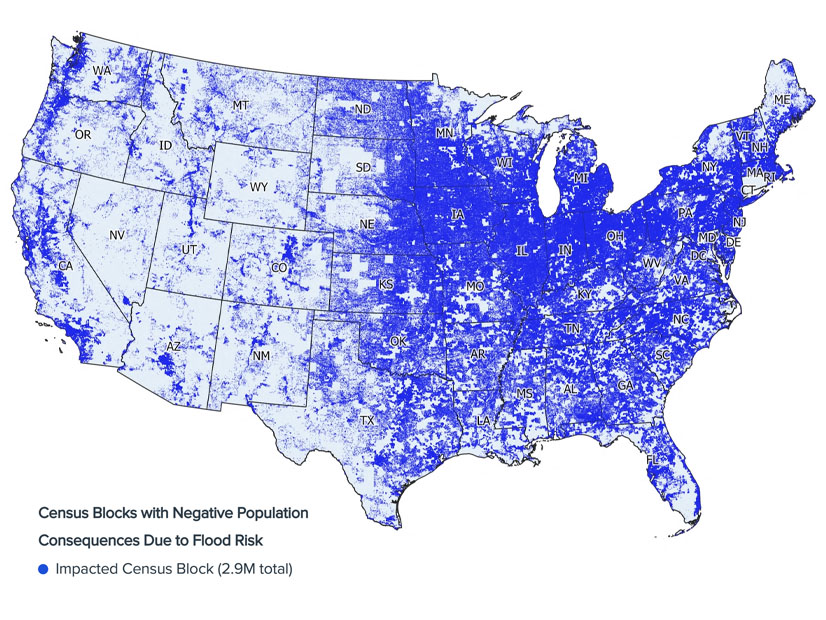

More than 110 million Americans live in places where flood risk is impacting housing choices, and millions have already left or chosen not to move to communities that climate research nonprofit First Street Foundation calls risky-growth and “climate abandonment” areas.

Together, those areas are home to one-third of the population and 42% of all housing stock in the contiguous U.S., and additional areas are expected to reach a tipping point and see similar impacts over the next few decades.

In a Dec. 19 webinar, the authors of the foundation’s Climate Abandonment Areas report published in Nature Communications said the areas experienced a loss of 3.2 million people between 2000 and 2020 that was directly attributable to flood risk. Risky-growth areas, on the other hand, still grew, but at a lower rate than if there were no flood risk.

“More than 34% of the population in the contiguous U.S. live in [census] blocks which have already seen an impact from flood risk on population growth or decline,” said lead author of the study, Evelyn Shu, a senior research analyst at First Street Foundation. “This doesn’t mean that all of these populations declined because of flood risk or even that they will necessarily decline in the future, but a big proportion of the U.S. population is in blocks which may have seen slower growth than they would have otherwise.”

“No matter where you are across the country, models are showing that areas that have high flood risk within a community are not growing as fast or are declining versus places that don’t have that flood risk,” Jeremy Porter, head of climate implications at First Street Foundation, said. The models control for amenities such as schools and medical care, socioeconomic characteristics such as age and income, and economic opportunities such as job availability.

