A newly published Berkeley Lab study finds that sale prices temporarily decrease for property located within a mile of newly announced and newly built utility-scale wind projects.

The conclusion runs counter to earlier studies published by the lab, some of which were compiled by some of the same researchers but relied on limited sales data.

During a webinar Dec. 13, one of the authors said vastly more real estate transaction data is available now than a decade ago, many more large-scale wind turbines have been erected, and the methodology for analyzing the information has evolved.

The bottom line: Shortly after a commercial wind turbine site is announced, houses located within a mile begin to sell for less than those three to five miles away from the same site. Over the next nine years, the difference grows to 11% on average, then gradually declines until the disparity is statistically insignificant.

“We see a dipping of values after the announcement of the project that kind of bottoms out right around the ending of construction and the beginning of operation,” said Ben Hoen, a research scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Hoen, Eric J. Brunner, Joe Rand and David Schwegman are the authors of “Commercial Wind Turbines and Residential Home Values: New Evidence from the Universe of Land-Based Wind Projects in the United States,” which was published this month in the journal Energy Policy.

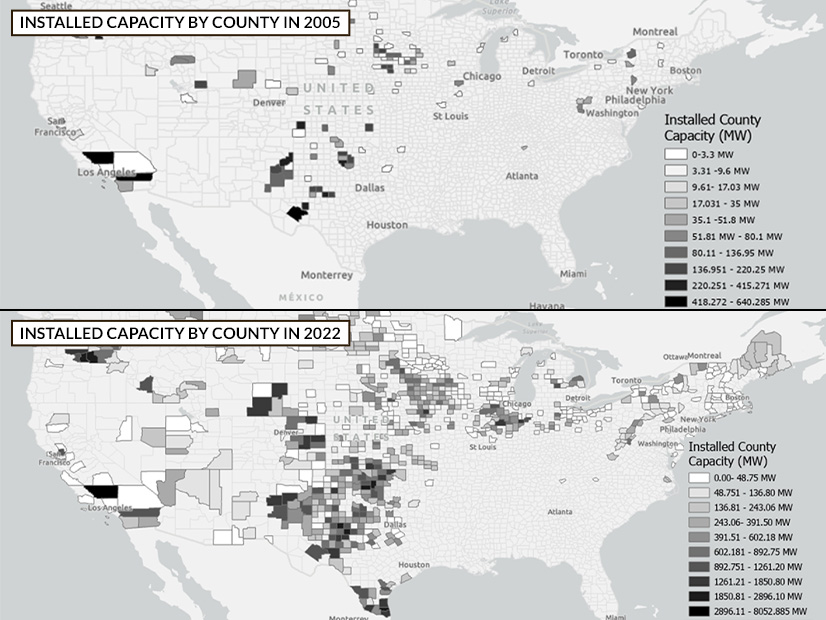

To reach their conclusions, the researchers took CoreLogic’s database of more than 260 million U.S. residential property transactions from 2005 through 2020 and cross-referenced it with the 72,000 towers listed in the U.S. Wind Turbine Database.

After applying a rigorous set of filters and conditions, they were left with 496,000 transactions within five miles of a turbine rated at more than 600 kW; those transactions occurred no more than four years before and 10 years after the turbine was announced.

The greatest price impacts were seen in the 20,331 properties within a mile of a turbine that had been announced or built.

That is vastly more data than some of the previous studies. A 2009 report described by Berkeley at the time as “major” analyzed not quite 7,500 transactions in total.

That study and other studies found no statistically significant impact on sale prices.

But more recent studies in the EU and southern New England did show a negative impact on sale price of houses near wind projects.

“This was a curious finding for us,” Hoen said, “given our past work of not finding statistically significant impacts.”

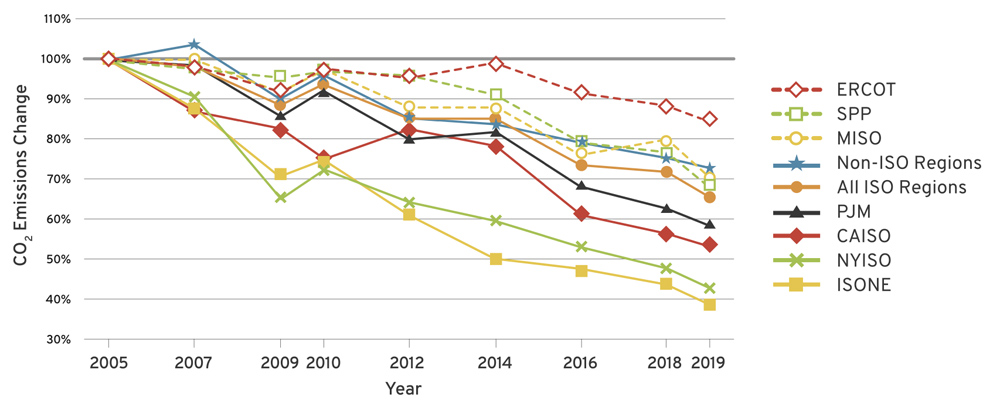

A key factor is Europe is that the population density is much greater than in the United States, the authors said. It is harder to site a wind turbine away from people there. Similarly, the housing price impacts recorded in Massachusetts and Rhode Island were greatest in the more densely populated eastern portions of those states.

Finally, the authors emphasize that in their own analysis for the new study, the greatest price impact was seen in counties that were part of, or adjacent to, metropolitan areas with population greater than 250,000.

Wind power’s impact on home prices is not just a statistical curiosity. It can be a significant factor in building support for a project.

“Property values remain one of the top concerns for local communities that are considering hosting a wind energy project, or have a wind energy project in their midst,” Hoen said. “Often, a home is a family’s most valuable asset, and therefore protecting [it], and protecting its value, is of extreme importance.”

Because a geographically identifiable group of residents has been shown to be impacted economically by wind power projects, it may be possible to directly compensate them, the authors write.

And because the impacts of a project have been shown to begin well before any wind turbines are erected, it may be possible to do a better job explaining the actual impacts of the towering equipment, rather than leave it to speculation. Better line-of-sight photo simulations or location-specific audio simulations might help ease the concerns of nearby residents and the people who buy their homes.

Hoen said the analysis found no variation by size. The largest wind turbines had the same effect on prices as their smaller cousins.

Nor, he said, was there any attempt with this study to analyze the positive impacts of wind power generation, such as job creation or tax revenue.