assets and do not include “the government support that goes into creating enabling environments … for example, investing in infrastructure like grids and investing in R&D.” More than triple the current level of renewable energy investments will be needed.

“A lot of the money that is now going into subsidizing fossil fuels or into the fossil fuel industry will be needed to be channeled into [those] enabling environments,” she said.

Commitment vs. Action

The release of the IISD report appears to be strategically timed in advance of the G20 Summit in India on Sept. 9-10.

Representing the world’s largest economies, the G20, or Group of 20, was formed in 1999 to provide an international forum for economic cooperation. While sessions initially were attended by finance ministers, the recession of 2008-09 resulted in the forum being “upgraded” to high-level meetings of heads of state and government.

The group’s efforts to phase out subsidies for fossil fuels began in 2009, when members made a commitment to phase out “inefficient” subsidies, but without setting a deadline. In 2016, the smaller G7 — including Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, the U.S. and the European Union — set a 2025 deadline for the subsidy phaseout, with progress reports due in 2023.

Unfortunately, these and other international commitments on climate change have rarely led to substantive action, Laan said.

“Reform has to be made domestically,” she said. “It has to be about regulations and policies put in place by leaders in their home countries to actually implement these decisions, and that’s exactly what we’re lacking at the moment on fossil fuels.”

Exact figures on fossil fuel subsidies in the U.S. are elusive. A recent article from Reuters provided a range of $10 billion to $50 billion per year, while Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) cited a figure of $20 billion per year at a Senate Budget Committee hearing in May.

At the same time, fossil fuel giants like BP, Shell and Exxon are walking back previous commitments to cut emissions and invest in renewables, as they rake in record profits, according to an article in Grist. BP, for example, has downgraded a commitment to cut emissions 35% by 2030 to 20 to 30%.

President Joe Biden’s proposed 2024 budget included measures to scrap fossil fuel subsidies, which almost certainly will not be included in any final deal in September. On the upside, the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022 has put the U.S. way ahead of all other G20 countries on investments in renewables.

Canada Delivers

In July, Canada became the first G7 nation to issue federal guidelines for a phaseout of fossil fuel subsidies, with specific definitions of what kinds of subsidies would and would not be considered “inefficient.” To earn an exemption from the phaseout, subsidies must meet one of six criteria, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions, supporting clean or renewable energy or providing essential energy services to remote, off-grid communities.

Subsidies also will be allowed for the development of emission-abating technologies such as carbon capture and storage.

The guidelines are backed up with “a fairly exhaustive set of definitions … to eliminate the risk of these exemption criteria being used [to allow] for support outside the spirit and intent of the framework,” said Matthew Watkinson, director of regulatory analysis at Canada’s Department of Environment and Climate Change.

However, Watkinson said, the guidelines are designed to provide for an evolution in the understanding of net zero, which “is fraught with a lot of uncertainty. When you’re putting something out there now, it’s difficult to close the door completely on technologies that are still largely unknown or where there are still question marks.”

The guidelines also include “a clear statement of intent to periodically review and ensure that we are maintaining alignment with technologies as they emerge and government priorities as they emerge,” he said.

Whether Canada will serve as a spur for other G20 nations remains to be seen. Laan would like the G20 to go further, either removing the world “inefficient” from the phaseout language or more narrowly limiting exemptions to only allow for “energy subsidies for the poor,” she said.

Another big step would be for the group to set a deadline as the G7 has, she said.

The September G20 summit in India is being watched closely as any climate action or lack of it certainly will affect the already mixed expectations for the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) to be held in early December in the United Arab Emirates, a major oil producer.

Along with efforts to phase out fossil fuel subsidies, the G20 also may make decisions “on new areas of concern like supply chains, like essential critical minerals,” said Aarti Khosla, director of Climate Trends, a consulting firm in India. “Trying to just simply understand how much G20 countries that are talking about climate change are also supporting on the other hand the production and consumption of fossil fuels … is something that is going to give us a clearer idea of how climate action is being understood across the world.”