Earth is living through its hottest year on record, and global efforts to curb human-generated greenhouse gas emissions driving those high temperatures are not keeping up with commitments to cut emissions, which individual countries made under the Paris Agreement signed eight years ago.

New directions, new actions and higher ambitions are urgently needed if the increase in the global average temperature is to be held to the 1.5 degrees Celsius set in Paris.

The opening day of the 28th U.N. Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP28) in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, offered multiple opportunities for speakers to repeat these rallying cries — and put their own spin on what those statements mean and what actions should be taken.

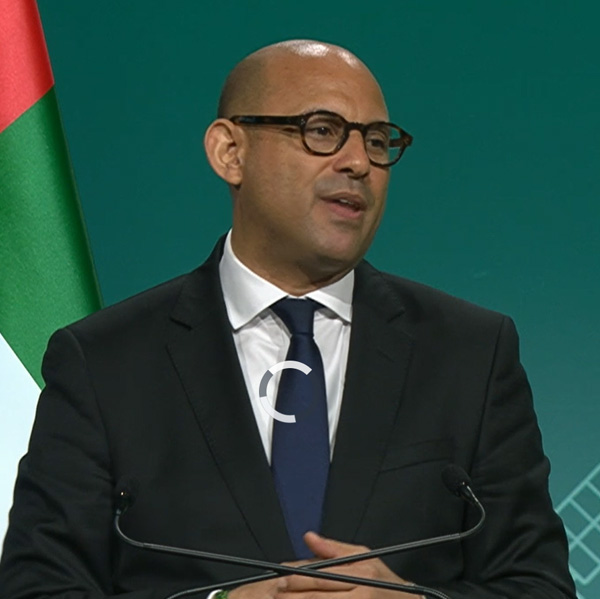

“The world has reached a crossroads,” said Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber, COP28’s president, who is also CEO of UAE’s state-run Abu Dhabi National Oil Co.

“Yes, since Paris we have made some progress, but we also know that the road we have been on will not get us to our destination in time,” al-Jaber said. “The science has spoken loud and clear. It has confirmed that the moment is now to find a new road, the road wide enough for all of us.”

Calling on participants to adopt a different, more flexible mindset, al-Jaber argued for his “bold choice to proactively engage with oil and gas companies,” many of which he said “are committing to zero methane emissions by 2030 for the first time, and many … oil companies have adopted net-zero 2050 targets for the first time.”

“I know there are strong views about the idea of including language for fossil fuels and renewables in the negotiated text,” al-Jaber said, referring to whatever official agreement is hammered out at the end of the conference. “We collectively have the power to do something unprecedented; in fact, we have no choice but to go the very unconventional way. I ask you all to be flexible, find common ground, come forward with solutions.”

Al-Jaber’s strong ties to the fossil fuel industry have been a flashpoint since January, when the UAE named him to lead the conference.

Controversy flared again Nov. 27, when the BBC reported that the UAE was planning to use the conference for business meetings with more than a dozen countries to promote oil sales, citing documents that included specific talking points for each country. At a press conference Nov. 29, also reported by the BBC, al-Jaber denied any knowledge of the talking points or ever using them in COP-related discussions.

Al-Jaber is also one of the leaders of an international drive to have countries at COP28 commit to triple renewable energy capacity and double energy efficiency by 2030.

‘Teach Climate Action to Run’

Expectations for COP28 — and U.S. leadership at the conference — have been mixed.

After bringing the U.S. back into the Paris Agreement early in his term, President Joe Biden is not attending the conference, sending Vice President Kamala Harris in his stead.

But the opening day saw a major success with the approval of a loss and damage fund, to be used to compensate developing countries for damages they have already sustained from extreme weather events made worse by climate change. Developing countries have been pushing for years for this fund, which was initially approved at COP27 last year in Egypt.

Thursday’s vote actually created the fund, and the UAE immediately pledged $100 million, with the EU announcing a pledge of $245.39 million, including $100 million from Germany, according to a report from Reuters. The U.K. will contribute $51 million; the U.S. $17.5 million; and Japan $10 million.

Rachel Cleetus, energy and climate policy director at the Union of Concerned Scientists, called the loss and damage fund “a significant step forward” but still “deeply flawed.” Speaking at a press conference held by the Climate Action Network, a global consortium of nonprofits and community groups, Cleetus said the recommendations approved for the fund “represent richer countries exercising power and getting their way, for example, through ensuring that the fund’s interim host is the World Bank.”

But the centerpiece of the conference will be the first Global Stocktake (GST), an evaluation of countries’ performance on their climate commitments, in preparation for new commitments to be submitted in 2025, as mandated by the Paris Agreement.

The U.N. 2023 Emissions Gap report, released Nov. 20, found that even if all nations deliver on their original commitments under Paris, the average temperature could rise 2.5 to 2.9 C by 2050. Limiting warming to 1.5 C would require a 42% drop in GHG emissions by 2030, the report says.

