DUBAI — The energy transition will be messy, but mistakes along the way are essential as the world attempts to solve the complex and broken ecosystem that caused climate change, leaders from the industrial and financial sectors said at a McKinsey panel on the net-zero transition.

The panel took place in COP28’s Green Zone, a short walk from the Blue Zone, where governments and NGOs are negotiating commitments and reporting on progress toward the Paris Agreement.

“The idea of orderly transition is a wrongheaded idea,” said Lord John Browne, managing director of climate growth equity fund General Atlantic and co-founder of BeyondNetZero. “It’s testing and trying: no one has the answer.”

This “test and try” approach to solving the energy transition can be seen in everything from incentives to financial structures to supply chains, he said. Governments and industry make mistakes in almost all aspects of the transition, but a poorly designed incentive with unintended consequences is better than no action at all, and those actions help figure out what does work, he added.

Accepting and embracing the three steps forward, one step back nature of the transition is essential, said Tom Linebarger, former CEO and chairman of Cummins, because without it, “it causes people to wait for the perfect solution, for some technologists to deliver something that’s going to be free for everybody and really perfect.”

“We’re going to be disappointed by the side effects of everything from batteries to hydrogen manufacturing. There are going to be things that we didn’t predict, there are going to be things that don’t work the way we want,” Linebarger said. But “if we don’t get started, we don’t solve those problems.

“The question is, how do you move when you know you’re going to make mistakes? How do you get going to take a step forward? That’s really the challenge in front of corporations, investors, people who are trying to advance the cause.”

Too many corporations wait for the risk to be removed, particularly in industries where commodity prices drive decisions, but Linebarger said companies must act in the short run, with the expectation they’ll learn and win over time.

Investing in the energy transition also means accepting that work will need to be redone over time, Browne said. For example, early wind farms are being redone with more powerful turbines, and solar farms built today will be redone when more powerful panels reach the market.

Even with alignment about the problems and commitments being made by governments at COP28 to solve them, there’s a $2 trillion shortfall of the $4 trillion a year needed to reach climate goals, said Anne Finucane, chair of Rubicon Carbon. “You can figure your way to $2 trillion through the market, just based on 20% equity and 80% financing” that’s typical from banks, private equity firms and asset managers. “The question is what to do about the other $2 trillion.”

Carbon taxes are seen as a necessary tool, but there’s no consensus on whether they should be voluntary or required, and whether voluntary carbon taxes are underpricing carbon.

Panelists said private sector funding alone wouldn’t be sufficient to close the investment gap, and that public and private partnerships are essential. “This is a catalytic moment because it will push governments to do the right thing,” Lord Browne said.

Mapping a Path to Net Zero

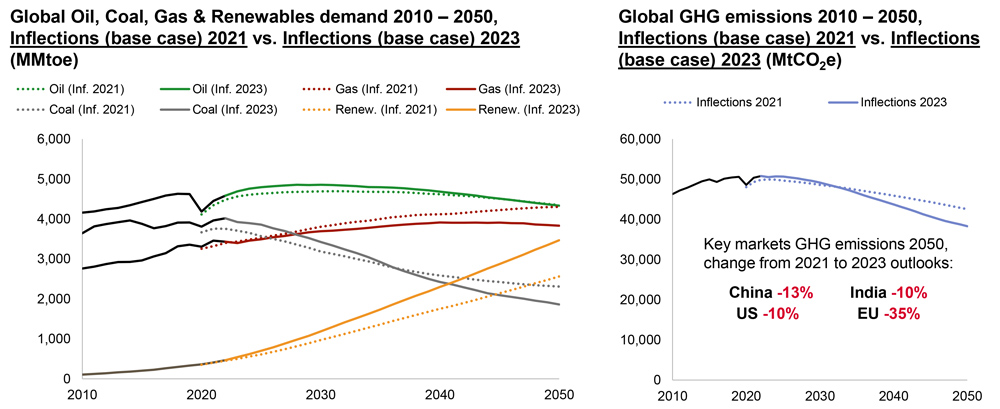

The panel coincided with McKinsey’s release of a new report: “An Affordable, Reliable, Competitive Path to Net Zero,” which argues for “not one objective, but four interdependent ones: emissions reduction, affordability, reliability and industrial competitiveness.”

Designing an achievable path is critical, said Daniel Pacthod, senior partner at McKinsey, because the world is far from achieving the Paris Agreement targets. “We’ve seen this in the global stock takes: we’re not going to be remotely close to where we want to be. We are closer to 2.5 degrees in, more than 1.5.”

The report looked at seven principles for decarbonization and said applying two principles — deploying lower-cost solutions and using R&D and other measures to double the expected rate of cost declines — “could substantially improve the current trajectory of emissions and help limit warming to what the Paris Agreement envisions.”

While the potential of a pathway based on those principles is hopeful, the report also warned that “a poorly executed transition could make energy, materials and other products less affordable, compromising economic empowerment. It could also make the supply of energy and materials less secure and resilient, and it could render some countries and companies less competitive. If that happened, progress toward net zero itself could stall.”