Hardly a week passes without some organization releasing a study touting the benefits of a huge and rapid expansion of the transmission grid.

Indeed, the idea that the grid needs a rapid expansion to tap renewable resources and decarbonize is an article of faith in the power industry. But opposition to it is not limited to climate-science doubters and fossil fuel interests. (See Counterflow: Big Transmission — Still Not the Right Stuff.)

Both PJM Independent Market Monitor Joe Bowring and Potomac Economics President David Patton, whose firm provides market monitoring for four ISOs and RTOs, have pushed back on the need to rapidly expand the grid.

“Obviously, I’m an economist, and I believe in energy markets,” Patton said. “And the thing about transmission when you’re planning, and then building transmission and guaranteeing cost recovery, is, it’s all happening outside the market.”

While both energy economists agreed that the transmission and distribution systems require central planning, they said it is far from a perfect process and can interfere with cheaper solutions produced by the markets.

“One of the tensions that’s always existed in the PJM market from the very beginning is the tension between competitive generation and non-competitive transmission,” Bowring said. “Generation and transmission do compete at the margin. Transmission can replace generation and vice versa.”

The market monitors are not alone in this position. Vistra Energy, which owns 37,000 MW of generation and serves millions of customers over other firms’ wires, has said the same thing. Vistra told FERC in comments on its still-pending regional planning Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (RM21-17) that the idea that all renewables should be located in resource-rich areas is “too simplistic.”

“It may be more efficient to locate a new resource in a less resource-rich area where interconnection costs are lower,” Vistra said. “The net levelized margin of the resource — including environmental attribute revenues, wholesale market revenue, land cost and net network upgrade costs — will drive efficient development. Ignoring the network upgrade costs ignores a potentially important part of the project economics picture and thus risks increasing overall costs to ratepayers.”

While Vistra has an interest in protecting its fossil fuel generation’s market share, it is not averse to the clean transition. This year, it purchased Energy Harbor’s three nuclear plants, giving it 3,400 MW of carbon-free generation. (See Vistra Pays More than $3 Billion for Energy Harbor.)

FERC Transmission Planning NOPR

FERC’s planning NOPR does not direct the agency to build out all the transmission possible, said Grid Strategies President Rob Gramlich, who has long advocated for grid expansion to address climate change.

“It says: Do an analysis that evaluates the trade-off between one approach that has a lot of remote cheap generation with transmission lines, and another option, that’s more local generation with less spending on transmission — and find the sweet spot between those,” Gramlich said.

Bowring does not sound so different when it comes to planning, saying it needs to be done centrally and rationally, accounting for the locations of load growth and the locations of generation. Where he splits with Gramlich is on how much the cost of interconnecting new resources should be socialized. Bowring says making developers pay for their interconnection gives them the incentive to locate in the right place, rather than requiring customers to subsidize their choice of location.

Burying our heads in the sand about the realities of the future resource mix and adding transmission in small increments will only increase the costs of the networked grid needed to ensure a technologically and regionally diverse portfolio that ensures reliable service 8,760 hours a year, Gramlich said.

“We just have to get away from this system of planning and network through the interconnection process. That doesn’t work in any network in any part of our economy,” he said.

CAISO’s proposal to plan around zones with available transmission capacity now, or under construction — where some areas will be cheaper for interconnection customers than others — is a good example of how things should work, Gramlich said. (See CAISO Proposal Seeks to Address Interconnection Backlog.)

As a supporter of markets, Bowring has doubts about central planning generally, noting that PJM’s regional process has gotten it wrong in the past. He cites the example of the Potomac Appalachian Transmission Highline (PATH).

The $2.1 billion, 765-kV “coal by wire” PATH project was approved by PJM in 2007 to run from a coal generator in St. Albans, W.Va., to New Market in Frederick County, Md. By 2011, however, PJM said the need for the line had moved several years beyond 2015 because of reduced load growth following the Great Recession. After ordering transmission owners to suspend work on the line pending a more complete analysis of all upgrades in its regional transmission plan, the PJM Board of Managers terminated it in 2012.

“Reality keeps changing. We don’t know what the technology is going to look like 20 years from now,” Bowring said. “Do we really want to spend billions of dollars right now on transmission lines based on assumptions about what the technology is going to look like and the level and location of loads?”

Gramlich rejects the notion that the grid would be overbuilt by utilities zealously seeking to expand their rate bases. He said utilities lack the incentives to construct the kind of large regional and interregional lines that may be subject to competition, instead favoring local facilities they can build with little oversight.

In many cases, utilities will look at major transmission as bringing in low-cost, cheaper generation that is going to compete with their own and they will try to actively block its development, he added.

PJM has seen a lot of spending on local transmission projects in recent years, a fact that has come up repeatedly in the debate around FERC’s proposed reforms to planning and cost allocation. In September, the Ohio Consumers’ Counsel filed a complaint with FERC that said utilities in that state alone have planned for $6 billion in local projects since 2017.

No Regrets?

One idea the two market monitors pushed back against was that rarely is a transmission line built that winds up being regretted. While any transmission will be used when it is built and lead to lower congestion on the system, sometimes it is not the best choice.

“The goal is not just to eliminate congestion, it’s to eliminate congestion that has costs higher than the cost of building transmission to eliminate it,” Patton said. “And in some cases, there are other solutions that are much cheaper than transmission that the markets will facilitate.”

Storage, for instance, can deal with congestion either by co-locating with renewable energy or by being built by itself elsewhere on the grid. And while storage might be the best option, overzealous transmission construction outside the market could cause battery developers to abandon such projects, Patton said.

Bowring does not think congestion is a useful metric to justify building transmission, a point his firm, Monitoring Analytics, has made in its state of the market reports. Congestion is ephemeral and locational, and it changes all the time, Bowring said.

