WASHINGTON — EPA still wants U.S. automakers to cut greenhouse gas emissions from their light-duty vehicles almost in half by 2032, but the agency’s final rule released March 20 aims to give the industry more time and flexibility on how to reach that ambitious target compared to the proposed rule issued in May.

Whereas the proposed rule predicted electric vehicles would comprise 67% of new car sales by 2032, the final rule sees a broader mix, with about 56% EVs and 13% plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), according to a senior administration official speaking on background. The rule covers the model years 2027 to 2032.

In addition to light-duty vehicles (LDVs) — passenger cars, SUVs and light trucks — the rule also calls for a 44% reduction in emissions from medium-duty vehicles (MDVs), defined as delivery trucks and vans weighing between 8,501 and 14,000 lbs.

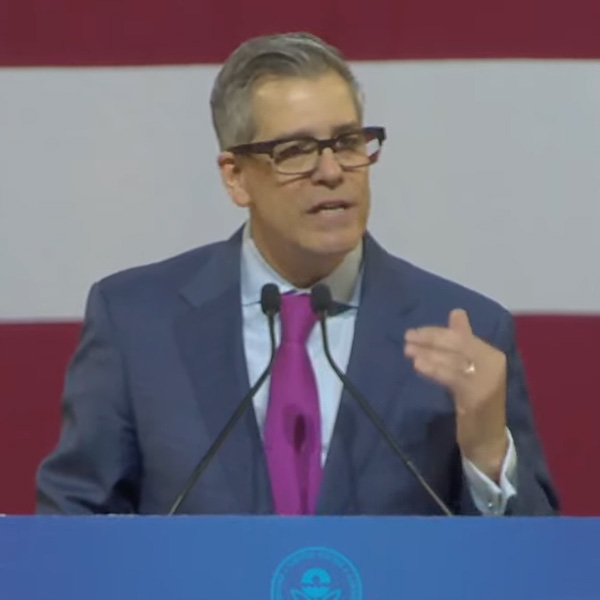

At a rollout event in D.C., EPA Administrator Michael Regan hailed the final rule as “the strongest vehicle pollution technology standard ever finalized in the United States,” targeting GHG emissions of 85 g ― just under a fifth of a pound ― per gallon for LDVs by 2032.

“This technology-neutral and performance-based standard gives the auto industry the flexibility to choose the combination of pollution control technologies best suited to their customers,” Regan said. “Whether it is battery electric, plug-in hybrid, advanced hybrid or cleaner gasoline vehicles, we understand that consumer choice is paramount.”

EPA’s current LDV standard for 2026 is 168 g/gallon, edging up to 170 g/gallon in 2027 before tapering off to 85 g/gallon by 2032 ― a decrease of 17 g/gallon per year. The 2032 target for MDVs is 274 g/gallon, down from 461 g/gallon in 2027.

The “multipollutant emission standards” also will result in a 95% decrease in tiny particulate matter, commonly referred to as PM2.5, which has been linked to heart and lung disease, according to EPA. Nitrogen oxides and other pollutants are expected to drop 75%.

Promoting the final rule, Regan, President Joe Biden and other administration officials have repeatedly said major cuts in vehicle emissions will not mean higher costs for consumers, lost jobs in the auto industry or snowballing effects on the economy in general.

“These technology standards … will avoid more than 7 billion tons of carbon pollution,” Regan said. “That’s four times the total carbon pollution from the entire transportation sector in the year 2021.”

Those reductions will translate to “fewer hospital visits and premature deaths … fewer illnesses like lung cancer and heart disease,” he said.

In a statement from the White House, Biden said the new rule would allow the U.S. to meet his “ambitious target that half of all new cars and trucks sold in 2030 would be zero-emission … and race forward in the years ahead.”

Citing the billions of dollars in private investments announced for new EV and EV battery manufacturing plants ― buoyed by tax incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act ― Biden said the U.S. “will lead the world in autos, making clean cars and trucks, each stamped ‘Made in America.’”

National Climate Advisor Ali Zaidi also stressed the benefits for workers, consumers and the economy. “On factory floors across the nation, our autoworkers are making cars and trucks that give American drivers a choice — a way to get from Point A to Point B without having to fuel up at a gas station. From plug-in hybrids to fuel cells to fully electric, drivers have more choices today. Since 2021, sales of these vehicles have quadrupled, and prices continue to come down.”

Zaidi noted that U.S. drivers now can choose from more than 100 EV and PHEV models.

