FERC commissioners and the industry and state witnesses before them at the commission’s annual reliability technical conference Nov. 9 were split on whether EPA’s latest greenhouse gas rule for power plants can be implemented reliably and affordably.

Chair Willie Phillips opened up the afternoon’s panels focused on EPA’s proposal under Clean Air Act Section 111(d) by noting that FERC’s first job is to maintain reliability. (See EPA Power Plant Proposal Gets Mixed Reception in Comments.)

“For half a century, EPA has set and enforced the emission standards that apply to every power plant in the nation,” Phillips said. “We remind ourselves again, at the outset of this conference, that our piece of the electric power puzzle is defined by the Federal Power Act. We do not build, certificate or authorize the construction or retirement of power resources. That responsibility lies with the states. We also do not have the authority to second-guess EPA’s regulatory choices.”

FERC’s task was to better understand how the rule would impact the grid going forward, with the knowledge that predicting future outcomes is a “fraught task,” he added.

Joseph Goffman, principal deputy assistant administrator for EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation, laid out the details of the rule, which he noted was still under development and would likely change before it is finalized.

“The proposed carbon pollution standards are in fact crucial to addressing the urgent need to reduce climate-destabilizing carbon dioxide pollution from the power sector,” Goffman said, “and an important part of the agency’s broader efforts to address the multiple health and environmental impacts of the power sector, while supporting the continued delivery of reliable and affordable electricity.”

The proposal includes varying compliance levels for coal and gas plants that depend on how long they plan to keep running and how often they are actually dispatched by grid operators, Goffman said. The rules will allow the industry to keep building uncontrolled combustion turbines needed to meet peak demand, while the only coal plants facing the strictest requirements are those that keep running past 2040.

The rule will also be implemented by states’ environmental agencies, and they will have some flexibility to make the rules workable. EPA is also proposing a transparent exemption process for units critical to reliability that cannot comply with the rule — as it did for the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS) a decade ago, Goffman said.

“I like to think about us as being maybe in the fifth inning of this process,” Goffman said. “We haven’t even gone to the bullpen yet. So, there’s a lot of work that we still understand that we must do on the path to finalizing these rules. And we are committed to engaging with reliability stakeholders as we develop the final rule.”

The last half of the game will involve EPA iteratively refining its rule and turning to FERC, state regulators, the industry, grid operators and others to get their expert opinions on any changes, he added.

The rule would require the longest-lived and most used fossil power plants starting in the 2030s to use carbon capture and storage (CCS), or clean hydrogen at scales that have yet to be proven for either technology. Their lack of viability has been a common criticism, and Phillips asked Goffman to address it.

EPA has designated those technologies as the “best system of emission reduction,” but states will ultimately get to pick the strategies that work for them. Both CCS and clean hydrogen have significant federal backing under the Inflation Reduction Act as well, Goffman said.

“We’ve had reports from various RTOs, in fact, almost all of them, that they’ve had unexpected retirement rates that they didn’t anticipate,” said Commissioner James Danly. Coupled with the difficulty of fully using all the incentives from the IRA and issues around interconnection, it is likely that law will not fully spur the massive growth in new clean energy some have predicted, he argued. Thus, the process of replacing the emitting plants with new clean capacity will not be as robust as EPA might think.

“You’ve laid out a lot of issues that I think we are going to have to address in terms of how we account for potential retirements,” Goffman replied.

Even without EPA’s rule, those issues are going to be facing FERC as the industry is transitioning away from fossil fuel to renewables and other cleaner resources because of other policies and market forces, said Commissioner Allison Clements.

“We face the need for markets to evolve to send the right signals to provide resources with the revenue certainty and to provide services we need,” Clements said. “That’s within FERC’s jurisdiction and is in need of change before we even get to this policy.”

Finalizing compliance with Order 2023 will help on that front, and FERC could also take up issues around retirement notifications to help remedy that issue, she added.

Less Room for Error

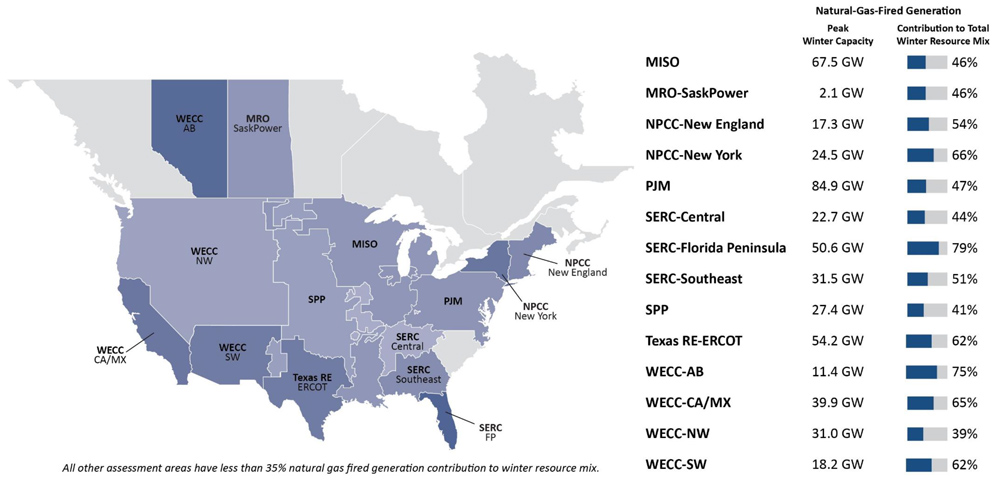

PJM released a paper early this year, before EPA released its proposal, projecting it would see 40,000 MW of retirements by the end of 2030, but it has already seen some announced retirements since then that it was not expecting, so the actual numbers could be bigger, said Mike Bryson, the RTO’s senior vice president of operations.

