The folks at the U.S. Department of Energy don’t take too many days off.

The day after Christmas, the department released a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on the enforcement of the energy efficiency standards for manufactured housing that it released in May. Those final rules were met — as many of the energy efficiency rules from the Biden administration are — with industry saying they will be too expensive and climate advocates saying they are not rigorous enough.

The NOPR looks to require the home developers to follow enforcement rules already in place from their professional organizations and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Extra documentation may be mandated if potential violations of the regulations are suspected or found.

Reviewing DOE’s record of action ― both hits and misses ― in 2023, the word that comes to mind is “relentless.” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm was ubiquitous, popping up at conferences, research or manufacturing facilities and other events with exuberance at the latest DOE announcements. Department emails flew into reporters’ inboxes multiple times per day, with more NOPRs, requests for information or announcements of new funding opportunities or awards, all aimed at distributing the billions in clean energy funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act.

Keeping up has been daunting but extremely important because Granholm and company have become the leading edge of President Joe Biden’s drive to decarbonize the U.S. power system by 2035 and zero out greenhouse gas emissions economywide by 2050.

The goal, as Under Secretary of Infrastructure David Crane often says, is a U.S. energy transition that is led by the private sector but enabled and accelerated by the government.

Crane and other officials at the department are laser-focused on reshaping the U.S. energy landscape, and they know they may have only another year to score the early wins and build the momentum needed to make any potential Republican rollback unpopular and unlikely.

Clean Energy Manufacturing and Jobs

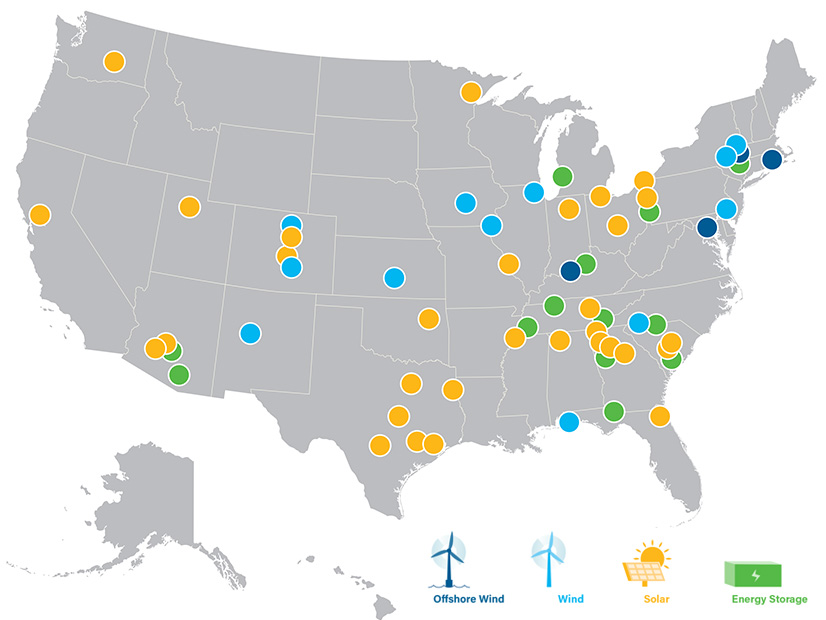

The most immediate and transformational effects of the IRA’s clean energy tax credits have been through the ongoing wave of announcements of new clean energy manufacturing facilities, from solar and wind to energy storage and electric vehicles. In an end-of-the-year press release, DOE noted it had invested $169 million to accelerate the manufacturing of electric heat pumps at 15 sites across the U.S. and another $390 million to build out wind, solar and EV supply chains.

The federal spending has prompted growing amounts of private investment. Tracking clean energy investments since the passage of the IRA in August 2022, the American Clean Power (ACP) Association reports that $408 billion of private sector investments have been announced in 113 new or expanded manufacturing facilities, creating close to 42,000 manufacturing jobs.

Perhaps most significantly, the new investments and jobs are concentrated in the Southeast and Midwest, where Republican lawmakers who opposed the IIJA and IRA now are welcoming the new manufacturing projects.

The Hubs

Red states also received a significant share of awards from the IIJA’s funding for hydrogen and direct air capture (DAC).