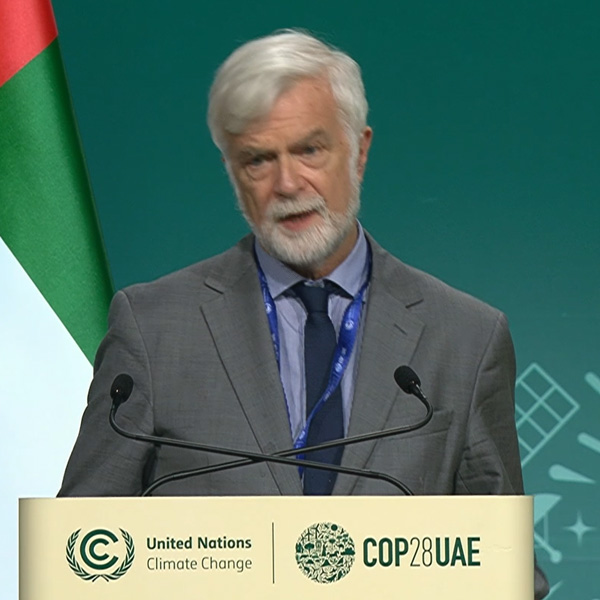

“We are taking baby steps, stepping far too slowly from an unstable world that lacks resilience, to working out the best responses to the complex impacts we are facing,” said Simon Stiell, executive secretary of the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change. “We must teach climate action to run.”

Taking a stronger line on fossil fuels than al-Jaber, Stiell said the GST will provide two options.

“Either we can note the lack of progress, tweak our current best practices and encourage ourselves to do more at some other point in time; or we decide at what point we will have made everyone on the planet safe and resilient,” Stiell said. “We decide to fund this transition properly, including response to loss and damage, and we decide to commit to a new energy system. If we do not signal the terminal decline of the fossil fuel era as we know it, we welcome our own terminal decline, and we choose to pay with people’s lives.”

Following the GST, countries will have to submit transparency reports at the next COP in 2024, ensuring that “the reality of individual progress can’t be concealed,” Stiell said. New, higher commitments for emissions reductions will be due in early 2025, before COP30, where “every single commitment on finance, adaptation and mitigation has to be in line with a 1.5-degree world,” he said.

A Fast, Fair and Full Phaseout

Jim Skea, chair of the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, gave the opening session a short but brutal summary of the current state of global warming and its likely impacts and called for climate action based on science.

“Our planet has warmed by more than 1 degree Celsius since the preindustrial era as the result of burning fossil fuels, deforestation and the unsustainable use of resources,” Skea said. “Human activity has led to changes in the Earth’s climate of a magnitude that are unprecedented over centuries and thousands of years. Climate impacts, some of them irreversible, are widespread, rapid and intensifying, from the poles to the tropics and from the mountains to the oceans.

“Without immediate and deep emission reductions across all sectors, we will not meet the goals of the Paris Agreement,” he said. While options exist for reducing greenhouse gas emissions now, “they need to be scaled up and mainstreamed through policies and increased financing.”

“Ambition levels have to increase fivefold to be able to put us back on track to address this climate crisis,” said Tasneem Essop, executive director of the Climate Action Network. Speaking at the press conference, she called for a just and equitable “phaseout of fossil fuels” while also criticizing the presence and influence of fossil fuel companies at past COPs.

Al-Jaber’s calls for inclusion notwithstanding, a recent report found, for example, that Shell has sent 115 staff members to the annual climate conference over the years.

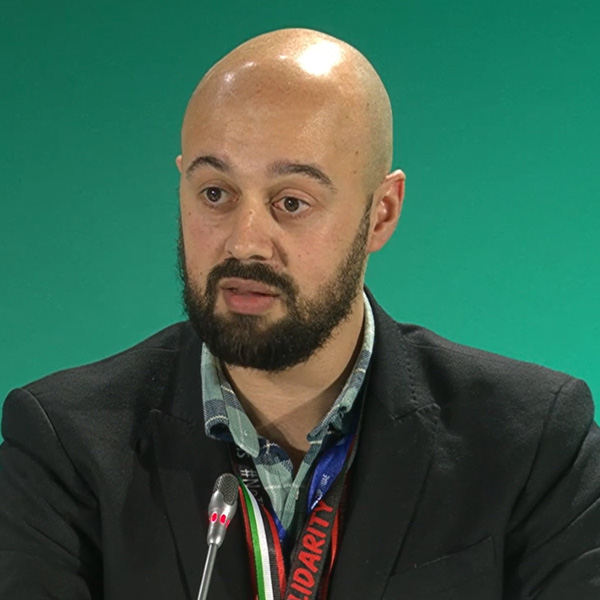

Romain Ioualalen, global policy campaign manager for Oil Change International, a research and advocacy group, said the success of COP28 could rest on “whether it delivers a decision on the phaseout of fossil fuels … which is a fast, fair, full and funded phaseout.”

“That being said, we cannot ask all countries to phase out fossil fuels at the same pace, and in particular rich countries … with diversified economies have a responsibility to phase out fossil fuels first,” he said.