“We look at certainly the impact of the IRA, which I appreciate has a lot of stimulus in there,” Bryson said. “But we also look at the Ørsted announcement about Ocean Wind 1 and Ocean Wind 2 — 7,500 megawatts, which was supposed to be replacement megawatts.” (See Ørsted Cancels Ocean Wind, Suspends Skipjack.)

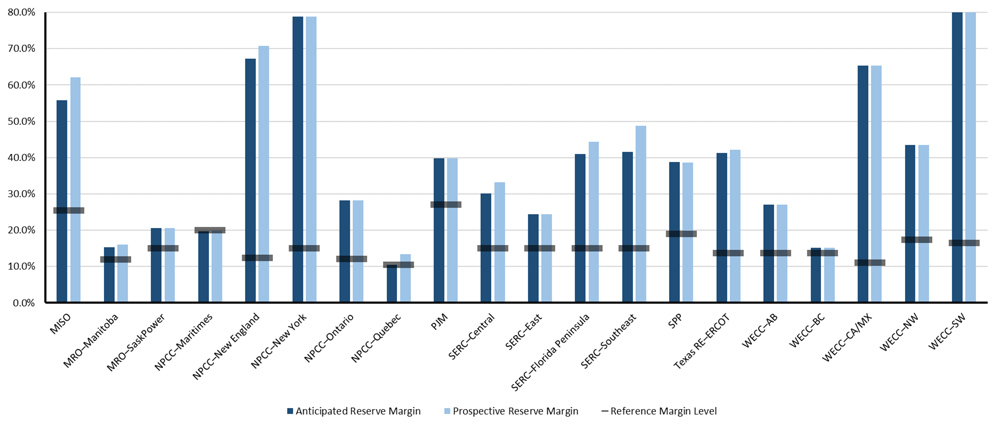

While PJM’s markets worked to help reliably transition its fleet from the MATS rule, which led to significant retirements of coal plants, its markets are different now. The reserve margin is thinner, and there is less room for error this time around, Bryson said.

Other industry speakers were more blunt, with Eastern Kentucky Power Cooperative CEO Tony Campbell, who was testifying for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, calling the rule “unlawful, unworkable, beyond salvage and disastrous for grid reliability.”

“Even if we put aside the enormous cost involved, the proposed rule relies on CCS and clean hydrogen, neither of which are ready at levels and scales for a sound economy that requires certainty, and not in all regions of the country,” Campbell said. “The infrastructure needed for both technologies is not now and will not be in place at the scale to meet EPA deadlines.”

Beyond the costs, both technologies need pipeline infrastructure, which has not been easy to build for natural gas, and that at least has an established regulatory regime, he added.

Campbell was not alone in questioning the rule’s legality, but Edison Electric Institute Vice President General Counsel Emily Sanford Fisher said that issue would ultimately be decided in the coming years in the courts.

EEI’s investor-owned utility members have embraced the clean energy transition, with Fisher noting the industry has met the goals of the Clean Power Plan even though it never it went into effect, and 2022 saw emissions equal to 1984’s.

“Regardless of any final EPA regulations addressing greenhouse gas emissions from … the fossil generating fleet, the clean energy transition is not going to be easy,” Fisher said. “Challenges do not mean, however, that this transition is impossible, or that our larger goals about a resilient equitable, affordable, clean energy future should change.”

Those challenges will require working across myriad stakeholders to address them, and the industry and policymakers should be prepared for some “bumpy” progress occasionally, she added.

EPA is likely paying close attention to the legal issues around its rule, given its experience with the Clean Power Plan being overturned, noted Analysis Group Senior Adviser Susan Tierney, who had released a paper before the technical conference explaining how the industry could meet the proposed rule’s requirements reliably. It echoed arguments she made for other EPA rules issued under the Obama administration.

“In each instance in the past dozen years, the industry and other stakeholders predictively stepped up to ensure that actual reliability was not compromised,” Tierney said.

Some of the particulars this time are different than in the past, but there are also reasons to be assured that a final EPA rule will not jeopardize reliability, she added.

Colorado is well underway to deep decarbonization, pushed by state policy and being one of the few states to benefit from plentiful wind and solar without the need for massive transmission lines, said its Energy Office’s executive director, Will Toor. It expects all coal plants to be retired before EPA’s requirements kick in, while its natural gas fleet will operate at low capacity factors, balancing a growing share of wind and solar.

“We do believe that it will be important as the EPA finalizes the rules to ensure maximum flexibility for states to comply in the most cost-effective manner,” Toor said. “We urge EPA to maximize the ability of states to use trading, massive rate-based averaging and other approaches. This should include an ability for states to recognize the changing use of existing gas plants over time.”

By 2030, only one gas unit in the state is expected to approach a 20% capacity factor, which falls to 11% before the end of that decade, he added.

“I’ve got to believe that before you get investors in, a 20% capacity unit is going to be rate based, and therefore the owners are going to be guaranteed cost recovery,” said FERC Commissioner Mark Christie.

Toor answered yes, and Christie noted that no investors are going to want to build additional natural gas plants that run so rarely. But Toor said his state has found that is the cheapest way to operate the grid going forward, even including the total costs of natural gas plants.