For the world to have any hope of limiting climate change to 1.5 degrees Celsius, well-off countries around the globe must stop burning coal by 2030 and cut emissions economywide to net zero no later than 2040, according to the United Nations’ Accelerated Climate Action Agenda.

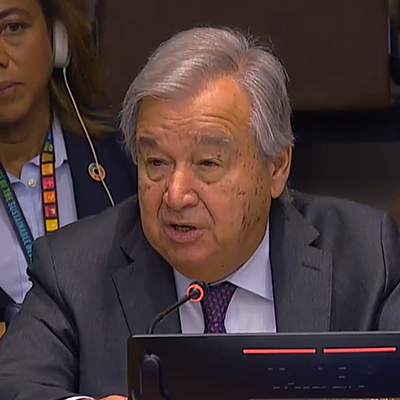

Those aggressive goals were the centerpiece of the opening plenary of the UN Climate Ambition Summit in New York City on Wednesday, with Secretary General António Guterres calling out governments and business for “foot dragging, arm twisting and the naked greed of entrenched interests” that have slowed efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

“Humanity has opened the gates of hell,” Guterres said, reeling off a growing list of climate disasters: floods, wildfires and extreme heat. “Climate action is dwarfed by the scale of the challenge. If nothing changes, we are heading towards a 2.8-degree temperature rise, towards a dangerous and unstable world.”

Setting the stage for the UN Climate Conference (COP 28) in the United Arab Emirates in December, Guterres also called for an end to subsidies for fossil fuels worldwide, which the International Monetary Fund (IMF) pegged at $7 trillion in 2022.

Instead, the accelerated agenda shifts fossil fuel subsidies to renewable energy and ends all licensing and public and private funding for new oil, coal and gas. Targets for developing nations are 2040 for coal phaseout and 2050 for economywide net zero.

“Governments must push the global financial system towards supporting climate action, and that means putting a price on carbon and overhauling the business models of multilateral development banks so that they leverage far more private finance at a reasonable cost to developing countries,” Guterres said.

Businesses and financial institutions also must embark on true net-zero pathways, he said. “Shady pledges have betrayed the public trust … using wealth and influence to delay, distract and deceive, and this is shameful.”

Part of the UN General Assembly, the Climate Ambition Summit plenary laid out the issues and potential flashpoints that will resurface at COP 28 as the nations that signed the Paris climate accords in 2015 face the first official global stocktaking of the world’s progress on climate, required by the agreement.

The UN’s initial global stocktaking report, released Sept. 8, said global action on cutting GHG emissions is lagging, and limiting climate change to 1.5 degrees would mean a 43% drop in emissions by 2030 and a 60% drop by 2035. (See UN Report Calls for Quicker Global Emissions Reductions.)

But concerns about progress at COP 28 already are high in some quarters as the U.A.E. has named Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Co., as the conference president. Speaking at a climate conference in Brussels in July, Al Jaber called for an accelerated “phasedown” of fossil fuels, as opposed to a phaseout, supported by a tripling in the deployment of renewables and a doubling of energy efficiency.

“Phasedown” also was the language used by G20 energy transition ministers in the final document coming out of their meeting in India in July, in which disagreements were noted about the extent and nature of any future phasedown.

Pairing emission cuts with increased renewables and energy efficiency is gaining support. Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, said the European Union is working with Al Jaber, Kenya, Barbados and other countries to build a global consensus on the renewable energy and energy efficiency targets ahead of COP 28.

Fossil Fuel Nonproliferation

Guterres billed the summit as an event to recognize the efforts of the nations and organizations moving ahead on ambitious climate action, while also signaling frustration with major polluters, including the United States and China, which were not invited to speak.

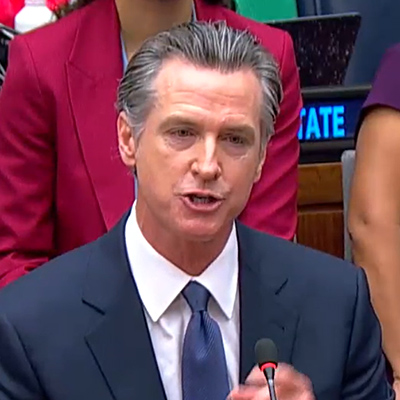

However, California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) earned strong applause for his indictment of major oil companies, following the state’s suit filed Friday against Exxon, Shell, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, BP and the American Petroleum Institute, an industry trade group. (See Calif. Sues Oil Majors over Climate Impacts.)