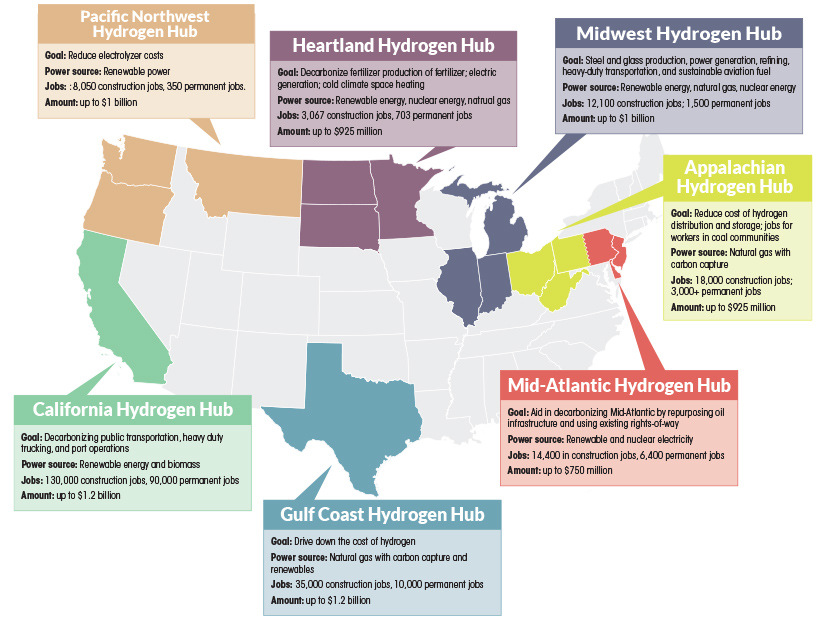

The law’s $7 billion for regional hydrogen hubs sparked fierce competition, with DOE selecting seven hubs to begin negotiations for their share of the money. As set out in the law, the seven hubs announced in October were regionally and technologically diverse. Proposed hubs in California and Texas made the final cut, as did multistate collaborations in the Midwest (Illinois, Indiana and Michigan), the Mid-Atlantic (Delaware, New Jersey and Pennsylvania) and the Pacific Northwest (Montana, Oregon and Washington).

The Appalachian hub in Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia is intended to produce hydrogen using natural gas with carbon capture, and a “Heartland” hub in Minnesota and the Dakotas plans to use a mix of renewables, natural gas and nuclear.

DOE also committed another $1 billion from the IIJA to help build out solid market demand for the clean hydrogen the hubs will produce.

The department announced the first two DAC hubs that will be designed, in Granholm’s words, to “suck decades of old carbon pollution straight out of the sky” to be permanently stored underground or put to industrial or agricultural uses.

The hubs in Texas and Louisiana will receive a total of $1.2 billion in IIJA dollars, and neither plan to use the captured carbon dioxide for enhanced oil recovery — that is, pumping CO2 into low-producing wells to increase their output. Two more hubs will be funded, but DOE has said it may wait on launching the second round to allow a wider range of DAC technologies and business models to be developed.

In another year-end announcement, EPA granted Louisiana primacy over the permitting of wells and CO2 sequestration projects.

Doubling down on DAC, DOE is investing $500 million in IIJA funds to support the buildout of CO2 pipelines and launched a Responsible Carbon Management Initiative to “encourage … the highest levels of safety, environmental stewardship, accountability, community engagement and societal benefits in carbon management projects.”

This initiative reflects the fine line DOE and the Biden administration are attempting to tread on DAC and clean hydrogen. DOE and others have framed these still-emerging technologies as critical to the administration’s climate goals, but environmental groups remain skeptical, seeing them as a hedge for the continued burning of fossil fuels.

Transmission

Like industry in general, DOE is aware that reaching Biden’s goal of decarbonizing the U.S. electric power system by 2035 will not be possible without a major expansion of both intra- and interregional transmission and major changes in the way those lines are planned and financed.

In the department’s first foray into transmission finance, it announced in October that it would sign on as an anchor off-taker for three interstate transmission lines, with a capacity of 3.5 GW. The total investment from the IIJA could be up to $1.3 billion.

The projects again are geographically diverse — in the Southwest, Mountain West and New England — but all would bring renewable energy to areas with high demand and a need for system reliability and resilience.

According to DOE, the projects for the first round of funding from the IIJA’s Transmission Facilitation Program were chosen based on analysis in the 2023 Transmission Needs Study, released along with the funding announcement. The long-awaited study provided regional breakdowns of existing transmission and the intra- and interregional HVDC lines needed to ensure reliability and build up capacity for the power transfers across regions.

