With the Port of Philadelphia as a backdrop, President Joe Biden on Friday touted the $7 billion in federal funds going to seven regional hydrogen hubs spread across 16 states as “one of the largest advanced manufacturing investments in the history of this nation.”

The White House and the Department of Energy announced the hubs Friday morning, with the Philadelphia speech following in the afternoon. (See DOE Designates Seven Regional Hydrogen Hubs).

One of the clean energy initiatives created by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), the hubs are demonstration projects aimed at building out commercial-scale clean hydrogen facilities that combine production, storage and end-use applications, while cutting greenhouse gas emissions in hard-to-abate industrial and transportation sectors.

The chosen projects still have to negotiate their awards with DOE. In most cases, the hubs involve a team of public and private stakeholders, such as large corporations, state and city governments, nonprofits and academic institutions.

“These hubs are about people coming together, across state lines, across industries, across political parties to build a stronger, more sustainable economy and rebuild our communities,” Biden said.

As part of his typical stump speech equating climate change with jobs, the president shared details on the Mid-Atlantic Clean Hydrogen Hub, which will include 17 sites in southeastern Pennsylvania, Delaware and New Jersey.

“The Delaware City Refinery in my state, vacant, … and a former jet fuel terminal in New Jersey will use renewable energy like solar power to produce clean hydrogen,” Biden said. “Plumbers, pipe fitters are going to replace and retrofit oil pipelines to transport the hydrogen here, where fueling stations in the Port of Philadelphia in partnership with Philadelphia Gas Works will provide clean hydrogen to people to power trucks [and] heavy-duty equipment.”

Philadelphia and the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority will run their heavy-duty vehicle fleets on clean hydrogen, and Dupont is going to use clean hydrogen to power a large research and development facility in Wilmington, Del., he said.

All told, the hub could produce up to 100,000 tons of clean hydrogen per year and create an estimated 20,800 jobs, Biden said.

The project has been designated to receive $750 million in IIJA funds, supplemented with $2.25 billion in private investment.

Overseen by DOE’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED), the competition for the hub awards was intense. An estimated 79 projects submitted initial applications for the funding, and at least 22 were encouraged to submit full applications, according to an analysis from Resources for the Future.

OCED said the criteria for choosing the final seven included technical merit and impact, financial and market viability, how quickly the project could begin operation and the creation of community engagement and benefit plans covering workforce development, job creation and diversity and equity initiatives.

All prospective hubs also had to show they would be able to produce 50 to 100 metric tons of clean hydrogen per day and cut greenhouse gas emissions.

In addition to the Mid-Atlantic hub, the other winners are the Appalachian (Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio), Midwest (Michigan, Indiana and Illinois), Heartland (Minnesota, North and South Dakota), Gulf Coast (Texas), Pacific Northwest (Montana, Washington and Oregon) and California hubs.

All Things to All Stakeholders

From their inception, the regional hydrogen hubs reflected an attempt to balance the conflicting political and energy industry interests that went into the writing and passage of the infrastructure bill.

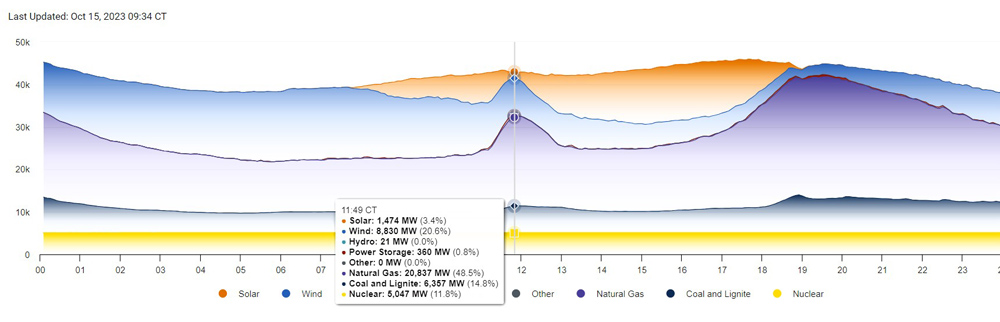

For the fossil fuel industry, the hubs validate its promotion of hydrogen as a complementary fuel that can be mixed with natural gas and transported through existing natural gas pipelines. For clean energy advocates, government support for hydrogen provides another driver for increased deployment of solar and wind, while the nuclear industry gets assurance of ongoing demand for existing and new reactors.

To be all things to all stakeholders, the IIJA spelled out very specific requirements for the hubs.

“Feedstock diversity” was a top priority, requiring that at least one hub produce hydrogen from fossil fuels, one from nuclear energy and one from renewables.

Geographic diversity also was mandated, with each hub to be located in a different region of the United States, using energy resources that are most abundant in that area. At least two of the hubs had to be located in regions with large natural gas resources.

Finally, the IIJA requires end-use diversity, with at least one hub producing hydrogen for electric power generation, one for the industrial sector, one for residential and commercial heating and one for transportation.

Those requirements are well-represented in the final seven projects, and the mixed reception they have received. (See Hydrogen Hub Announcement Draws Praise and Scorn.)

