The Department of Energy is preparing to award up to $890 million to three carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) demonstration projects located at existing natural gas- and coal-fired power plants, with the goal of avoiding up to 7.75 million metric tons (MMT) of carbon dioxide emissions per year.

Announced on Dec. 14, the three projects are the first to be selected as part of DOE’s Carbon Capture Demonstration Projects Program, with $1.7 billion from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to fund at least six CCS projects at both power plants and industrial facilities that do not produce power.

According to the funding announcement, originally issued in February, DOE was looking for projects that would provide “transformational domestic, commercial-scale, integrated CCS demonstration … designed to further advance the development, deployment and commercialization of technologies to capture, transport (if required) and store CO2 emissions.”

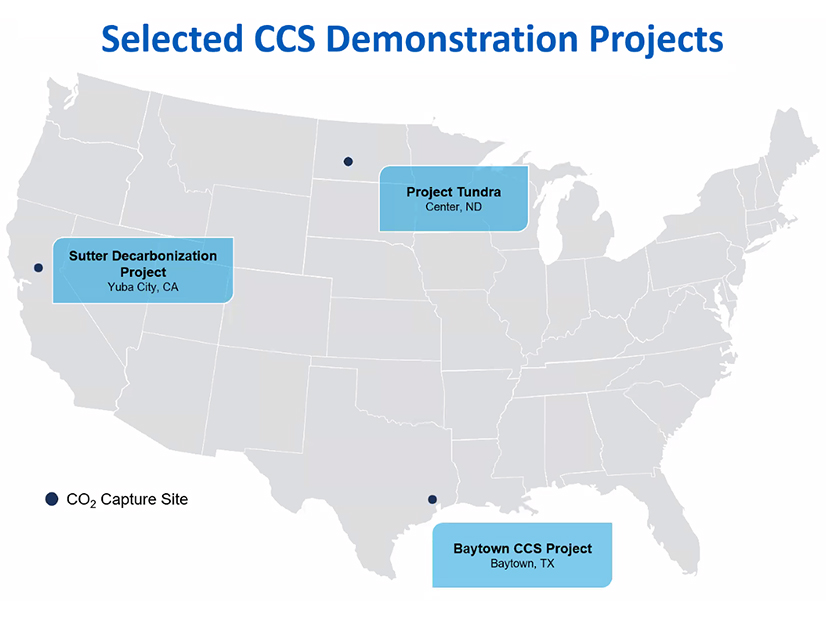

The three projects selected are:

-

- The Baytown Carbon Capture and Storage Project in Baytown, Texas, near Houston, is a natural gas, combined cycle plant, owned by Calpine, and is slated to receive up to $270 million. The CCS technology to be used has been developed by Shell and would sequester the captured CO2 in underwater saline aquifers on the Gulf Coast. The project could use a greywater cooling system that recycles wastewater and would sequester an estimated 2 MMT per year. The primary off-taker for the power produced with CCS would be Covestro, an industrial manufacturer of plastics.

- Project Tundra, located near Center, N.D., near the state capital of Bismarck, would use Mitsubishi CCS technology to capture up to 4 MMT of CO2 at the Minnkota Power Cooperative’s Milton R. Young coal-fired power plant. The CO2 would be stored in “saline geologic formations” sited beneath or near the power plant. The project could receive up to $350 million in federal funds.

- The Sutter Decarbonization Project in Yuba City, Calif., another Calpine natural gas combined cycle plant, would use yet another CCS technology developed by Ion to sequester up to 1.75 MMT of CO2 per year. According to DOE, the project also would be the first in the world to use an air-cooling system, rather than water, responding to “a critical concern of the local community and an imperative to further deployment of CCS in the arid Western U.S.” The pipeline for the project would run within or parallel to an existing natural gas pipeline right of way. Federal funding could be up to $270 million.

