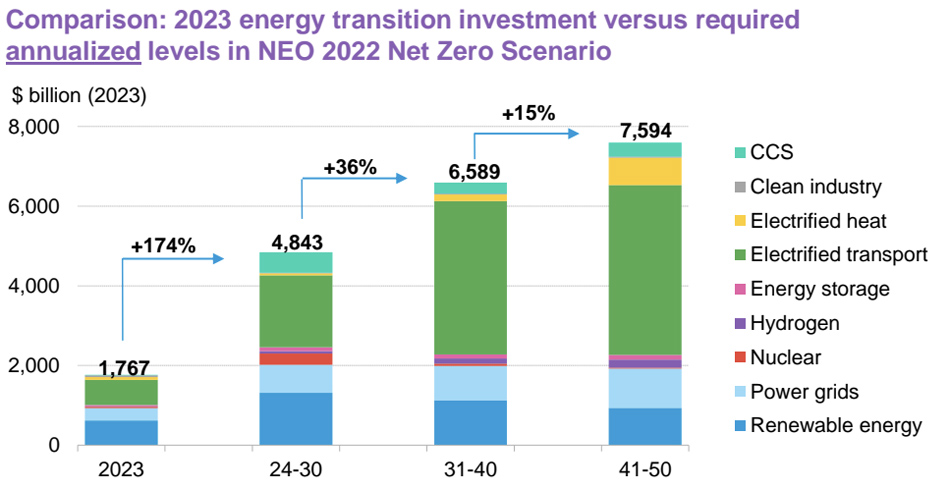

NEW YORK — Global investment in the energy transition grew 17% to more than $1.7 trillion in 2023 — a new high, BloombergNEF CEO Jon Moore told a standing-room-only audience at the opening session of the BNEF Summit on April 16.

Unfortunately, those topline figures aren’t “where we need to be,” Moore said.

“We need to be two-and-a-half times that number, so we need to be investing more on an annual basis than we are today, and that goes up to $6.5 [trillion] and $7.5 trillion in the subsequent decades,” the 2030s and 2040s, respectively, he said. “So, we really do need big numbers here.”

Finding new ways to get more investors to put more of their money into clean energy technologies — especially the startups providing new solutions to critical challenges — was a major focus of the two-day BNEF Summit. Moore’s opening remarks provided a high-level perspective on the transition, which, at present, is moving both fast and slow, he said.

Following Moore, David Crane, under secretary for infrastructure at the Department of Energy, drilled down into how looming predictions for demand growth could affect the existing momentum and financing of the transition.

Among sectors moving fast, Moore noted the lion’s share of new investment is streaming toward renewable energy, electric transportation and power grids, a category that has taken off in the past four years. Global investment in passenger electric vehicles (EVs) was up 36% in 2023, investment in energy storage jumped 77%, and investment in carbon capture and storage (CCS) nearly doubled, Moore said.

Europe — specifically the Netherlands — is the main driver in CCS, with its Porthos project to store carbon dioxide emissions from oil and gas plants in depleted gas wells more than 1.8 miles down in the North Sea. Moore also zeroed in on global investments in solar, where he said “there is now enough [projected] solar capacity to support us where we need to be at net zero at 2030. … So we actually don’t need any more,” though installations will continue at a slower pace.

Investments in battery factories are also running ahead of projected demand, though not to the same extent as solar, he said.

But Moore also cautioned that exponential increases in global investment will be needed for some technologies. While investment in renewables, storage, the grid and EVs will need to increase two to three times by 2030, investment in hydrogen must jump sixfold, nuclear almost ninefold and CCS a whopping 45-fold.

Overall, he said, investment in clean energy supply is close to but has yet to surpass fossil fuel investments. In 2023, clean power supplies drew in $1,023 billion versus $1,098 billion for fossil fuels.

Looking at the global stock taking at the United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties in the United Arab Emirates last year, BNEF is ranking climate progress overall at 3.8 out of 10, Moore said.

“If you added up all the [nationally determined contributions] and everyone achieved what they said they wanted to achieve by 2030, we would reduce CO2 emissions by 5.3%,” he said, well below what will be needed to limit climate change to the 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius set in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

The uncertainty surrounding the U.S. presidential election in November — and its impact on U.S. energy and climate policies — could be multiplied by upcoming elections in other countries, Moore said. India’s seven-phase parliamentary elections kick off on April 19 and continue through June 1.

Countries representing “two-thirds of global GDP” will have elections this year, he said.

‘Bursting at the Seams’

In the U.S., unprecedented federal investments in clean energy provided by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act have slammed into concerns about unprecedented demand growth, Crane said in an on-stage conversation with Thomas Rowlands-Rees, BNEF head of North America research.

“Our world is now bursting at the seams,” Crane said. From 2012 to 2022, demand growth was mostly flat and steady at about 0.5% per year, he said, but now “people are talking about 5 or 6% per year. … In the energy world, those are big numbers.”

The result is that “we’re solving for two different demand problems simultaneously,” Crane said: incremental demand growth from electrification of buildings and transportation, and the “big chunks” of new demand from data centers.

“With this data center thing, and the high-tech companies that are driving that, we need them to become energy companies because they have so many ways they could work with us,” he said.

Many of the projects Crane oversees at DOE, such as the hydrogen and carbon capture hubs, were intended to get first-of-a-kind projects online in the 2020s, to be followed by commercialization and scaling to help reach President Joe Biden’s goal of a decarbonized grid by 2035, he said.

“But this demand [growth] thing seems to be a 2025-to-2030 thing, so we have to look at what we can do in a short period,” Crane said. He pointed to the new Pathways to Commercial Liftoff report on the deployment of innovative grid technologies like advanced conductors and dynamic line ratings, released April 16. (See DOE Report Highlights Benefits of Advanced Grid Technologies.)

Such technologies are “cheaper [and] faster, and we can get somewhere between 20 and 100 GW more capacity on [an existing] system,” he said.

Crane sees a twofold challenge for wide deployment of grid-enhancing technologies: a lack of easily identifiable incumbents in the sector and the need for creative financing.

A decade ago, he said, “I’m looking at something like electric vehicle charging, and there are at least three big incumbent stakeholder groups” — oil companies, utilities and automakers,

“But suddenly, [with] these things like reconductoring, virtual power plants in particular, it’s harder to see who are the natural incumbents that should want to lean into that space, and so it leaves an opening for the more entrepreneurial companies, and we need to support those companies,” he said.

For creative financing, Crane called on the clean energy professionals at the conference to help develop the new approaches to investment that will be needed to get these technologies widely deployed. Upgrading transmission systems usually occurs within “an integrated utility system, so standalone financing of these things is an area for people in this room to pioneer. This is a business opportunity … and we need it.”

“The key partner at the table in this is the financial community that can find ways to get these things done,” he said.