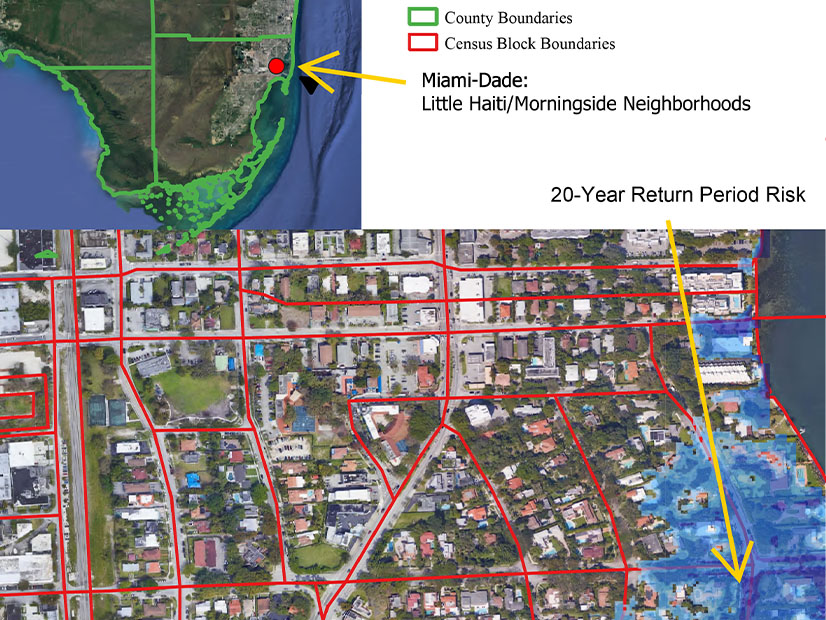

The study mapped high-resolution flood data against granular population changes. Population data was compared for the 11 million census blocks in the contiguous U.S., each with around 80 to 120 people — that is, areas as small as a building in a dense city or a block in a suburban neighborhood.

“We use high-resolution data on historic and current flood exposure, which includes data from the First Street Foundation flood model, and the proportion of properties that are inundated in a given block across the 5-, 20-, 100- and 500-year return periods,” Shu said.

Climate Disasters and Population Mobility

First Street Foundation tracks events resulting in at least $1 billion in damage, including wildfires, droughts, floods, hurricanes and winter storms, and while all states are affected, there are notable concentrations.

“Of the $2.65 trillion in billion-dollar damages that we’ve seen since 1980, over half of it is accounted for by four U.S. states: California, Texas and Florida plus Louisiana. We can see this sort of hyper-concentration of damages and exposure in these areas,” Porter said.

The study focused on flood risk; however, all climate-related risk factors are likely to impact migration within the U.S. The cross-state migration trend that has been going on for decades is dominated by moves “from the Rust Belt to the Sun Belt,” Porter said. “But we’re also seeing information that people are starting to take climate into account.”

While there is interstate migration, they are vastly outweighed by moves within a state or county, and those local moves are where climate risk is layered with personal experience, Porter said.

“You’re starting to take into account things like local knowledge and information about the community that you don’t have when you move across state lines. If I moved in my neighborhood, I know what streets flooded during a heavy rainfall, I know what areas to avoid during coastal flooding,” he said.

Water’s Siren Song

People have a love-hate relationship with water: They are drawn to areas with beaches, rivers and lakes, but there comes a point where the increased flood risk drowns out their siren call. “We tend to see the densest areas, both within cities and across the country, close to water,” Porter said. “As you get more and more properties at risk of flooding within a community, we’re seeing this increase in population until you hit a certain tipping point and then we’re seeing a level-off or even decline.”

While climate abandonment areas had net population declines, risky-growth areas “grew by about 17.4 million people from 2000 to 2020, relatively significant growth for those 2.1 million blocks, but the model showed that they would have grown to about 21.5 million people if it wasn’t for the flood risk,” Porter said. Those areas were so attractive based on amenities, job opportunities and other factors that they outweighed the flood risk for many, but not all, people choosing a community to live in.

People leaving climate abandonment areas often move locally, leading to what some have called climate gentrification. A disproportionate amount of climate abandonment areas are in growing metropolitan areas such as San Antonio, El Paso, Fort Worth and Houston in Texas, and Tucson and Phoenix in Arizona.

“People don’t want to live in those flood-risky neighborhoods, even if they would still want to live in the same area,” Shu said. For example, someone who still wants to live in Miami-Dade County, which has a lot of flood risks, is likely to consider neighborhood differences and make trade-offs, resulting in a migration from the lower-lying areas to higher elevations.

Flood risk isn’t the only thing leading to population loss in climate abandonment areas. Of the 9 million in total population loss in those areas from 2000 to 2020, about 3.2 million could be attributed to flood risk while the other 5.8 million were related to other socioeconomic characteristics of a community, such as lack of opportunity in rural areas. Those areas tend to spiral downwards, with declining housing prices and a loss of local businesses eroding the city tax base and cutting services.