DUBAI — Hydrocarbons are not going away anytime soon despite growing climate financing and escalating renewables deployment, leaving little chance of reaching the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to 1.5 C, said industry analysts at an S&P Global Commodity Insights event held the day before COP28 officially opens in Dubai.

This year’s Conference of Parties (COP) climate negotiations will illuminate the gap between ambition and action as countries report on how they’re progressing against stated targets in emissions reductions.

“There will be a stock take around where we said the world would be and where the world actually is,” said Saugata Saha, president of S&P Global Commodity Insights. “Our sense is that the stock take is going to show that emissions currently are roughly two times what it needs to be or what it should be to get us to a 1.5-degree scenario by 2100.”

While S&P Global’s analysts were able to force two scenarios that would limit climate change to a 1.5 C rise, no one saw those scenarios as likely to unfold given the massive scope of the change needed and the pace of change to date.

“Fossil fuels have never represented less than 80% of global total primary energy demand since the 1990s, and probably going back many years before that,” said Paul McConnell, executive director of climate and sustainability at S&P Global Commodity Insights.

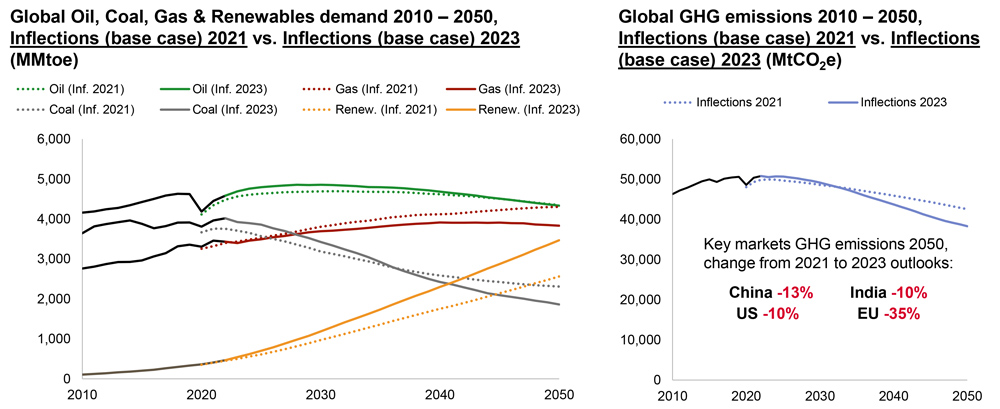

The event coincided with the release of a discussion document, “Energy Transition: Strategic Choices Demonstrating Progress.” S&P Global’s analysis included several scenarios, and its “Base Case” scenario reflects a faster-than-expected decline in demand for fossil fuels as well as an acceleration of renewables deployment. But even with that better-than-expected transition, that scenario still results in 60% of the global primary energy mix coming from fossil fuels by 2050 and a 2.4 C temperature rise by 2100.

“Energy is not the enemy. Emissions are the enemy, and that’s what we need to be thinking about,” Saha said.

Saha suggested paying close attention to how the future of fossil fuels is discussed at COP28. “We anticipate there will be a lot of conversation around ‘phase out’ versus ‘phase down’ and abated versus unabated use of fossil fuels,” he said. “Those will have a meaningful impact on what the next few years look like.”

The phaseout — or lack thereof — of fossil fuels has gained additional attention after the Centre for Climate Reporting and BBC revealed that the president of COP28, Sultan Al Jaber, an oil industry executive, planned to use the climate talks to do oil deals, confirming the fears of climate activists who questioned both the location of COP28 and the industry ties of the talks’ president.

When looking at energy from hydrocarbons, it’s important to distinguish those energy sources based on carbon intensity, he said, citing the sixth edition of Platt’s “Periodic Table of Oil” which maps carbon intensity of the many distillates derived from various grades of crude oil.

Saha noted the wide variances in the carbon intensity of various grades of crude oil, and that “even within a particular grade of crude oil, there can be further significant variances of carbon intensity based on the field of production, the producer, the assets, etc. This is one example where we made a start to assess carbon intensity, provide transparency to the markets and make sure that we are creating the framework for people to make good decisions.”

Beyond the Energy Transition: The Trilemma

Saha said the conversation has changed over the past few years from being focused on the energy transition to looking at solving what he calls the energy trilemma: sustainability, security and affordability. “Balancing these three is no mean feat.”

While energy sustainability is self-explanatory, security — making sure there’s access to energy as and when needed — has taken on new importance.

“Some of the recent geopolitical events over the last three years or so, and some of the supply chain shocks which continue to do this day, amplify the need for energy security as a part of the equation that needs to be solved,” Saha said.

“Energy affordability is equally important. We shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that there are a few billion people who are counting on affordable sources of energy as a means [of] alleviating poverty or getting a few hundred million people onto a path to prosperity,” he said.

Financing the Energy Transition: Some, But Not Enough, Good News

An uptick in energy-transition-related financing indicates the business case is getting more attractive, Saha said.

“Financing is important because A, it makes things happen, and B, it is a very good leading indicator which shows how capital is being deployed to solve problems of tomorrow,” he said. “We know that energy transition-related financing is approaching a $2-trillion-a-year number globally with about half a trillion of that coming from the U.S., and that’s the good news. Part of the bad news is this is a fraction of what is required.”