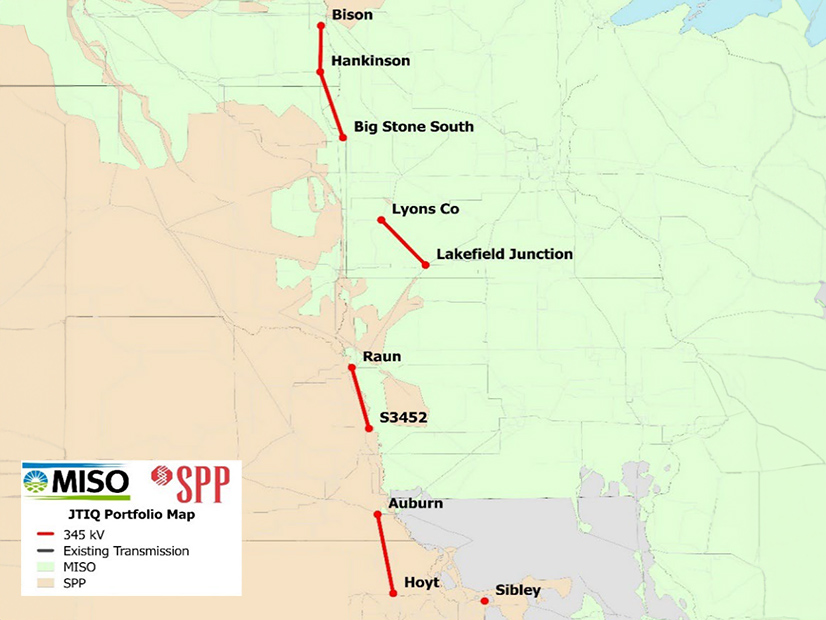

Interregional transmission also got a boost in DOE’s Grid Resilience and Innovation Partnerships (GRIP) program, which awarded $3.46 billion from the IIJA to 58 projects across 44 states. While most of the GRIP projects will be intrastate, the five transmission lines in MISO and SPP’s joint targeted interconnection queue (JTIQ) portfolio got $464 million, the largest of the 58 awards announced.

DOE’s final interregional transmission announcement of the year came Dec. 19, when the department’s Grid Deployment Office released final guidelines for the designation of National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors (NIETCs). The corridors are narrowly defined geographic areas where transmission is urgently needed to ensure power reliability and affordability.

Aimed at speeding up the often decade-long time frame for transmission planning and permitting, NIETC designation would have DOE provide funding for new lines in that area and FERC exercise its “backstop” permitting authority in the event a state denies a permit for a project or delays it for more than a year.

EV Chargers and Tax Credits

DOE also faced some substantial challenges in 2023, which may become more significant as Biden faces low approval ratings during his campaign for re-election.

Specifically, promised consumer savings from the IRA’s tax credits and rebates for EVs and energy efficient home upgrades have been slow to materialize.

With $5 billion in IIJA funds, the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program was aimed at relieving consumer concerns about charging EVs by building out a national network of 500,000 DC fast chargers on U.S. highways. But almost two years on, the first federally funded charging stations only recently opened in Ohio and New York.

The IRA’s tax credits for EVs have been a continuing flashpoint for the administration, with Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) repeatedly slamming the Treasury Department for its interpretation of the law’s domestic content provisions, which he considered too lax. More than 40 models qualified for either the full $7,500 tax credit or half in 2023, but under the latest regulations released in December, any EV with batteries or battery components made in China will not qualify for the credit, cutting down the list of qualifying vehicles to just under 20 models.

The combination of range anxiety and fewer tax credits could put a further damper on automaker and consumer confidence in EVs. Sales, while still healthy, are not growing as fast as expected, and automakers have pulled back investments.

On the upside, 11 states have joined California in adopting the Advanced Clean Cars II rule, according to the Atlas EV Hub. The rule requires that all or a major percentage of new passenger cars for sale in the states be zero-emission vehicles by 2035.

Appliance Wars

The IRA’s $8.5 billion for rebates for home energy-efficiency upgrades have been another point of frustrated expectations. The money, for “whole-home” upgrades and rebates on individual appliances, has gone through a long rollout, with DOE issuing guidelines for states to apply for their share of the money in August — a full year after the law was passed.

The application process for the states to get their allocation of the funds is complicated. The rebates are targeted specifically at low-income households, which means states have to ensure their own processes for income verification meet the federal requirements. Some states will have to hire staff to administer the programs, and the local contractors who will be installing the new appliances and other efficiency upgrades will need extensive training in the new technologies.

In other words, the money will not be reaching consumers and lowering their energy bills this winter.

At the same time, DOE continues to update appliance and building energy efficiency standards, as required by the Energy Conservation and Production Act.

As of Dec. 29, when DOE issued final efficiency standards for residential refrigerators and freezers, the department released a total of 30 proposed or final energy efficiency standards in 2023. The refrigerator standards have the support of industry groups, such as the Association of Home Appliance Manufacturers, which said DOE had done a good job of balancing efficiency improvements with consumer choice.

But the department sparked a political firestorm in February when it released proposed regulations for improving the efficiency of both electric and natural gas stoves, limiting the electricity or natural gas they could use per year. Republican and some Democratic lawmakers railed against the rule, saying it effectively would ban natural gas stoves. At congressional hearings on the matter, some lawmakers compared how long it might take to boil water on electric versus natural gas stoves.

The congressional outcries built on debates at the state level, where the banning of natural gas hookups in new construction has become a flashpoint between local and state governments across the country. At least 24 states have passed laws that prohibit such bans, according to S&P Global.

