House Republicans on Jan. 30 lambasted a deal that the Biden administration struck between Oregon, Washington and four tribes on four dams along the Snake River, claiming it will lead to their breaching and threaten power reliability and other industries.

The administration announced the deal in December, and Democrats on the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Energy, Climate and Grid Security argued it would end uncertainty around the four Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) dams, which had been under litigation for decades because of their impact on salmon and other fisheries.

The Columbia River System is the “beating heart” of the Northwest, and removing the four dams would imperil electric reliability in that region and the broader West, committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.) said.

“While the administration will say only Congress has the authority to breach the dams, they wasted no time entering into commitments that bypass Congress and agreeing to spend more than a billion dollars to achieve their political goal, again without congressional approval,” she added. “What’s worse is, despite my repeated calls for transparency, the White House actively and deliberately left out voices of those who depend on the river system the most. Dozens of stakeholders and utility companies practically begged to be heard in this process, only to be turned away, shut out and ignored.”

The Columbia River is home to 13 species of salmon that are endangered, and the tribes who live along it have depended on their annual runs for thousands of years, said subcommittee Ranking Member Diana DeGette (D-Colo.).

“Construction and operation of the dams, private dam building and population growth have negatively impacted wild fish populations,” DeGette said. “This has led to years of litigation and court rulings, which have found operation of the dams violates the Endangered Species Act.”

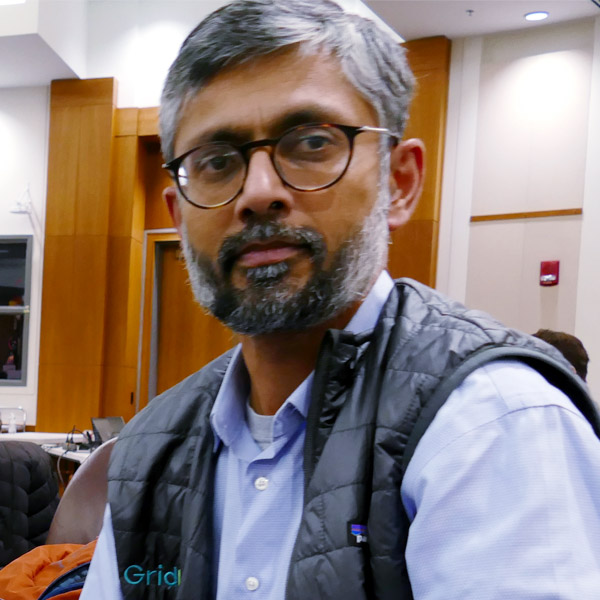

Treaty obligations to the tribes allow them to harvest 50% of the salmon catch; the fish’s declining numbers violated those obligations, said Yakama Nation Tribal Council Member Jeremy Takala. “My people’s tribal treaty rights demand it, as the U.S. Supreme Court recently affirmed treaty fishing rights include the right to actually catch fish, not just to dip our nets in empty waters without salmon.”

Takala was involved in the negotiations on behalf of his tribe that led to the deal, which came out of a recent court case.

“In 2021, a group of plaintiffs filed a motion for the most recent district court litigation seeking to further alter hydropower operations in the basin,” said White House Council on Environmental Quality Chair Brenda Mallory. “The United States government had a choice: defend and face the prospect of another injunction, or work with the plaintiffs and others in the region to find a path forward that could lay the groundwork for an enduring partnership with mutually beneficial solutions. We chose partnership.”

The CEQ convened an interagency group and engaged mediators to facilitate a dialogue with tribes and states in the region, which last fall led to a Presidential Memorandum of Understanding on preserving fish stocks in the region. In December, the White House announced the deal with the “six sovereigns” (the two states and four tribes), which includes more fishery restoration efforts, funding for clean energy development by the tribe and a pause of at least five years in the ongoing litigation, with the possibility of another five.

BPA has been working for decades to improve the environment for salmon and other fish. The deal includes additional funding to improve fisheries over the coming decade, said CEO John Hairston. BPA filed a rate impact statement showing that those additional funds would only add an average of 0.7% to customers’ monthly bills through 2035.

National Rural Electric Cooperative Association CEO Jim Matheson disputed the relatively low cost estimates coming out of BPA.

“If you want to build replacement power when you breach these dams — which I don’t think you can do and have the same comparable resource, by the way — you’re going to spend a lot of money, and it will have a big impact,” Matheson said.

The four dams are also highly complementary to the region’s wind resources because they all have technology that allows them to ramp up and down quickly depending on how hard the wind is blowing, Matheson said.

The agreement filed in court recognizes that Congress must enact legislation to actually breach the dams, but Matheson argued the deal was piling more and more compliance costs on them.

“This settlement effort is a way to force Congress’ hand and put Congress in a position where breaching is more likely,” he said.

Matheson declined to use the word “secret” that was often repeated by Republicans at the hearing about the negotiations, but he did note that just six parties were in the room with the federal government, and so far NRECA and other industry representatives’ letters taking issue with it have not been answered.

The Yakama Nation’s Takala opened his testimony by calling claims about secret negotiations with “radical environmental groups” as claims “fueled by fear and misinformation.”

“This agreement is a historic opportunity to help save our salmon and secure a just and prosperous future for everyone in the Columbia Basin,” Takala said. “First, for clarity, the Yakama Nation is not a radical environmental special interest group.”

Its rights to salmon from the rivers are guaranteed by the treaty the tribe signed with the federal government in 1855, he added.

“Since time immemorial, the strength of our Yakama Nation and its people have come from the Nch’í-Wána — ‘the big river,’ or the Columbia River — and its tributaries and from the fish, game, roots and berries nourished by their waters,” Takala said.