ROSSLYN, Va. ― Getting transmission built in the U.S. today takes intensive community, workforce and supply chain engagement, while ensuring communication on all those fronts starts early and often, according to a panel of transmission developers at the American Council on Renewable Energy’s recent Grid Forum.

It doesn’t work to take on any one part of a project — such as supply chain — in a vacuum, said Steve Caminati, vice president for government and regulatory affairs at Pattern Energy, which recently started construction on the 550-mile SunZia transmission line.

“You’re trying to do that as you’re trying to line up permitting, as you’re trying to line up financing, as you’re trying to figure out the tolling arrangements through the line, [and] the projects that are going to utilize the line. You’re trying to land all these planes simultaneously,” Caminati said.

“It’s like playing a three-person game of chess or something where you’re trying to get all the pieces together,” agreed Stuart Nachmias, CEO of Con Edison Transmission. “Strategic partnerships and relationships are certainly one piece of it. So, we really need to think, how is this going to unfold, because the need is tremendous.”

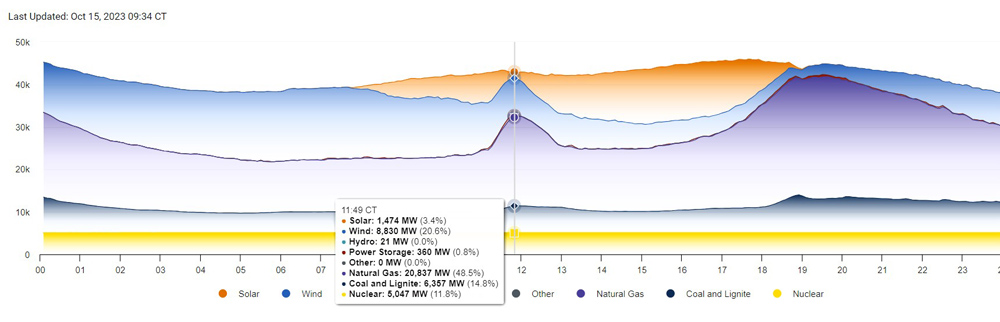

With an estimated 2,000 GW of renewables and storage sitting in RTO/ISO interconnection queues across the country, the need for rapid expansion of the country’s transmission system, and in particular, interregional high-voltage, direct current (HVDC) lines, has become an electric power industry imperative. The Department of Energy’s draft Transmission Needs Study, released in March, called for a 57% expansion of the existing grid by 2035.

But the obstacles to permitting and building such projects have become almost legendary. SunZia’s 525-kV line, which will bring wind energy from New Mexico to Arizona, took 16 years to permit. Pattern got the final go-ahead from the Bureau of Land Management in May. (See SunZia Project Wins Final Approval, Signs Offtakers.)

But while discussing the difficulties involved in such projects, the panel also focused on successes and lessons learned, with a strong focus on community and stakeholder engagement.

Nachmias said getting to know upstate communities was critical to the success of the recently completed New York Energy Solution project, a 67-mile, 345-kV line installed in an existing right-of-way.

“I would often meet with the team, and they would tell me … about the beekeeper, about the llama lady, about all the people on the right-of-way,” Nachmias said. “We had people who live there and who brought cookies to our field crews, and the reason they did that is we engaged with them.”

A major selling point for the project was that it was going to remove about 600 old lattice transmission towers and replace them with 400 monopile towers, he said.

“We showed renderings of what the right-of-way would look like; we gave local community centers and libraries [computers] and encouraged people to go in and look at the maps, which indicated exactly where the towers would be,” Nachmias said. “We heard if there were concerns; we didn’t promise we’d be able to move towers, but … if there was a request to move a little bit here or there, we did so.”

Job 1: Name Recognition

Patrick Whitty, senior vice president for public affairs at transmission developer Invenergy, stressed the importance of ensuring that interregional transmission lines deliver benefits — and power — to the states they cross. The company’s Grain Belt Express, a 5-GW, 800-mile line starting in Kansas and running across Missouri and Illinois to Indiana, was originally designed to deliver 500 MW of power to Missouri, Whitty said.

“The desire to see more local delivery and more power delivered locally was a driving factor of [Missouri] stakeholders … and so Invenergy went to work, looking at how that issue and how that stakeholder input could be reflected back into positive changes to the project,” he said.

The Missouri Public Service Commission on Wednesday approved Invenergy’s updated plan for the project, which will now deliver 2,500 MW to the state.

Invenergy also had to do basic public education, Whitty said.

“The name of a company like ours isn’t one that everybody knows how to pronounce when they read it. … So, we have to work from the very first minute to build credibility and to educate about the need and what we’re doing and why we’re there,” he said. “One aspect that’s really important is you’ve got to get a team that is familiar with and drawn from the places you’re working.”

Caminati added that building relationships, even with people or groups opposed to a project, can be important.

“It’s hard to build a $10 billion infrastructure project and not have opposition,” he said. But even opponents of SunZia have conceded that Pattern listened to them and has tried to mitigate some of their concerns, he said.

Communication across a range of stakeholders can be especially critical in heading off misinformation, Nachmias said.

“Don’t underestimate that people make stuff up, and things that are not true [can] get a life of their own,” he said. “If you don’t think about that and get ahead of it, so there’s consistency and accuracy and factual information being shared, that’s when you start to lose control and then you can have more delays.”