“Congestion is not a reason to build transmission,” Bowring added. “Congestion is just the difference between what load pays and generation receives. … So, congestion is zero sum already; it’s not really a metric for anything. If the [financial transmission rights] market worked as intended, load would be repaid 100% of congestion.”

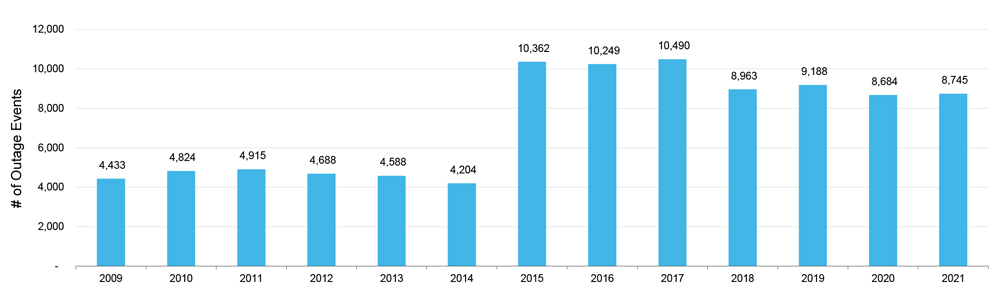

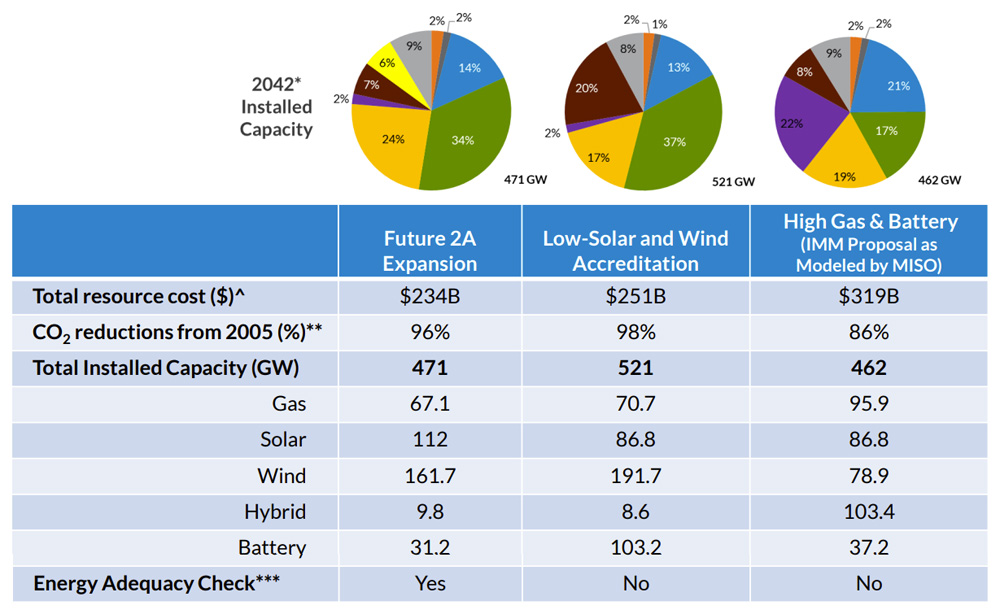

Former FERC Chair Richard Glick said some of the leadership at ISO/RTOs is on board with expanding the grid, noting that MISO CEO John Bear has been advocating for years for transmission expansion to connect renewables. The queues are dominated by renewable energy projects, or hybrid projects where renewables are paired with storage. (See LBNL: Interconnection Queues Grew 40% in 2022.)

“When someone like John Bear from MISO says we desperately need this transmission buildout to keep the lights on, I believe him,” Glick said. “You don’t want to overbuild. But I would say that the consequences of underbuilding are a lot worse than the consequences of overbuilding.”

MISO is home to some of the best wind in the country, but those resources are far from major cities. In contrast, the renewables in PJM tend to be closer to load and therefore require less incremental transmission than in other regions of the country, Bowring said. The one exception to that in PJM is offshore wind.

“I don’t understand why anyone believes that copper plating PJM, or any area, is the solution to adding renewables,” Bowring said.

California used to think it could rely largely on in-state renewable energy to meet its policy goals. But while there are plenty of resources that will continue to be connected locally, policymakers have moved on from that narrow view as the share of renewables has grown, Gramlich said.

“If you do the math, it turns out that Idaho wind and Wyoming wind, and Salton Sea geothermal, New Mexico solar and wind — those complement the resources we have in state. And if you take into account the value of those, and the cost of transmission, it turns out, those are beneficial for California consumers,” Gramlich said. “So, then CPUC has directed utilities to buy power from those areas and the California ISO is tasked with figuring out the transmission to those areas. That’s the way to do it. In MISO, it’s a similar analytical exercise.”

That way of thinking is not isolated to California. Vermont PUC Commissioner Riley Allen, who sits on the FERC-State Task Force on transmission, said in an interview that while local issues like job creation are important, getting the best, most efficient mix of resources should guide transmission planning.

“The economics favor locating capacity and resources where it is inexpensive, and exploiting those opportunities sensibly, while recognizing that these resources are also going to be weather dependent and … using the grid as a mechanism that helps to ensure that no one location is dependent on resources from just one area, it adds an element of diversity that is hard to achieve otherwise,” he said.

While adding renewables to the grid will require some transmission, Patton argued that economics should guide its development more than a centralized plan.

“If we get more and more renewables, and they cause more and more congestion, we should continue to evaluate transmission the same way, which is, you know, is it cost effective to build transmission?” Patton said. “And when the answer is yes, we should build it and then the answer is no, or there’s some lower cost solution, we should not build it.”