Responding to the criticism, DOE released a statement “addressing misinformation” on the proposed regulations, which, it said, would not ban gas stoves and noting that the proposed standards would not go into effect until 2027.

Election Year

Politicizing consumer choice has become an effective argument for Republicans, who have leveraged it to win support even among some Democrats. A Save Our Gas Stoves Act (H.R. 1640), prohibiting DOE from enacting any energy efficiency standards on stoves, passed the House in June on a 249-181 vote but stalled out in the Senate.

That bill began life in the House Energy and Commerce Committee, led by Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.), one of the fiercest critics of both DOE and the Biden administration’s energy policies. Speaking on the House floor in support of the bill, McMorris Rodgers called DOE’s proposed regulations a “backdoor” effort by the department and “radical environmentalists” to “control the home appliance market.”

On the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wyo.), the committee’s ranking member, has been equally vitriolic, railing against any perceived misstep by DOE. In one of the year’s confrontations, Barrasso criticized Jigar Shah, director of the Loan Programs Office, for participating in industry events, including dinners, sponsored by the Cleantech Leaders Roundtable (CLR), a group Shah started in 2017.

After Barrasso pushed him to stop attendance at CLR events, the notoriously quotable Shah defended his appearances at a wide range of industry conferences, saying, “I’m more accessible than a ham sandwich.”

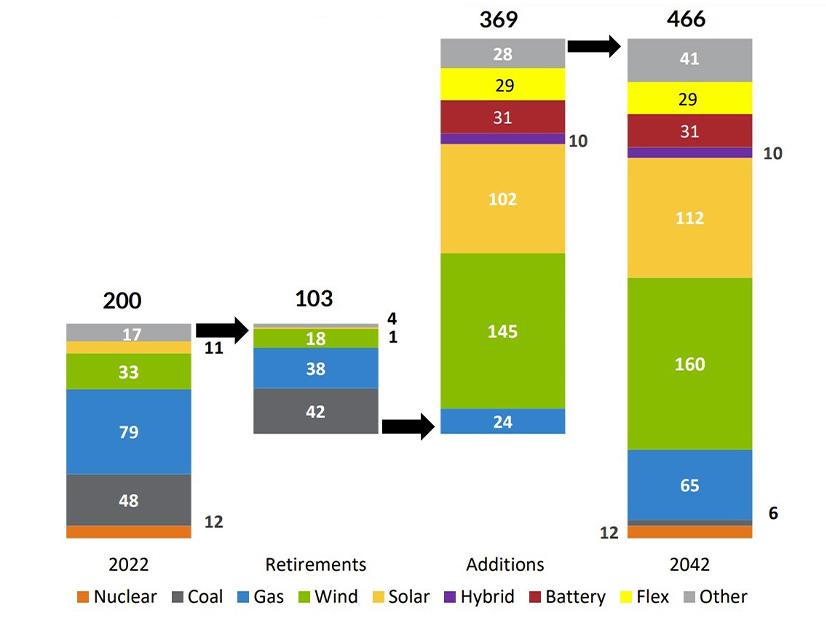

But while Republicans continued to snipe at DOE, Congress mostly declined to act on a critical component of the energy transition: streamlining and accelerating permitting for transmission and the 2,000 GW of solar, wind and storage sitting in interconnection queues across the country.

The permitting provisions in the debt ceiling deal — the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 — set new limits on environmental reviews under the National Environmental Policy Act and requires the reviews to be conducted under a lead agency to avoid repetition of efforts. But the deal left other core issues unresolved, such as if and how litigation of review decisions should be curtailed from the current six-year window.

Whether bipartisan solutions can be found in 2024 remains an open question. A key test may be the Building Integrated Grids With Inter-Regional Energy Supply (BIG WIRES) Act, introduced in September by Sen. John Hickenlooper (D-Colo.) and Rep. Scott Peters (D-Calif.).

The bill would require FERC to ensure that RTOs and ISOs plan and build the interregional transmission that will allow them to transfer 30% of their peak electrical loads to neighboring regions.

What is more likely is the upcoming presidential election will intensify Republican scrutiny of DOE, as well as accelerate the pace of the department’s efforts to distribute federal funds and issue regulations for a range of clean energy and energy efficiency initiatives.

A wild card in the upcoming election is Manchin, who has announced his intention to retire from the Senate and has said he is open to a third-party run. Jennifer Franks, a political consultant, has formed a long-shot political action committee supporting a bipartisan ticket of Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) and Manchin, according to a report in the Deseret News.

Granholm is typically undeterred ― and determined. In a New Year’s Day post on X (formerly Twitter), she said, “We are charged up and ready for another job-creating, clean energy deploying and consumer-savings chapter of [Biden’s] Investing in America agenda.

“Buckle up because it’s going to be another historic year.”