WASHINGTON — The energy transition will require new sources of power as more of the economy is electrified and new investments in information technology are made to help balance the increased loads, speakers said at the GridWise Alliance’s gridCONNEXT conference Dec. 5.

Rep. Bob Latta (R-Ohio) said he always asks how much more power the grid will need in the future when industry representatives come before the House Energy and Commerce Committee on which he sits. Responses vary, Latta said, but he contended that more supply — and particularly baseload resources — are needed to keep vital industries like steel manufacturing running.

“The question always becomes is if you’re going to have to have more power, how do you get there?” Latta said.

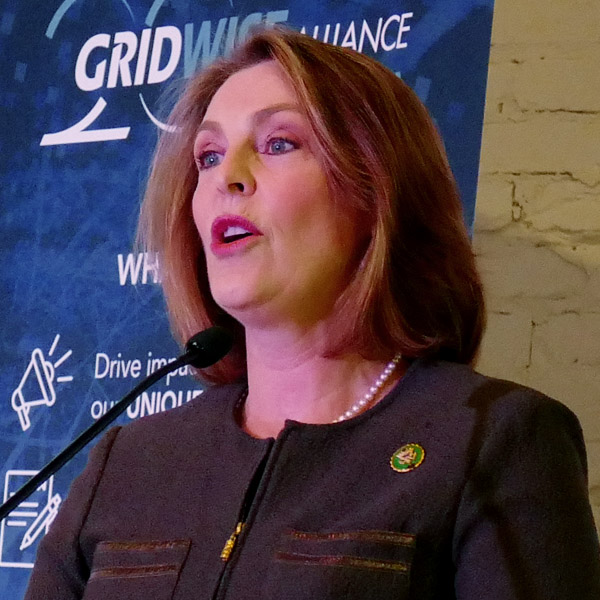

Latta co-chairs the bipartisan Grid Innovation Caucus with Rep. Marilyn Strickland (D-Wash.), and while they might have different visions on the future of the grid, some common ideas help them work across the aisle.

“We don’t snap our fingers and suddenly put in a bunch of charging stations and change how we are providing energy to people,” Strickland said. “We have to make sure that the infrastructure that we have is reliable, that we understand that this is as much about transmission and distribution as anything else, and making sure that we have adequate resources to make these investments.”

Transportation is one of the sectors poised for greater electrification, and while the government offers plenty of subsidies for EVs, charging infrastructure is holding things back, Strickland said.

“Automobile dealers have told us that the United States ranks at the bottom when it comes to EV sales,” she said. “And that’s not because people hate electric vehicle charging stations; we don’t have the infrastructure that makes someone feel as though they can trust how long the charge will last, or that is easily accessible to as many people as possible.”

Taking Risks

The conversations in D.C. and other policymaking circles must eventually get past arguments about whether the energy transition is a good idea, said Gene Rodrigues, assistant secretary for electricity at the U.S. Department of Energy.

“We need to get away from those people who are saying this is a terrible idea and those people saying this is a wonderful idea,” Rodrigues said. “But we need to get to a culture where people are trying to figure out how to make it work.”

Rodrigues said cultural changes around the issue could take a decade. Rep. Kathy Castor (D-Fla.) noted that congressional Republicans have tried to repeal parts of the Investment Reduction Act and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which are heavily funding the clean energy transition.

“We simply don’t have time for that,” Castor said. “Notwithstanding the attempts by the oil and gas industry to take us backwards, the clean energy transition is happening swiftly.”

As the share of energy demand served by electricity grows, so will consumers’ bills, and that is going to require an educational effort from the industry, Exelon Senior Director of Federal Policy Suzanna Mora-Schrader said.

“The affordability piece of this is huge,” she said. “And part of that is not only about us being able to spend money, whether it’s federal dollars, or investment dollars from our rate base, it’s about making customers understand that more and more of their life is a function of electricity. And so, you’ve got to start driving people into understanding share of wallet as opposed to the increase in the bill.”

Part of the transition is going to require utilities taking some risk, something Mora-Schrader said she learned about in previous jobs in less risk-averse industries.

“If you want to do fast, we’re going to have to take some chances,” she added. “And that’s something for utilities to hear and that’s something for our regulators to hear.”

Some of the investments utilities make will have less certainty than others, but they will still need to make them even if the risk cannot be eliminated, Mora-Schrader said.

Maryland Public Service Commissioner Bonnie Suchman pushed back on the notion that regulators will have to embrace more risk.

“I have to recognize reliability,” said Suchman. “We have got to keep the lights on; we have to keep them on now. Recognizing that we have to do [transition-related activities] in five and 10 years, that’s really important.”

But on top of reliability, regulators need to ensure the grid is resilient against extreme weather and that affordability is not lost in the shuffle either, she added.

“A third of Maryland’s residential customers are considered low- or moderate-income. We cannot leave them behind as we continue to deploy these various assets,” Suchman said.

Sharing the Opportunity

One way to ensure the grid is resilient and affordable throughout the energy transition is to make demand more flexible through advanced meters, price signals and participation in markets as FERC Order 2222 contemplates.

“We’re actually seeing transformers failing because of three people plugging in their EV at the same time,” said Mike Phillips, CEO of Sense, a home energy monitor company. “We’re seeing that happen in real time. And there’s two solutions: You either replace all the transformers that can handle these EV loads, or you see that this is happening and you start to make these things intelligent and responsive.”

While some consumption is inflexible, ensuring a car has a full charge for the next day’s commute or the water heater is ready for the morning are not, and both can be controlled given the right technology and policy, he said.

Either utilities or an independent distribution system operator (DSO) will have to coordinate all that activity at the distribution level, ensuring that nodes — or neighborhood circuits — can operate reliably with the new demand, said Curtis Tongue, chief strategy officer at OhmConnect.

“All the devices within that node are able to do their optimization, and the single demand signal is output from that node,” he said. “And then there’s the node-to-node kind of optimization that the DSO or some market operator will be working with,” which would require an interface between the DSO and transmission system operator.

Getting a dynamic system at the edge of the grid to tap into distributed resources can ensure that the utilities do not have to spend so much money that the transition becomes unaffordable, said Chris Irwin, DOE’s transactive energy program manager.

“We cannot accomplish electrification of all loads without a monumental investment in grid infrastructure,” Irwin said. “If the utility is the sole investor in that control surface, we will suffer because of a high price tag. So, as we lift ourselves up, as we lift up grid infrastructure, we must contact those distributed energy resources; we must share the opportunity that exists.”