EPA estimates reduced emissions will generate $99 billion per year of economywide benefits, including $13 billion in public health savings from improved air quality and $62 billion in lower fuel, maintenance and repair costs for consumers. The average savings for individual consumers buying EVs are estimated at $6,000 over the life of the vehicle.

Not a Rollback

When released in April 2023, the proposed rule triggered immediate pushback from many in the auto industry, mostly based on its call for a sharp ramp-up in EV sales beginning in 2027.

With EV sales not increasing as fast as some automakers had predicted, the industry has been pumping the brakes on how quickly it will get new EV models to market.

During a recent earnings call, General Motors CEO Mary Barra said her company is targeting 200,000 to 300,000 EV sales for 2024 and is considering introducing a PHEV model for certain markets, all depending on consumer demand. GM’s last PHEV, the Chevy Volt, was discontinued in 2019.

Administration officials, however, framed the changes to the final rule not as a rollback resulting from industry pressure, but as a way to make the rule more robust and durable. The fast increase of EV sales envisioned in the proposed rule had been based primarily on computer models, a senior official said. The final rule leverages data from automakers and dealers, which indicated the same result in emission reductions could be achieved if the industry had a longer lead time and more flexibility in the mix of vehicles that automakers would produce.

It also takes into account increased efficiency and lower emissions resulting from technological advances in gas-powered cars.

The more industry-friendly rule didn’t pass muster with Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wyo.), who criticized the rule and the Biden administration as out of touch and “trying to force Americans into expensive electric vehicles they don’t want, don’t need and can’t afford.”

“Republicans will fight to overturn the Biden car mandate and put Americans back in the driver’s seat,” Barrasso said.

Speaking in D.C., John Bozzella, president and CEO of the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, was more conciliatory, acknowledging he had been a thorn in the administration’s side for months, advocating for changes in the rule.

“Automakers are committed to electrification, and we want this transformation to EVs … to succeed over the long haul,” he said. “The reason we had strong views on the feasibility of the original proposal and what it required in terms of EV sales is because we know the challenges of [a] choppy EV sales market, public charging still coming online, new supply chains that must be built, all while preserving a customer’s ability to choose the vehicle that works for them and their families. …

“Our message was not whether this can be done ― it can ― but how fast can and should it be done,” he said.

Albert Gore III, executive director of the Zero Emission Transportation Association, noted that the best-selling car in the world in 2023 was electric, Tesla’s Model Y. Tesla also claimed the top four spots on Cars.com’s American-Made Index, with its models Y, 3, X and S.

“We have everything we need today in terms of technology and know-how to meet and exceed this standard,” Gore said. “And if all the manufacturers [at the event] dedicate themselves to meeting and exceeding these goals, like America always does, we will firmly secure our future in a position of global leadership.”

The PEF Calculation

Getting a jump on EPA, the Department of Energy on March 19 also released a final rule on the petroleum equivalent fuel (PEF) calculation, which is a measure of the “fuel efficiency” of EVs; that is, the amount of petroleum-based fuel needed to produce the same amount of energy an EV uses

How the PEF is calculated is important — and political — because it is used by EPA in determining automakers’ compliance with the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards — the federal fuel efficiency levels for automakers. The calculation first was set in the 1980s and has been reviewed periodically, most recently in 2000.

In 2021, the Sierra Club and the Natural Resources Defense Council petitioned DOE to update the two-decade-old calculation. “By overstating the miles per gallon equivalent of any EVs in automakers’ fleets, the prior calculation enabled automakers to continue to sell far more [gas powered vehicles],” the Natural Resources Defense Council said in a press release welcoming the new calculation.

“The old calculation included a multiplier of nearly seven that significantly inflated the calculated fuel economy of electric vehicles. DOE’s final rule phases out the multiplier while updating other data used in the calculation with more current figures,” NRDC said.

The Sierra Club noted that the PEF calculation “is wholly separate and has no impact on compliance” with EPA’s final vehicle emissions standards.

The updated PEF calculation is based on a complicated formula taking into account factors such as average electricity generation and transmission efficiency and average petroleum refining and distribution efficiency.

The PEF is measured in watts-hours per gallon. The current standard, 82,049 Wh/gallon, will be in effect through the end of 2026. DOE’s final rule ramps down the PEF to 79,989 Wh/gallon in 2027 and bottoms out at 28,996 Wh/gallon in 2030 and beyond.