FERC issued a long-awaited order Dec. 18 on co-location of load and generation in PJM, which is meant to facilitate service for data centers while preserving grid reliability for consumers (EL25-49).

“Today’s order is a monumental step toward fortifying America’s national and economic security in the AI revolution, while ensuring we preserve just and reasonable rates for all Americans,” FERC Chair Laura Swett said in a statement. “I look forward to tackling more of these critical national issues with my colleagues in the new year.”

The case dates to 2024 when Talen Energy and Amazon Web Services tried to expand an existing data center plugged into the IPP’s Susquehanna nuclear plant and FERC rejected that request. (See FERC Rejects Expansion of Co-located Data Center at Susquehanna Nuclear Plant.)

Then, in February 2025, FERC launched a show-cause proceeding looking into the issues around co-location in PJM that led to the order issuing new rules. (See FERC Launches Rulemaking on Thorny Issues Involving Data Center Co-location.)

The rules require that any existing plant used to serve co-located load can start such a contract only after completion of any needed transmission upgrades to ensure reliability after the capacity is withdrawn from the grid, which Swett told reporters would ensure reliability.

FERC asked PJM for a report within 30 days on the ways it is considering maintaining resource adequacy in its Critical Issue Fast Path stakeholder process. FERC met just a day after PJM’s capacity market cleared short of its reserve margin target, so each of the commissioners mentioned resource adequacy concerns in their comments. (See PJM Capacity Auction Clears at Max Price, Falls Short of Reliability Requirement.)

“PJM has great momentum in addressing, currently, in their stakeholder process, various approaches to getting shovel-ready generation to the front of their process,” Swett said. “And we didn’t want that momentum to stop, which is why we are requiring this informational filing within 30 days, and that will include detailed scheduling proposals, and we’re going to keep a close eye on that to ensure that we have enough reliability.”

The order found PJM’s tariff unjust and unreasonable because it was unclear on the rates, terms and conditions that applied to customers seeking co-located service.

To submit a commentary on this topic, email forum@rtoinsider.com.

FERC directed changes to the interconnection rules, requiring any interconnecting generators that plan to be paired with a co-located load specify the customer being served. Generators with co-located loads can ask for interconnection service below maximum facility output and can use existing procedures to speed up the interconnection process if it requires no network upgrades or further studies.

The changes allow interconnecting generators to request provisional interconnection service and surplus interconnection service.

