The U.S. needs to take action beyond incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act if it wants to create a truly domestic solar manufacturing industry, according to a report released by the Solar Energy Manufacturers for America (SEMA) Coalition on March 20.

SEMA’s members produce solar panels and their components in the U.S.; they include firms such as First Solar, Q-Cells and REC Silicon. The organization hired Guidehouse Insights to produce the report, “Inflection Point: The State of US PV Solar Manufacturing & What’s Next.”

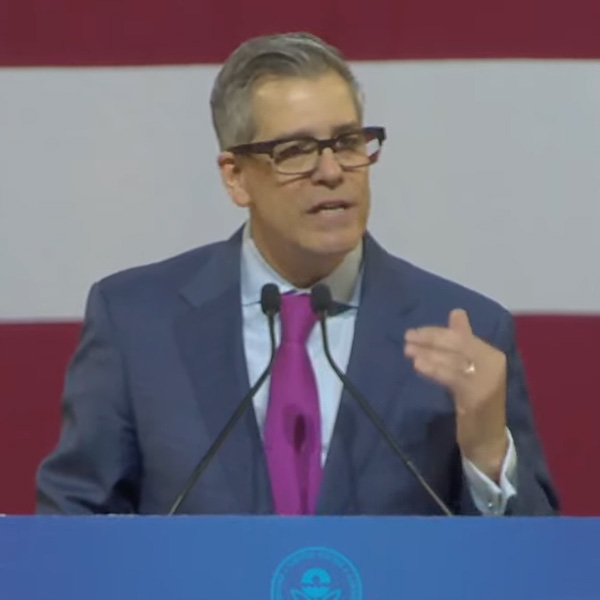

The IRA generated a lot of excitement about increasing the domestic share of the solar supply chain, with policies such as a 10% bonus to the investment tax credit for using domestic panels, but the country’s competitors have responded, SEMA Executive Director Mike Carr said on a webinar.

“Without a U.S. policy response to the current influx of imports in both components and finished products, resulting in significant oversupply, recent factory announcements will likely not come to fruition,” the report said. “While the groundwork has recently been laid for a strong domestic solar manufacturing ecosystem, significant gaps remain and present a threat to its long-term viability.”

Solar has gotten cheap enough that utility-scale capacity should make up about 40% of all generation installed this year, and that share could grow to 60% over the next decade, the report said. Higher prices from higher tariffs and other policies incentivizing domestic consumption would not be enough to derail that, SEMA argued.

“This steady state of deployment is really kind of disconnected from the module prices,” Carr said. “Those have bounced around a fair amount in recent years, including hitting new lows this year, and it really doesn’t affect the trajectory one way or another.”

The effective duty rate on imported solar has dropped from 9.6% in 2021 to just 0.4% last year, but even a ban on imports would not be a boon for domestic manufacturing, as this year’s demand is vastly outweighed by supply because of stockpiling, said Guidehouse Senior Research Analyst Peter Marrin.

“Even if these imports stopped today, we still have a huge problem. … We have about 2.4 to 2.7 times the amount of module supply relative to demand,” he said. “So, we’re that overstocked.”

Solar photovoltaic panels’ supply chain starts out with turning mined quartz into high-quality polysilicon; pulling that into ingots; slicing wafers from the ingots; producing PV cells; and then assembling the module. China dominates the global manufacturing of all those steps, but its share is highest in ingot and wafer production.

“The U.S. currently could produce enough polysilicon to make about 20 GW of crystalline silicon products each year, but the country lacks critical next-step manufacturing facilities for the various refinement and component fabrication steps in the solar cell manufacturing process,” the report said. “The U.S. also lacks capacity to manufacture ingots, wafers and cells, and therefore is entirely dependent on global suppliers for these components.”

A decade ago, the U.S. had nearly a dozen facilities involved in ingot and wafer production that each could produce up to 500 MW annually, but those since have shuttered and now those highest-cost parts of the manufacturing process are the least subsidized by the IRA, the report noted.

“As a direct result of IRA provisions, the U.S. is seeing a significant increase in announced cell manufacturing and module assembly capacity,” the report said. “If even half of this announced capacity comes online, the U.S. could produce enough cells and modules to meet nearly 100% of its new solar demand through 2027.”

Those domestically produced panels and modules still would rely on Chinese wafers and polysilicon, leaving the industry vulnerable to price shocks and possible disruptions from geopolitical disputes.

“Domestically produced solar modules can be roughly 30 to 50% more expensive to produce than imported ones, but various provisions in the IRA aim to reduce this gap by promoting economies of scale and vertical integration,” the report said. “Focusing investments on developing the cutting-edge equipment, knowledge and workforce needed for a strong domestic supply chain can further reduce these costs in time.”

Beyond tariffs and enforcing anti-dumping trade laws, policymakers can move the ball forward by setting stronger standards for bonus tax credits and using federal procurements to induce demand for domestic production, the report said. The 10% bonus tax credit has not been implemented ideally, Carr said, and the Biden administration has seemed receptive reviewing it.

“More than more than half of the value of the module can be produced outside of the United States, and you can still have your module considered domestic,” Carr said. “And we think … that is not really a recipe for success.”