By Rich Heidorn Jr.

At FERC’s workshop yesterday on uplift and price formation, it was NYISO and MISO that speakers pointed to as the most forward-thinking.

PJM, meanwhile, was a target for criticism from market participants smarting over the $600 million uplift bill from January’s polar vortex.

A FERC staff report released last month said that PJM’s uplift ranked second among organized markets from 2009 to 2013, with charges increasing from about $0.50/MWh to more than $1/MWh over that period. (See FERC: PJM Uplift Ranks High Among RTOs, ISOs.)

Two dozen speakers discussed the causes and impacts of uplift, along with ways to reduce it, during the daylong session. All four FERC commissioners attended at least part of the forum, part of a broad inquiry on price formation that will continue Oct. 28 with a session on offer-price mitigation and offer-price caps (AD14-14).

Asked whether the workshops would lead to a rulemaking, Chairman Cheryl LaFleur said, “We’re keeping an open mind. We don’t have a predetermined next step.”

Robert Weishaar, representing the PJM Industrial and Load Coalition, said FERC “needs to restore public confidence in the existing uplift rules.”

“We still don’t know why we had an extreme blowout in January,” when as much as 22% of PJM’s generators failed to operate. He called for changes to PJM’s force majeure provisions, saying “you could drive a truck through them.”

Uplift Hurts Retailers

Although uplift represented only 1% of PJM’s total cost per MWh in 2013, energy retailers and financial traders said yesterday it has a much larger impact on their businesses.

Peter Fuller, New England director of regulatory and market affairs for NRG Energy, which serves 3 million retail customers, said uplift is “hugely damaging to our efforts to provide pricing predictability.”

Because uplift is not hedgeable, retailers have to estimate the costs, said Elizabeth Whittle, representing the Retail Electric Supply Association. “That works until you have a January 2014 polar vortex.”

In January, PJM had $177 million of uplift for deviations and $387 million for reliability resulting from operators’ conservative operations.

“If you were really good at [minimizing] deviations you could avoid” those charges, Whittle said. But there was no way to avoid reliability charges, she said. “The impact on retail [load-serving entities] was devastating.”

Other Impacts

Mark Smith, vice president of government and regulatory affairs for Calpine, said uplift discourages generation owners from making investments to make their units more flexible, such as reducing minimum run times.

Michael Schnitzer, representing Entergy Nuclear Power Marketing, said that by suppressing LMPs, uplift provides the wrong incentives for demand response and fast-ramping resources. “You’re missing price signals on cold days” that would spur dual-fuel generation and pipeline expansions, he added.

Financial Trader Leaves PJM

Wesley Allen, CEO of Red Wolf Energy Trading, said his small financial trading firm has abandoned the PJM market due to fears that up-to-congestion trades might soon be assessed uplift charges.

FERC last week ordered a review of PJM’s rules regarding UTCs, questioning why they — unlike increment offers and decrement bids — were not being assessed for uplift. (See related story, FERC Orders Review of UTC Rules, page 4.)

Allen, who spoke on behalf of the Financial Marketers Association, said PJM and ISO-NE unfairly charge uplift to virtual trades that don’t cause the problem. NYISO doesn’t charge uplift to virtuals, while CAISO, ERCOT and MISO net their virtuals, essentially eliminating their exposure, Allen said.

Allen compared uplift to a “gas guzzler” tax. In MISO, you get charged the tax if you drive a big sport utility vehicle, Allen said. “In PJM, they don’t care if you ride a bike. They don’t care if you take the bus. Everybody pays.”

Allen said PJM’s uplift charges dwarf the profits on virtuals, which average less than $1/MWh.

While uplift may be small for many, “for virtual traders it’s huge,” Allen said. “There’s just no other way around it.”

Transparency

Allen echoed PJM Market Monitor Joe Bowring’s call for more transparency on the causes and recipients of uplift.

Bowring said transparency could result in market-based solutions in some locations where individual generators receive millions in uplift payments. PJM had 19 generating plants receiving more than $10 million and 33 receiving at least $5 million in 2013, the 33 representing 82% of total uplift for the year.

Bowring has called on PJM to identify the generators receiving uplift, but PJM officials said they are prevented from doing so by confidentiality rules and would require a FERC order giving them approval. (See PJM Won’t Name Uplift Recipients.)

“The fact that we’ve had massive payments to the same units suggests that the market doesn’t know about it or is not reacting,” Bowring said. Transparency “is the only solution we can think of. If it remains secret, the market cannot self-correct.”

John Rohrbach, director of regulatory and market affairs for ACES, said confidentiality was intended to protect competition. “To the extent it is preventing competition from occurring, that is something that should be addressed.”

But David Patton, Market Monitor for NYISO, MISO and ISO-NE, questioned what solutions would result from transparency.

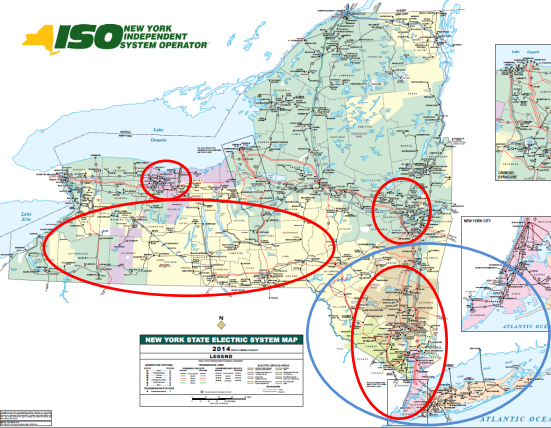

The upper peninsula of Michigan has been a persistent cause of uplift in MISO, he noted. “Everybody sort of knew what was happening. But nobody is going to do anything about it because there’s no product that someone can make a profit off of. You need products and you need pricing. Transparency alone I think will have limited impact.”

Role for RTEP

Bowring also said PJM should consider uplift when developing its Regional Transmission Expansion Plan. “As far as I can tell [uplift fixes] are not incorporated into RTEP,” he said.

Stu Bresler, PJM vice president of market operations, said the RTO can address such issues in the RTEP. He cited the RTO’s decision to add two transformers at the Wylie Ridge substation to eliminate use of Transmission Loading Relief procedures.

Planners “consider these uplift payments even if they’re not captured in LMP,” Bresler said. “It’s another signal that the system is chronically constrained.”

Bowring was not satisfied. “I don’t think it’s being done adequately now,” he said. “It’s not going to solve all uplift, but it can address those persistent problems when there’s a transmission solution.”

Bowring and Bresler also squared off over the issue of closed-loop interfaces, which PJM has begun using in the last year to capture in LMPs operator actions taken to address voltage problems. The RTO has also used them to get sub-zonal demand response to set price, which Bowring called an “inappropriate use of a closed-loop interface.”

Bowring also said the interfaces can have unintended consequences on Financial Transmission Rights funding and virtual bidding.

What other RTOs are doing:

Speakers pointed to NYISO’s “hybrid pricing” as a strategy that has reduced uplift. MISO recently won FERC approval for a new initiative, Extended LMP, which builds on the NYISO model.

Patton said he has recommended that MISO also introduce a local reserve product. RTOs also should change their hourly settlement policies to align them with the five- or 15-minute dispatch procedures, he said.