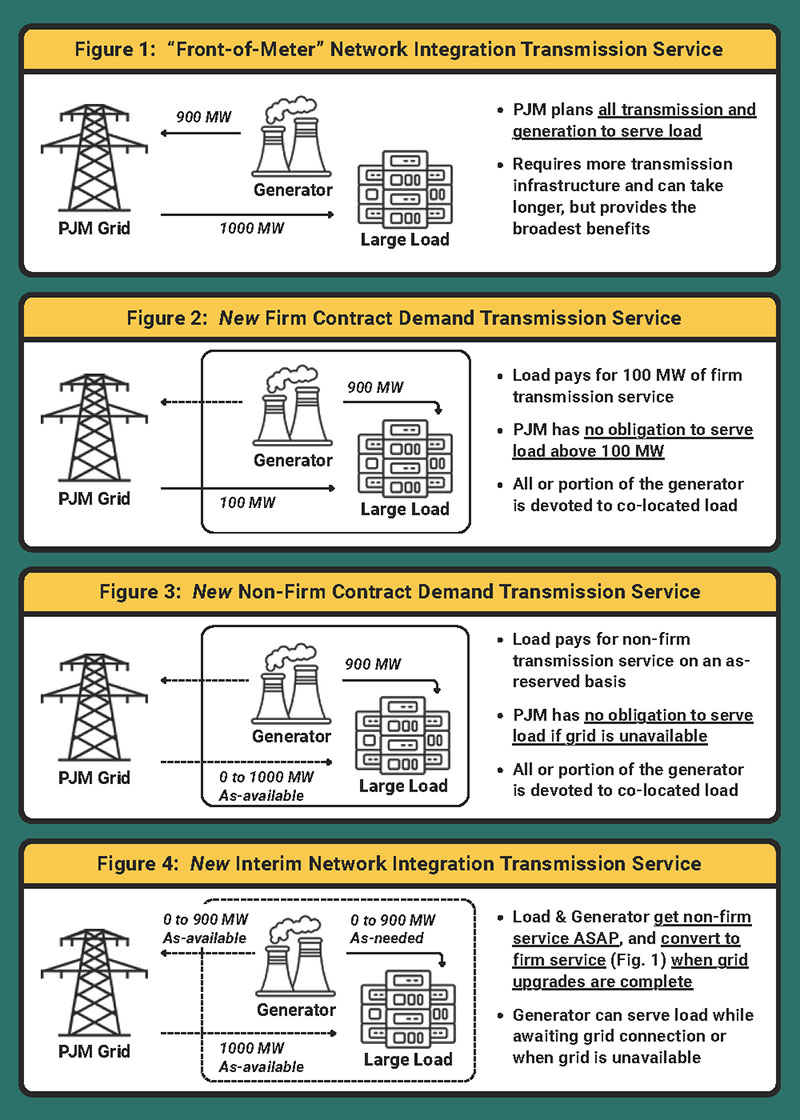

PJM now must revise its tariff to require eligible transmission customers serving co-located load to choose from several transmission service options.

Eligible customers can pick from four options — network integration transmission service (NITS), a new and interim non-firm service customers use while waiting for NITS, a new firm contract demand transmission service, and a new non-firm contract demand service.

Under the new firm contract demand service, PJM is responsible for serving some load from a co-located load customer, but nothing above that specific megawatt level. The non-firm contract demand transmission service could have the co-located customer served entirely by the grid if the capacity is available, but if it is not then PJM has no obligation to serve the customer.

The firm contract demand transmission service and non-firm contract demand transmission service are the subject of a paper hearing that FERC will use to determine their just and reasonable rates, terms and conditions. PJM’s initial briefs for that hearing are due Feb. 16, 2026.

“The replacement rate will ensure that eligible customers on behalf of co-located load take transmission service and incur transmission costs in a way that is at least roughly commensurate with their derived benefits,” FERC said. “The replacement rate will also ensure that eligible customers on behalf of co-located load are able to take transmission services that reflect their actual impact on the transmission system, which in many cases may be more limited relative to conventional front-of-meter load and generation.”

Regardless of which option customers pick, they will have to pay for regulation and black start service on a gross demand basis. FERC is specifically taking comments on whether customers on non-firm contract demand service should face other fees given that regulation and black start rely on the transmission system.

The order also found the RTO’s rules on behind-the-meter generation (BTMG) no longer are just and reasonable because the resources are not fully accounted for in resource adequacy planning and shift costs onto other customers. The BTMG rules will have to be updated, with a transition period and grandfathering for existing contracts.

The order declines to address jurisdictional matters on the interconnection of retail loads served by a co-location agreement. That issue is in front of FERC in Energy Secretary Chris Wright’s ANOPR on the interconnection of large loads.

Rosner and Chang Weigh in with Concurrences

The order drew a pair of concurrences from Commissioners David Rosner and Judy Chang, with Rosner explaining how FERC is trying to reconcile two fundamentals of utility regulation.

“We are trying to meet surging demand while upholding two fundamental values that underpin the electric industry in our country: first, that all customers have a right to receive electric service on a timely basis; and second, that electric service should be reliable and affordable for all customers,” Rosner said. “Given the scale of new large loads putting demand on our grid today, it is clear that fostering both of these values requires intervention.”

The order seeks to break the logjam by requiring PJM rules to allow for the co-location of load at generators and load flexibility, which cuts large loads’ reliance on the grid while ensuring they pay their fair share, Rosner said.

Chang’s concurrence brings up whether the new transmission service options for large loads should come with a minimum charge to avoid cost shifts to other customers.

“All generators, and as relevant here, all generators that are part of co-located arrangements, rely on the PJM transmission system to operate,” Chang said. “Without the PJM grid, co-located loads and their associated generators would be islanded.”