“It’s time for us to be a lot more clear this climate crisis is a fossil fuel crisis,” Newsom said. “It’s not complicated. It’s the burning of oil; it’s the burning of gas; it’s the burning of coal, and we need to call that out. For decades and decades, the oil industry has been playing each and every one of us in this room for fools. They’ve been buying off politicians. They’ve been denying and delaying science and fundamental information that they were privy to that they did not share.”

Echoing Newsom, Chilean President Gabriel Boric said, “We have to leave fossil fuel behind, and that, in very specific terms, means that we also have to react to the greenwashing that major businesses are undertaking. They continue with that greenwashing, and they’re stepping it up. In some cases, their greenwashing efforts are supported by countries.

“If we’re not able to make these groups yield to our will and to make them yield to the will of the international community as expressed by the leaders here present and by the activists here … the truth is that we won’t hit our targets.”

Prime Minister Kausea Natano of the Pacific island nation of Tuvalu, believes the way forward must include “a comprehensive, multilateral framework that addresses the climate crisis at each root cause. A negotiated fossil fuel nonproliferation treaty would complement the Paris agreement and ensure a global [energy] transition.”

Von der Leyen also promoted wider adoption of carbon pricing as a way to raise money to support clean energy transitions in developing nations. In addition to cutting emissions 55% by 2030, the EU also will work with the UN “to have at least 60% of global emissions covered by carbon pricing by 2030,” she said.

“Today, it’s only 23% [of emissions] that are covered, and this brings in revenue already of $95 billion. Just imagine [if] we could cover 60% of global greenhouse gas emissions, the amount of revenues that we would get to invest in low- and middle-income countries.”

Restructuring Global Finance

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau credited his country’s carbon pricing with GHG emissions that have been trending down since 2019, even as Canada continues to be a major fossil fuel exporter.

The country has a plan for cutting emissions 40% by 2030, that “goes sector by sector, laying out exactly how we will cut our emissions,” he said. “By the end of the year, we will be announcing our framework to cap emissions from the oil and gas sector.”

Regulations on cutting methane emissions from the oil and gas sector 75% below 2012 levels also are being prepared and “will be designed to help us exceed this already ambitious target,” he said.

Gustavo Petro, president of Colombia, another major fossil fuel exporter, argued for a more radical approach to the phaseout of oil and gas, recognizing first the enormous economic and political power of the industry.

Even the goal of net zero is not viable, Petro said, because “the natural absorption capacity of the planet and the oceans, the forests, the jungles is decreasing, so net zero doesn’t really exist.”

Phasing out fossil fuels will require changing the economic structures of countries, like Colombia, that are dependent on the industry, Petro said. “Capital needs to be essentially separated from economic interests where fossil fuels are concerned.

“You need to compensate oil- and gas-producing countries for plugging their deposits, [for] no longer plundering them,” he said. “Rather you need to give them money for mitigation and adaptation. That finance won’t come from a private capital market. These major financial resources can only be produced if we restructure the global financial system.”

A strong advocate for the restructuring of global finance, Mia Mottley, prime minister of Barbados, said, “The reality is that developed countries are going to have to find new mechanisms and new forms of carbon taxes while looking [to] ensure that there is not consequential impact that is incapable of being borne on cost of living. …

“Equally, developing countries will need a new mechanism to reduce the costs of hedging the billions of inward investment required,” she said. “We believe that the [tripling] of the multilateral development bank lending is critical.”

Mottley also hammered on the importance of a well-capitalized loss and damage fund, to compensate developing countries with low GHG emissions for the damage they’ve sustained from climate change. The establishment of a loss and damage fund was a major outcome of COP 27 in Egypt last year, but getting countries or companies to contribute to the fund will be one of the key challenges at COP 28.

“It is painful to continue to see that you are asking us to increase borrowing to build resilient infrastructure for something that we did not do,” Mottley said. “And then at the same time, you want to ensure that you have a loss and damage fund that does not have the adequate means for grant funding to be able to help countries to rebuild. It is unconscionable.”