Workforce and Supply Chains

Workforce development requires striking a balance between immediate needs for project construction and a longer-term vision for providing local workers opportunities to build careers, the panelists said.

Pattern is looking to align incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act — which are often linked to projects paying prevailing wages and working with registered apprenticeship programs — with its own conversations with local and state workforce development groups, including labor unions, Caminati said.

Construction jobs may be temporary, so the company is trying to figure out how its transmission projects can be “about building a more robust permanent industry,” he said.

Yearslong permitting timeframes do allow developers to work with local unions and community colleges to stand up training programs, Nachmias said, but even then, getting the mix right can be tricky. “We need all levels,” he said. “We need people who are going to be in the field. We need electrical engineers … it’s not popular in schools, but we need them.”

Whitty shared an anecdote about a New Mexico project Invenergy has in early development. In a community meeting in Hardin County, one of the local residents repeatedly stressed how sparsely populated the area is. “I ended up looking it up, and it’s the 15th-least-populous county, by people per square mile, in the country, and that includes counties in Alaska,” he said.

The issue was brought back to the construction team, he said, to ensure they could be working on it ahead of time.

Increasingly, community benefits packages, with money for workforce training, are becoming a standard part of Invenergy’s project planning, he said. “We’ve realized that almost every market we’re working in, that’s an essential piece of what the industry looks like.”

Whitty also spoke on supply chain challenges Invenergy is facing, particularly in securing converter stations that are an essential component of HVDC lines, “where the power switches from AC to DC and vice versa.”

The stations are “incredibly complex, incredibly expensive facilities that require years of planning and engineering and manufacturing work,” he said, and in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the global supply chain has been largely bought up by TenneT, the Dutch-German transmission operator.

Developers for U.S. transmission projects typically need two or three converter stations but could find themselves “in the back of the line” behind TenneT, he said. Invenergy is working with Siemens on equipment for the Grain Belt Express and also negotiating for the power lines it will need for several projects at once “to enhance certainty across the whole portfolio,” he said.

‘Do the Cheap Stuff First’

The transmission developers’ panel, which closed out the forum, provided an on-the-ground counterpoint to the keynotes on high-level federal policy that started the conference.

FERC Commissioner Allison Clements framed the U.S. energy transition now underway as a response to the opportunities and challenges of “extreme weather, a rapidly changing resources mix, aging, outdated infrastructure, [and] cyber and physical threats.”

“I am focused on whether our federal regulatory framework is aligned with what’s happening in the world,” Clements said. “Throughout history, there have been lots of moments where regulations lagged behind where the markets want to go. I think this is the ultimate example.”

FERC’s role is to modernize the rules, to facilitate change while ensuring affordability and reliability and without favoring any specific technology, she said. “That’s where the country is moving, so that’s what this commission is going to do.”

The way forward, she said, should be “data-driven, reality-based planning and market reform. Make … the low-cost, easy changes first while taking the time to grind the regulatory machine for deeper reform.”

FERC Order 2023 on interconnection is a first step, though it’s on hold as the commission considers the multiple requests it has received for a rehearing. (See FERC Order 2023 Gets Rehearing Requests from Around the Industry.)

But, Clements said, “If you are thinking about what you can do near term … you have to start with grid-enhancing technology on the grid, period. You cannot stand up and say you represent consumers and their interests if you are not serious about getting grid-enhancing technologies.”

“If we want to create the room for interconnection, if we want to create the opportunity to invest in relatively expensive transmission alongside, we have to do the cheap stuff first,” she said, noting that support for grid-enhancing technologies — such as advanced conductors and dynamic line ratings — is included in Order 2023.

While the bigger issue of market reform is hard if not impossible to simplify, Clements believes the next step is to “get regional transmission system planning done and align our interconnection process with our regional planning process. If we finalize that, we have a chance of moving system planning out from under this ill-suited interconnection process,” she said.

Rep. Scott Peters (D-Calif.) took on the issue of permitting reform in an impassioned keynote address. Instead of combating the climate crisis with the urgency it requires, he said, “we’re debating whether a decade is an appropriate amount of time to construct a single high-voltage transmission line, an offshore wind facility or a geothermal plant.”

With the IRA and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the previous Congress provided the money for a strong response to climate change, he said, but “we will still fail if we don’t act faster.”

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was written and enacted into law when “our environmental imperative was to stop dirty projects,” he said. “It was a law that responded to the challenge of its time, but it didn’t come down from Moses on stone tablets.”

NEPA can and should be updated to meet the need to build new, green infrastructure that can cut emissions, Peters said. “Climate activism is about building stuff, not stopping stuff,” he said.

Peters and Sen. John Hickenlooper (D-Colo.) recently introduced the Building Integrated Grids with Inter-Regional Energy Supply (BIG WIRES) Act, which would require all RTOs and ISOs to be able to transfer at least 30% of their peak load to other regions. With the House of Representatives still without a speaker, Peters said he didn’t know if the bill could pass this session. (See Hickenlooper and Peters Introduce BIG WIRES Act.)

But Peters said he is working with colleagues across the aisle on a permitting reform package that “would improve community input and fix the broken judicial process.”

A main obstacle to permitting reform could be the political process itself, Peters said. “Transmission has become seen as … the way to displace oil and gas. If it’s perceived as that, then we’d have problems. … Transmission is needed for all sorts of projects. It’s a reliability issue; it’s a cost to consumers issue and a competition issue.

“The learning we need to pursue right now is to make sure people understand transmission is bigger than just renewables.”