The costs for black start and regulation are nearly inconsequential so just paying for those two ancillary services does not mean co-located loads are paying their fair share, she added. If co-located loads do not pay for anything else, they will not contribute to PJM’s administrative costs that are recovered via transmission charges.

For the paper hearing, the order asks about developing transmission charges to ensure co-located loads pay their fair share. Chang argued that could be accomplished with a minimum charge and sought comments on the concept.

“This minimum charge would provide a floor to the co-located load’s cost responsibilities to pay for a portion of system costs, commensurate with the benefits that the co-located load receives from the system, even where it plans to draw little or no energy from that system,” Chang said.

Early Reactions from the Industry

The Electric Power Supply Association (EPSA) includes members that have considered co-location deals, and its CEO Todd Snitchler called FERC’s order a welcome move.

“The optionality that the commission laid out at the open meeting is helpful in recognizing the variety of co-location approaches that may be utilized to meet the moment,” Snitchler said. “Clearly, this is the first step in a process that will require quick action and durable consensus from many stakeholders and highlights the urgency in getting solutions onto the system, and for that we applaud FERC’s approach. We look forward to working with FERC and other stakeholders to deliver solutions that enable new technologies, encourage the addition of new generation and ensure the continued provision of reliable, cost-effective wholesale power for all customers.”

Advanced Energy United called the order promising, but like the commissioners themselves said at the open meeting, it was only part of the answers needed around resource adequacy.

“The capacity auction shortfall, along with this new FERC order, should be seen as a warning to PJM that more system-wide issues still need attention, including transmission build-out, generator interconnection, capacity reforms, and better integration of demand and distributed energy resources,” AEU Director Jon Gordon said in a statement. “PJM needs to heed FERC’s message that grid flexibility enables speed, affordability and reliability. As PJM proposes new rules to enable fast-tracking large load interconnections, it should prioritize the advanced energy technologies that are quickest to build and enable flexibility.”

PJM Delays Decision on CIFP

FERC’s order recognizes that regardless of the rules around co-location, PJM needs more resources. So it asked the RTO to file a report within 30 days on the options it has examined there.

During the Dec. 17 Members Committee meeting, PJM Board of Managers Chair David Mills revised the target for selecting and submitting a proposal to FERC from December to January. With a dozen proposals submitted, more time is needed for the board to grapple with all the issues raised by the CIFP process and the proposed solutions. (See PJM Stakeholders Reject All CIFP Proposals on Large Loads and PJM Stakeholders to Vote on Large Load CIFP Proposals)

“I had not expected a dozen proposals, and obviously the proposals contain many important elements for the board to consider,” Mills said.

The board also has two members who joined partway through the CIFP after Robert Ethier, a former ISO-NE executive, and Le Xie, faculty co-director of the Power and AI Initiative at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, were appointed to the board in September. (See PJM Members Confirm 2 Board Nominees; States Call for Governance Overhaul.)

The PJM-sponsored proposal would create a 10-month Expedited Interconnection Track for state-sponsored resources, particularly those paired with large loads. Utilities submitting large load adjustments would be required to ask customers whether their projects are duplicative, to identify instances where developers may be considering multiple sites.

The RTO’s price responsive demand (PRD) resource class would be reworked to replace the dynamic retail rate with an energy market bid price and align the resource class with DR by requiring it to respond to dispatch regardless of bid price, subject it to performance assessment interval penalties and mirror their 30-minute energy bid price caps.

The highest vote-getter was a Southern Maryland Electric Cooperative proposal built off PJM’s package, but with a lower energy market strike price for PRD.

A joint package from Amazon, Calpine, Constellation Energy, Google, Microsoft and Talen Energy would establish an alternative reliability backstop triggered if a Base Residual Auction (BRA) clears below 98% of the reliability requirement, allowing eligible resources to submit capacity offers for up to seven-year terms. That would include new or reactivated resources; existing resources with offers higher than the maximum price for the BRA that cleared short; and traditional DR.