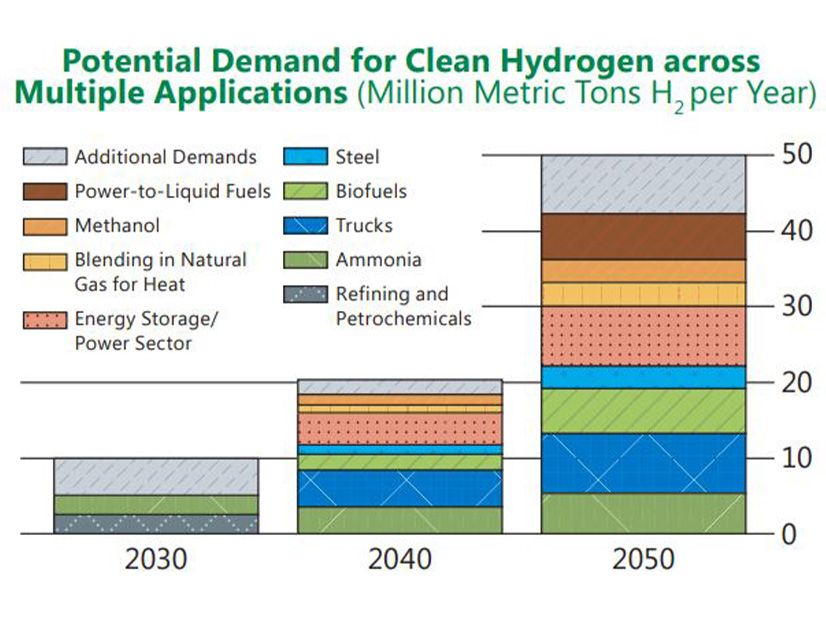

The DOE’s Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Clean Hydrogen report, released in March, frames clean hydrogen as essential for cutting U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in industrial and transportation sectors where electrification may not be a feasible option, such as chemical production or aviation. A rapid scale-up could allow the U.S. to produce up to 10 million metric tons (MMT) of clean hydrogen per year by 2030 and 50 MMT per year by 2050, cutting the country’s GHG emissions 10% below 2005 levels, the report says.

With their combination of production, storage and end-use applications, the hubs are aimed at jump-starting expansion of clean hydrogen demand and infrastructure over the next three years.

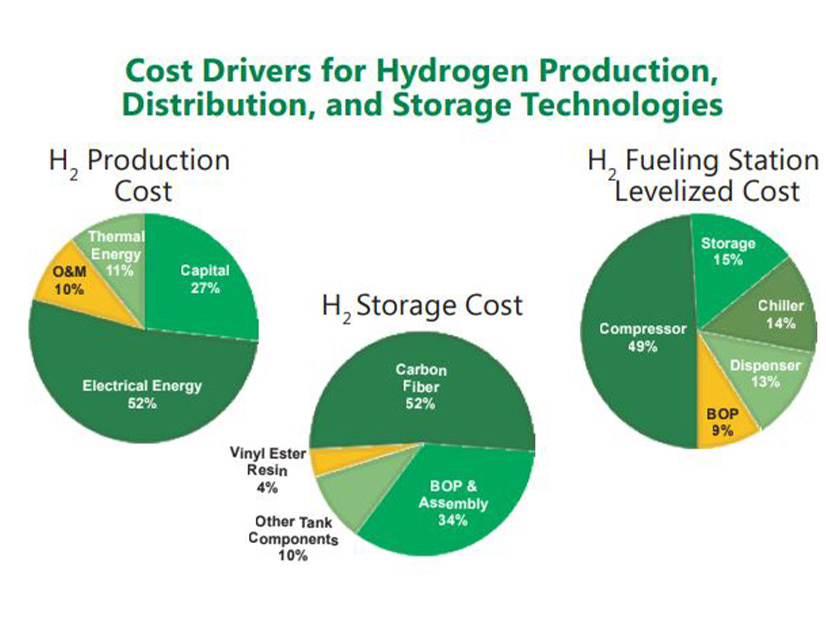

They also will benefit from clean hydrogen incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), including either a 30% investment tax credit or a production tax credit of up to $3 per kilogram.

With the IRA incentives set to last 10 years, private investment then could become a core driver of growth as the industry scales and prices fall, the report says. “These investments, including the build-out of midstream distribution and storage networks, will connect a greater number of producers and offtakers, reducing delivered cost and driving clean hydrogen adoption in new sectors.”

But the report also sees significant headwinds to commercialization of clean hydrogen, noting that even with the regional hubs and tax incentives, demand may lag production. In July, DOE announced it would use another $1 billion from the IIJA to develop a “demand-side support mechanism” for clean hydrogen. For example, the agency might act as a “market maker,” buying clean hydrogen from the hubs and then selling it to offtakers. (See DOE to Invest $1 Billion to Build Demand for Clean Hydrogen.)

Deployment of sufficient solar and wind to produce “green” hydrogen also could affect market growth, the report says. Without enough solar and wind, by 2050 the U.S. could see 80% of its clean hydrogen produced from natural gas with carbon capture.