None of the CO2 captured by the projects would be used for enhanced oil recovery, in which captured CO2 is pumped back into low-producing oil wells to push out more oil. Awardees are required to provide at least 50% of project costs, according to the funding announcement.

CCS Normalized?

Immediate reactions from awardees and CCS industry groups framed the projects as critical for the U.S. to reach its goals for greenhouse gas emission reductions.

“We’re grateful that the Department of Energy recognizes the importance of developing carbon-capture systems and is positioning the United States to be a leader in the advancement of this critical clean energy technology,” Minnkota CEO Mac McLennan said in a statement. “Innovation is our path forward through the energy transition.” Project Tundra could “help pave the way toward a future where electric grid reliability and environmental stewardship go hand in hand.”

Citing Baytown’s ability to provide firm, dispatchable and “non-duration-limited” power, Caleb Stephenson, Calpine executive vice president of commercial operations, said similar natural gas plants “will be part of our energy infrastructure for the foreseeable future, and now with CCS technology, we can decarbonize them.”

Baytown and the Sutter Decarbonization Project are part of Calpine’s pipeline of 11 CCS projects, according to DOE.

Jessie Stolark, executive director of the Carbon Capture Coalition, hailed DOE’s choice of “geographically diverse projects [that] will demonstrate best-in-class methods to capture carbon at various power generation settings … providing further insight into the continued development and deployment of carbon capture at this critical juncture of climate mitigation.”

Stolark and others point to reports from the International Energy Agency and the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, both of which have said carbon capture will be essential for the world to cut emissions and limit climate change to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

While acknowledging that CCS and other carbon-management technologies are not “a silver bullet” for reducing emissions, Stolark said they should be part of a broader set of solutions and receive “sustained legislative and regulatory support.”

DOE estimates the U.S. will need to capture and sequester between 400 million and 1.8 billion MT of CO2 annually to meet President Joe Biden’s target for economywide net-zero emissions by 2050. But carbon sequestration projects require a special permit from EPA to inject carbon into geologic formations, such as caverns or aquifers needed for permanent storage. As of Dec. 8, EPA is considering 61 applications for these Class VI permits; it has issued only two.

Getting to ‘Go/No-go’

Speaking during an online briefing Dec. 18, Kelly Cummins, acting director of DOE’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED), said that, as is the case with most DOE award selections, CCS projects in this first round of awards are not guaranteed federal funding. Rather, they will begin negotiations with the department for a phased-in release of the money over four planning and development stages, she said.

“During the negotiations process, OCED will discuss how the selectees can make their projects more robust from a technical, financial and community benefit standpoint,” she said. As part of any potential award, “OCED and the project teams will enter into a cooperative agreement, which gives OCED substantial involvement throughout the public-private partnership.”

Between each phase of planning and development, “DOE will assess the project’s progress, and we’ll make a decision about whether the project should receive additional funding. We call this a ‘go/no-go’ review,” she said.

Actual installation and construction of the projects could take three to six years, Cummins said, with ramp-up and operation adding an additional two to four years to timelines. Projects also may have to undergo an environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act.

Each project also must have a community benefits plan that may include labor agreements with unions and training programs and internships for local students. Under Biden’s Justice40 Initiative, 40% of project benefits have to go to low-income, disadvantaged or underserved communities.

The Sutter Decarbonization Project, for example, is negotiating a project labor agreement and has set “a 10% diverse supplier spend goal,” targeting small businesses owned by women and people of color, according to DOE. The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory would serve as an independent third party to monitor the project’s implementation of its community benefits plan.

Next steps will include a series of virtual community information sessions for each project in early January, Cummins said: Project Tundra on Jan. 9, Baytown on Jan. 10 and Sutter Decarbonization on Jan. 11.

A second round of funding is expected “in the future,” Cummins said, to meet the requirements in the IIJA. The law calls for the CCS demonstrations projects to be located at two natural gas-fired plants, two coal-fired plants and two industrial sites.